Blast From the Past: The Fix

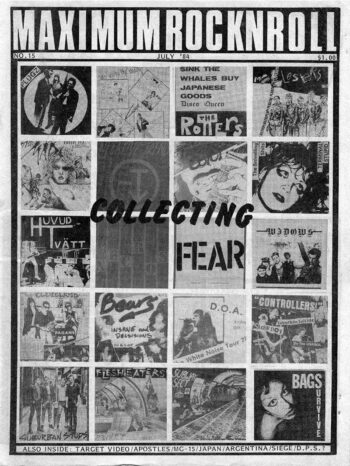

This originally ran in MRR #319/Dec 09 which you can grab hereCan’t Fix This: The Brutal Urgency of The Fix

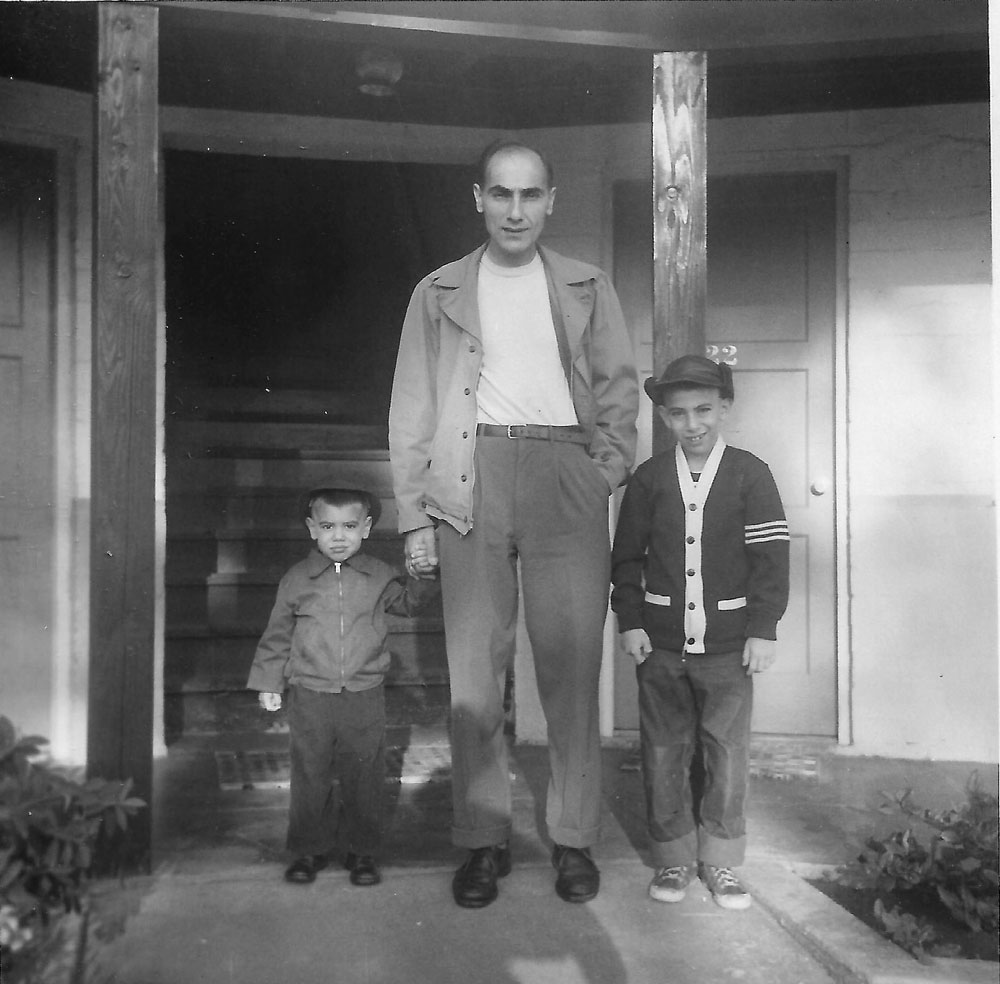

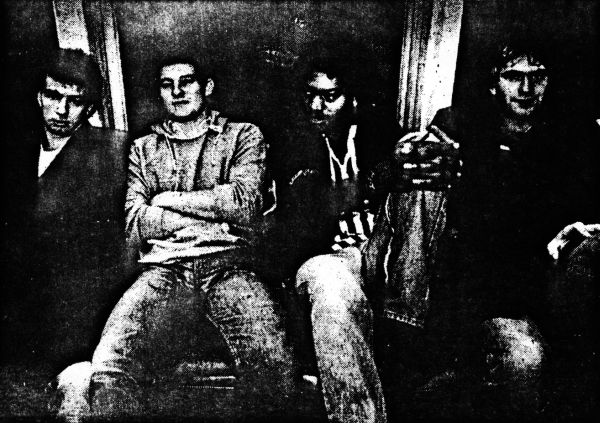

Hailing from Lansing, MI, a college town full of copycat, run-of-the-mill, faceless rock bands, The Fix were a blunt concoction of raw power stolen from the “Gimme Some Skin” era Iggy and Stooges and the dirty Midwest diatribes of the Dead Boys squeezed into ferocious two minute songs at dizzying speeds. In 2006, Touch and Go re-issued their long lost singles Vengeance and Jan’s Room (both released in 1981), along with demos and live tracks, to the hurrahs of hardcore enthusiasts. This interview with singer Steve Miller, who is now a journalist, took place in September in Houston, Texas by David Ensminger.

MRR: Did you see the Fix as carrying forth the legacy of proto-punks like the MC5 and Stooges?

Anytime you grow up in a place like Michigan, it’s just part of your life. You’re used to being weaned on bands like the Stooges and the MC5, so it’s more cultural than it was musical. If you are going to play music, it’s probably gonna have an element of that stripped down, unpolished feel to it. Plus, you’re going to shows. In a lot of areas, people had to wait for the Ramones to come through to really start the bands. The saying was, the Ramones would play a town, leave, and five bands would spring up in the next few months. It seemed like in Michigan we had been going to see shows at these raw-ass places since we were kids, so when you did get around finally to starting a band, it was part of your spirit — that raw edged, beat the shit out of your instrument kind of thing. So, it was really pretty natural.

MRR: Were those people around at all still?

When, we started, it was about 1980, so yeah, Destroy All Monsters (Ron Asheton) was playing around, I believe the bassist from the MC5, Michael Davis, was in that for a time. So, you’d see these guys. Obviously, they were sort of heroes to us since we were little kids, so we might say something, but it wasn’t like you were going to go, “Dude, you were sweet in the MC5″ or something like that. You’d just see them and say, hey, that’s the dude from the MC5. I remember doing a show in Ann Arbor and seeing Ron Asheton there. Everybody knew him. We wouldn’t talk to them much.

MRR: Did you travel much to see shows?

We lived in Lansing. When I was a kid, we traveled to Detroit all the time There was the Masonic Theatre, the Ford Auditorium, and earlier on the Michigan Palace. I remember seeing T. Rex and ZZ Top at the Michigan Palace during the Fall of 1974. We showed up, and we saw T. Rex open. We were all there for T. Rex, and ZZ Top came out, and they had cowboy hats on, and we were like, “Fuck You.” We left. That was the kind of shit we were up to. But yeah, you’d go see Blue Oyster Cult in a small place half-full. All that raw shit would come through. So, we traveled all the time. But by 1980, not so much, because a lot of that arena rock shit was pretty dead.

MRR: Do you remember any leftover student radicalism during that time?

Nah. We were getting into that 1980s kind of thing. Two of the guys in the Fix were students. Craig was the kind who would spout a slogan once in a while. We’d all look at each other and say, “What the fuck did he just say?”

MRR: Did you play music before the Fix?

No, no. Not at all. Mike, the bass player and I, were longtime friends and roommates. We’d known each other in high school. There was a bass guitar lying around. I learned how to play that, but he was better than me on it. Wait. I guess there was a guitar: we might have had one. But we knew there was music to be played, but again, it was a long time. There were catalysts, but there weren’t. It was just like everything coming together, like saying, “Maybe we should play in a band.”

MRR: Then you put an advert up for a singer?

Yeah, we put an ad in a laundromat. It’s like, why? I don’t know why we put it in the laundromat. I guess it was a laundromat that everyone went to. I guess you call them washeterias down here (in Texas). But we put something up, I guess. I think we only had one call. That was Craig.

MRR: And was race ever an issue? Did you have any second thoughts when a black guy showed up?

No, it was so funny. He called and was talking. He would talk a mile a minute. He could talk a good game. He was talking about all his influences and shit, then he goes, as an afterthought, “I’m black too. I don’t know if that helps with our marketing or image or anything.” I was like, “That’s cool man, that’s fine. Let’s get together.” So, he came over, and he was so good on guitar, and he brought two great joints. We smoked those and talked about playing and that was it.

MRR: How segregated was Detroit when you were growing up?

I don’t know. We were never conscious of it. When we would go to concerts, we’d see black folks and white folks. I never saw it as being a big issue.

MRR: Did you go see bands like Funkadelic?

No, but I remember one time Aerosmith and Funkadelic played at the Toledo Sports Arena with Rare Earth. I wanted to go to that show. I didn’t go, but I remember thinking that was a great bill. No, I mean, that just wasn’t my taste. I don’t think it was ever a race issue. I’m sure it was a great crowd. Detroit really did have that. Detroit was a true Northern industrial city. When people worked in the factories, everybody worked together; you worked alongside all kinds of people. They had a different gig there.

MRR: Do you recall other bands (besides the proto-punk band Death) having mixed race members or black punks around Michigan? Did black fans ever come to your shows?

Sure, the Cult Heroes were a decent new waver junkie band from Ann Arbor whose singer was black, and there was the occasional black fan at the shows. Also, there were pick-up student waver and punk bands that had black players as well. I was in Strange Fruit, whose founder, Mike Love, was black. The Midwest had little race self-consciousness save for the skinhead losers, whom no one paid attention to. That came later with the other tourists, like Bored Youth.

MRR: Did the Fix really start off that blitzkrieg fast at the beginning, or was that something the band grew into?

MRR: Did the Fix really start off that blitzkrieg fast at the beginning, or was that something the band grew into?

We knew that we were going to play fast. It’s just we had to work up to it. We were starting with some pretty standard reference points, like the Dead Boys and stuff like that.

MRR: But you were twice as fast!

The idea was to start speeding this up. Then we met Tesco and Dave Stimson. They started turning us on to the sounds coming from L.A. They were saying that they’d heard of us, and would tell us, “Hey, you guys sound like theses bands.” They would bring out a record, and we’d listen and feel, “Yeah, that’s kind of true.” That’s how it works. We’d start playing the music, and subconsciously it would just start creeping into our sound. Craig, me, and Mike lived in the same house. So, you’d sit around, hang out, get drunk at night, and listen to that music. There’s no way around it. It becomes part of your overall lifestyle and culture.

MRR: Did you see yourself as isolated, or connected to a larger scene of this type of hardcore music, like Negative Approach?

Totally isolated because you were still playing to audiences that were uneducated. You might have a box of really cool singles at home, but it didn’t mean shit when you were playing some Red Carpet Lounge on Sunday night. You were playing for five people, and mostly those were just friends of the door guy. So, we were really isolated, especially early on. Then hardcore punk rock started kicking up a little bit. I mean, we had bands, but nothing like once the hardcore thing became recognized. John Brannon (singer of N.A.) was a little behind us, you know. I remember seeing him at shows early on. We had to get him into one of the shows because he wasn’t old enough.

MRR: How much older were you guys?

That’s another thing. It’s kind of funny. We were in our early twenties. These guys were in high school. So, I don’t know what took us so long, or why they started so early. I don’t know. I guess we had been solidly grounded in music. Like we just discussed, we enjoyed that 1970s music, but once punk rock happened, we started to go see every band. I remember seeing the Ramones and everybody who came through from the punk genre.

From what I know, hardcore music became ghettoized, forced to exist in places like the Cass Corridor, a kind of Detroit version of the Bowery

Yeah. You mean the Freezer? The Cass Corridor started developing later on. Probably at the end of the Fix run, around late 1981. Because we played there once, and it was a fine place. It was a standard ghetto place. I am trying to think what we played it for. Ah, the Process of Elimination gig. All the bands played there for that: Dec. 1981, just before we lit out on the 2nd U.S. tour. That seemed to be when a lot of the kids were taking over. They were moving shows out of bars and into small clubs. They were all about, “We’re not old enough to drink, and drinking is uncool,” but we were still rock’n’roll dudes at heart. It just so happens that we really loved to play fast.

There was no love lost between you and the Necros, right?

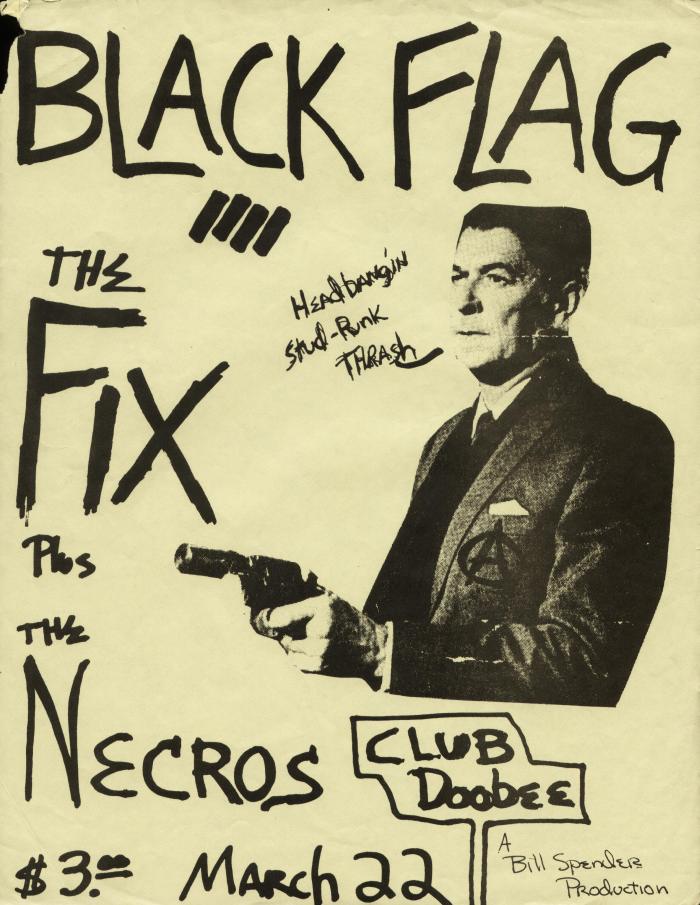

They were a clownish act. They were like punk incorporated, like if you sold punk to Wal-Mart, they just bought it. That’s fine. It just didn’t seem to have much grounding in anything.

I can’t think of another Midwest hardcore band that toured as early as you guys.

Well, we were just a little ambitious. We just thought, if nobody here will listen, why don’t we go somewhere where everybody is, so Jeff and I went down to see Black Flag. They were touring in Dec. 1980, and we went down there and thought we’d just go see them. Maybe we’d talk to them because they were going around on tour. Maybe they have some tips or something, we thought. So, we go down there on some wicked, cold ass night down to the Metro. I think there were two shows, and Dez was still the singer. Black Flag was still really good. We just walked back, and I met Chuck. He was the guy with all the numbers, and he gave me his number. I was like, “OK man, I will call you and we can put something together. I’d like to see if you can give me some numbers.” He said, “Yeah, that’s great.” He was real helpful. By that time, I think Toxic Reasons had done more stuff. They were from Indiana. We just knew their first single. We didn’t have any connection to them. But I knew they were playing shows, but at that time we didn’t have the Internet or anything, and it wasn’t like I could just find them.

What was the first show outside of Michigan you played?

Well, we played Ohio early on I believe. The first place where we really took it to an audience was in Chicago, at Oz, on Feb 13 and 14, 1981. That’s when we really said, these people like us, and they get it. That was the first time we felt validated.

Were the Effigies on that bill?

I think the Effigies were on that, or was it Naked Raygun? I can’t remember. I know it went so well we went back in April, and the Effigies were on that bill. We played again two nights, and I think they were on both nights too.

What were some of the most interesting moments of that tour?

That wasn’t a tour, just a drive down. The first time we went down there the place was fucking freezing. It didn’t even open until 2:00 a.m. So, we were like, “What time are we playing?” They were like, “4:00.” That’s gonna be a long night, we thought, freezing in there. But it was kind of cool. We were just sitting there. It was freezing outside. Most of the time you’d feel, well, at least we got the van. But it was too cold to even think about that. We were just bundled up, sitting there. Four little Fix guys just watching everybody come in. Not moving. It kept filling up. I don’t know how we did it because it was hard trying to get loose. You can’t get loose when you are just sitting there and freezing, and all of a sudden it’s like, “OK, you guys are up.” Somehow it worked fine.

I imagine many times you were on bills with non-hardcore bands.

Yeah, like we played with the Embarrassment in Oklahoma City, and shit like that. We were like, why? In Tucson, we played with some waver band. Maybe there weren’t any hardcore bands available, nothing like that.

But at the same time, it’s better than a few years later when all the cookie cutter hardcore bands sprouted up.

That’s right. That’s one of the reasons we got worn out by the whole thing. After awhile, especially in California, every band sounded the same — “Yeah, I am in a hardcore band.” We kept saying to each other, “They must have gone to the store and found out about punk rock.” They bought the franchise, so here they are. I don’t know. There’s something just wrong about that to me.

What was your relationship with Tesco Vee like?

Well, first I met Dave Stimson (co-editor of Touch and Go), and he was working at the Census Bureau at that time, where I was working, just as jerk clerks. We worked all day pushing paper and shit. Just a little money to fund your evening habits. So, he went and saw us, and Touch and Go was partly his magazine, of course. Then he says, “Tesco, you gotta go see these guys.” Tesco came, and he was just this goofy dude. He was very nice, helpful. Just flattering. We said, “Come on over to our practice place and have some beers.” That’s when he brought over those records, and we were like, wow. He said, “This is what you guys are aiming for, or going for.” He nailed it. We’ve known each other ever since, going on thirty years.

Were the engineers sympathetic to your sensibilities on the recordings?

We worked with an engineer who knew how to do what we told him to do. You know what I mean. It was one of those old places; well, do you remember in the late 1970s, during that era and time, there were these recording workshops, like “Learn How to be a Record Producer.” Because everybody’s gonna make a million dollars being a record producer! So, these guys would pay money and go learn how to work this gear. So, Jeff knew somebody like this down in Ohio. He was like, “We’ll do it for free. We’ll do a class project,” and we’re like, “Yeah, OK.” Tesco had already said, “If you do a tape, we’d like to put out a single.” So, we drove there. We knew what we wanted to do, so we just said, “Take the EQ off the guitar, and let it ride.” Obviously, we didn’t get the same results as when working with Spot (SST engineer). We still like it.

Tell me about the Spot sessions.

We knew Spot because of Black Flag came through Lansing and stayed at our house. So, we talked to him, and he was cool enough. Yeah, at that time we had to negotiate something. I don’t remember doing it. One of us had negotiated. He said, “Listen, we are going to be in L.A. in July (this was said in March) and are you going to be there?” He said, yeah, and my guy from the Fix asked if we could do a session. It was a cheap rate. I can’t remember what it was, but it was nothing. We ended up in L.A., doing it at Music Lab on Hyperion Ave. (in Hollywood). They were doing some pretty big sessions during the day, but he had this place at night. We said, “We’ll come in whenever.” I think we came in there at midnight. We scammed a place to stay with some girls in a nice area, so we’d stay there all day then go in and record two nights. We did it all live since we were so well rehearsed by then. There were no mistakes. I might have done a couple guitar tracks. Spot was so dead-on. He knew everything that needed to be done. We were blown away by it. You listen to it now and obviously there are all kinds of problems, but back then, we just wanted a big blast of noise. If we could have deconstructed it anymore, we probably would have!

How did you guys deal with each other on tour, in terms of the band relationship?

We got along really well, actually. I mean, you’d have your flare-ups, but in general, not at all. I might be one of the only singers that wanted the guitar louder! Because usually they bitch about it. When you were in the Fix, everyone else was the enemy. So, it was fun.

The band as a gang, not unlike the Ramones: us versus them.

Yeah, because where we came from, the Midwest, it always seemed a bit fractious. Some people against us, and stuff like that. You’d have the older punk rock crowd who’d be like, “No you guys suck,” then you’d have the kid crowd, “No you guys are blah blah blah.” So, it was like, “Fuck y’all!” If someone didn’t like us, that’s fine. We took it that way, but we were really well received everywhere we went. I can’t remember real horrible shows. Maybe Ft. Worth in 1981, in June on our first tour.

Was your whole work ethic in the band underscored by Midwest sensibilities?

It was. It was kind of like a machine. You just get in there and get it done.’ In a de facto way, that’s how the no break’ thing came in. Essentially we’d try and play our whole set through, no breaks. And that was because we would all have shit going on, so we’d all want to roam, get drunk, and do what you do. We were enjoying being in the Fix. At home, we’d get to the basement, a little hole. In the Midwest, we have basements, so that’s where everybody practiced. We’d crawl down there down this tiny, little narrow stairway. Get down there, flick on the lights, everybody would tune up, and we’d just go. We had the set list for the next show hung up, and that would be it. Bing bing bing. Everybody would want to get going, so we would just run through it, no breaks, that’s it. We did it four or five times a week. If we missed, it was like how people miss going to the gym these days. We’d be like, “Fuck, we missed.”

What about material that does not show up on the recordings? Were you playing covers?

Yeah. Early on, we did a lot of covers. We loved doing covers, but they worked their way out because of our sound. As the speed moved in, you’d have to have a pretty fucking fast cover to do it. We did that Box Tops song I think…

“The Letter”?

Yeah, we did that. Alex Chilton could write a burner, he just didn’t know it. I can’t remember any other ones. At one point, as kind of a tribute we did “Body Bag” by the Effigies. I’d love to have a live recording of that. We played with the Effigies before they released that first single. We thought, “That’s a great song.” We’d do it every third night, and mess with it at sound check. But we were like that even on the road. We’d want to rehearse. For instance, when we were in San Francisco, we’d stay for a week or two and we’d rent space from this guy Ian, who worked with Flipper. We became friends with Flipper, so we got this space. We could go down there and rehearse. I remember when we were recording that session down in L.A., we would go… Well, we got into town, found this place to stay, set up our stuff, practiced during the day, tore down, went down to the studio at night, and recorded. Go back to the place the next day, practice again, tear down, and go back down and record. We were really into it.

Looking back on the touring, what pops up in the mind more: the friends you met and the places you went, or the music?

Oh, the music. That’s a funny question. I wasn’t into the scene. It was about the music. Everyone else got into the franchise element of it, with punk. The beauty of it was that it was a lonesome thing. I always thought that was kind of fun.

So what led to the demise of the band?

There were a couple of things. We were all getting worn out on these bands. You’d go to a show and seriously, I can remember this very clearly, we went to Tucson, we pull into the parking lot of this club, back stage. We were sitting back there, and some dude, a punk dude with all his uniform on, his little punk outfit, and he starts talking to us. Craig says to him, “Hey man, (we all loved to smoke) do you know anywhere where I can get some smoke?” The guy’s answer was, “Uh, Black Flag played here last week.” We looked at each other and said, “What is wrong with this guy?” Craig said something like, “What the fuck is wrong with you? I asked you a question.” We were all really irritated, and I think it crystallized something right there, like “What is wrong with these guys?” It was like a bunch of brain dead soldiers. We were like, “Is this where it’s going?” This horrid and horrific sameness? And, so, we talked about it quite a bit in the van from that point on. Still, there were the greats: the News Years Eve show we played with Effigies, Dead Kennedy’s, and Flipper, our last blast show. We loved it. It was great. But it almost felt like we had done what we meant to do. We got back, and Jeff’s (drummer) Dad said he had to quit to focus on school. His schoolwork might have been dropping off; I don’t know what was going on. Jeff was really involved with extra-curricular college activities in addition to the Fix. I guess one of them had to give, so I guess it was going to be the Fix. His dad was a rich guy and had seen the Fix, and I don’t think he was amused at all!

Was there a class issue, because the Meatmen and Necros were not exactly poor kids? Were you working class?

No. Both of my parents were educators. It was a family of letters.

The music sounds so abrasive and rough and tumble, but it comes from sometimes affluent kids.

Iggy Pop was pretty well-to-do. His parents were teachers. Look at the guys from the MC5. So, this whole thing of it being born from some frustration out of being poor … It was not that way at all. That was probably more of a British thing, I would guess. British society was more class-based at that time. Ours was intense music that knows no class.

Do the records capture the spirit of the band?

I thought so. It caught us exactly where we were at — a snapshot of where we were at the time. You see the progression from the first to the second session, and on the re-issue you can really trace that whole thing. If we would have done an album, I think there would have been some more beat-flavored things. I think we were doing one song during the sound check near the end of the band that was definitely not so hardcore because… well, it’s funny because after the Fix broke up I went on to play guitar, which I always wanted to play since I was a singer by accident. Mike and I went on to form Blight. We were like, “Fuck it’s punk rock shit.” If everybody was going to go over there, we wanted to go over here.

Noise terror, huh?

Yeah. We wanted to do anything but what was expected. That’s where the Fix would have gone too. If the Fix would have kept going, I think it would have gone in that direction. Craig was really, really bored. He could have done all kinds of things. It seems to me.

So when John Brannon went on to form Laughing Hyenas, did that make sense to you?

Very logical. Because I didn’t care for any of that copycat stuff, those second generation, or even third generation hardcore bands. It didn’t do much for me, but John became a genius, an all-time rock figure. He’s one of the true rock’n’rollers.

Why didn’t Blight go any further?

It was just be us laying back and having some fun. Mike and I had a basement again. We just liked to play. We would have played even without Tesco. We were playing anyway. He just came over. We were having a beer and told him, “Come downstairs and check this out.” That was it: it was really simple.

Were you writing as a journalist at that time?

I didn’t become a journalist until 1994. I started writing for Your Flesh magazine in 1991, under Peter Davis, who still runs it, and he was a friend. I knew about music, and he just said, “Could you write about some stuff for me?” I said yeah, and that morphed into more traditional journalism. After that started, I just didn’t think about playing music. Words seemed more powerful to me.

Really?

Yeah. To me, I felt at home doing that. Plus, they actually provided me a paycheck. I was shocked by that!

If the songs offer a snapshot, may they be like journalism?

No journalism. I didn’t even know what that was. My dad was a journalist, so I’m sure there was like, “I’m sure not going to do that.” I wrote snippets. Craig wrote a lot of the songs.