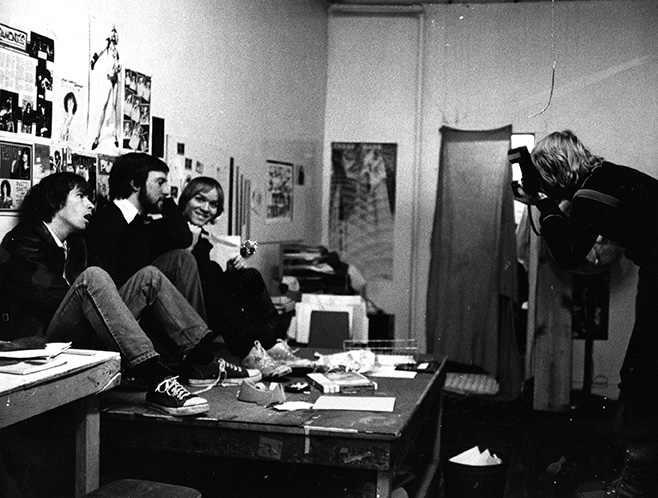

Punk magazine’s John Holmstrom

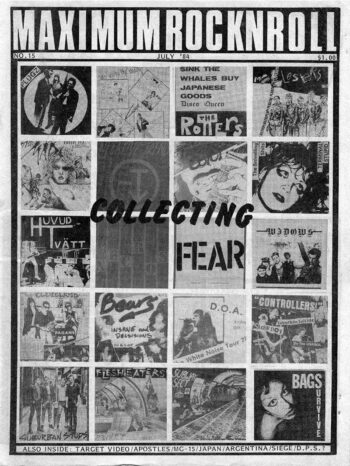

In case you missed it in MRR #311, here’s…

A Visit with the Editor of Punk or, How a Fanzine Changed the World

by Aaron Cometbus

News passed down the punk pipeline: a print media-themed issue of MRR! What better opportunity to sit down with the pioneer of punk himself, John Holmstrom? I’d admired his work since I was a wee lad, and had a long list of questions I’d always been dying to ask. He was amenable to the idea, and agreed to meet me at a nearby diner—the same diner, in fact, that held the fateful conference where Henry joined Black Flag. Hopefully this meeting would have a happier outcome.

News passed down the punk pipeline: a print media-themed issue of MRR! What better opportunity to sit down with the pioneer of punk himself, John Holmstrom? I’d admired his work since I was a wee lad, and had a long list of questions I’d always been dying to ask. He was amenable to the idea, and agreed to meet me at a nearby diner—the same diner, in fact, that held the fateful conference where Henry joined Black Flag. Hopefully this meeting would have a happier outcome.

However, a party of Ukrainians sat down for a post-wedding celebration at the next table over just as we began to chat. As a result, my tape recording serves as a better record of their conversation than ours. And so, with what direct quotes I can salvage, the story will proceed in my own words.

Holmstrom came to New York City from Connecticut in 1972 to learn to draw comics. He enrolled at the School for Visual Arts, but was disappointed to find not a single cartooning class. Along with some other angry students, he went to the president of the school. “Sure, what cartoonists do you want?” the President asked. “Put a list together.”

And so they did—a fantasy list of comic legends. Topping the list was Will Eisner (the comic maverick who’d created the Spirit in 1940, and, famously, turned down publishing the first issue of Superman) and Harvey Kurtzman (the founder of the original Mad magazine). The administration surprised the students by hiring both.

Studying under Eisner and Kurtzman was Holmstrom’s first entry into the worlds of comics and publishing. Their lessons, and their belief in him, greatly affected the course of his life. Even after he could no longer afford the steep SVA tuition and was forced to drop out, Holmstrom continued on as their apprentice, literally as well as figuratively: both Eisner and Kurtzman hired him as personal assistant. The work was part-time and paid only minimum wage, but that was all he needed to scrape by. More importantly, it gave the young artist an opportunity to hone his own skills…

Holmstrom’s first published work was Domeland, an educational comic book put out by Charas—later to become a Puerto Rican activist organization with a massive squat on Avenue B, but at the time a less political group operating out of an acre-wide lot on Cherry Street (leased for fifteen dollars a month) where they built geodesic domes. To Charas, these structures were the perfect shelter: indestructible, aerodynamic, affordable, and environmentally sound. Charas (and Domeland) promoted them as an answer to many of the world’s housing woes, and they were all set to go to India to demonstrate, with Holmstrom in tow. Then someone from the Indian government looked up the group’s name in a Spanish- English dictionary, and the deal was off. Instead, the domes were built in the South Bronx, where it took resourceful youth only two or three days to blow them up.

Holmstrom was embarrassed by Domeland, as anyone should be of their earliest work, and he neglected to keep even one original copy. His next output, a cover illustration for Screw (of a woman putting ketchup on a severed penis in a hotdog bun) embarrassed everyone else. But, he was getting experience, and other work on the side, doing ads. Kurtzman, who had landed Holmstrom the Screw cover, now angled him into a freelance job at Scholastic, drawing a monthly strip for Bananas, their magazine for seventh and eighth graders. “It was a great gig,” Holmstrom remembers. “Three hundred dollars per strip, and back then, you could get an apartment in New York for a hundred dollars a month.”

He didn’t always have the intention of starting his own magazine. Instead, it was a happy accident. Kurtzman had lined him up with yet another job, this one as editor of an ambitiously large, soon-to-be-launched humor magazine called National Harpoon, a National Lampoon spoof. Holmstrom was hired, only to find out that Harpoon’s backers had no intention of actually publishing; their plan was to get bought out by National Lampoon before even getting off the ground. But that disappointment turned into inspiration, setting off bells in Holmstrom’s head. “It started getting into my mind what I could do with a national magazine,” he says.

Helping Kurtzman had never been a steady job, and Will Eisner closed his office every summer, so Holmstrom was cut off from day-to-day work. He was restless. He ran into Eddie NcNiel, an old friend from high school with whom he’d once founded a comedy group. McNiel had stuck with the troupe while Holmstrom pursued other avenues, but was now sick of it, and restless, too. McNiel invited Holmstrom to join him in returning to their hometown for the summer to work for a painting business started by another old friend, Ged. Once reunited in Connecticut, the three men got along so well that Ged suggested they pool their energies and form a company — for publishing instead of painting. And so it was that in the summer of 75, in Ged’s downtown Cheshire apartment, Punk (and perhaps punk itself) was born.

As summer came to an end, Holmstrom returned to Eisner’s office. McNiel henceforth known by his nickname Legs—was making porno flicks at Total Impact, a hippie film cooperative at Second Avenue and 14th, sharing the office with such future film luminaries as Victor Colicchio (Summer of Sam) and Mary Harron (I shot Andy Warhol, American Psycho). Movie buffs may or may not want to seek out the one film all three worked on together: a porno called Blow Dry.

Ged went back to school to finish his degree, but called just a few months later: “Ah, I’m bored in school, I hate it here. Let’s start the company now.”

Great!

Holmstrom went out to find their new venture some office space, but nothing seemed right or within range. Having already given 30-day notice on his apartment, and with the date drawing close, Holmstrom was nervous. Then a real estate agent brought him to the no-man’s-land tucked in between Hell’s Kitchen, the rail yards, and the entrance to the Lincoln Tunnel. Abandoned train tracks ran overhead, rats the size of cats lurked on the docks down the block. The building for rent—a huge storefront, with a complete office set-up already in place— was eerily abandoned as if the previous tenants had disappeared into thin air. Sweaters still hung on the backs of chairs, half-full coffee cups rested on the desks. “We can get rid of all this junk,” the realtor said.

“No, no! It’s perfect!” said Holmstrom. “We’ll take it.”

Holmstrom and Legs came up with the two hundred bucks needed to secure the place, and Ged arrived a couple weeks later. The Dictators were chosen for the cover of their debut issue, but a quick call to Epic Records brought news that the band had just broken up. “Let’s go see the Ramones and do a story on them,” Holmstrom suggested. With a reel-to-reel recorder and someone from Total Impact along to take pictures, they headed to CBGB’s on the Sunday after Thanksgiving. After interviewing the Ramones, it turned out that Lou Reed was in the audience, and he reluctantly agreed to talk to them too, resulting in one of the most incisive and hilarious interviews ever published. The whole magazine came together fast; a bit of paste-up and it was delivered to the printer (the same guy who’d done Domeland) on Christmas. On New Year’s Eve Holmstrom stopped by to check on the progress, and, finding the printer hard at work, rolled up his sleeves to help.

On January 1st, 1976, Punk #1 hit the streets. CB’s was only two blocks from the printer, so Legs and Holmstrom were able to deliver their baby right into waiting hands.

Punk stood out immediately from other magazines of the period. Visually, it was striking, with bold graphics, bawdy cartoons, and photo-comic narratives inspired by the French “photo funnies” from the Forties that Kurtzman had brought into class. Instead of being textheavy, Holmstrom employed a “less is more” attitude, expressing his ideas with very few words. In part, he credits Minimalism: “Musicians weren’t hanging around art galleries, but everyone was aware of the artistic scene in New York at the time, and a lot of the better bands were trying to present a new visual form as well as a new musical form. I wanted Punk to be like that, too.”

Rather than focus on news and current events like the remaining Sixties underground papers, Punk covered the culture of rock and roll, and did so with a swaggering, take-no-prisoners attitude. It was intentionally shocking, the way rock and roll had once been, back when DJs smashed records on the air and Senate subcommittees linked comic books and rock and roll to juvenile delinquency. Holmstrom wanted to bring back that connection and run with it—not just the shocking energy, but the coupling of rock and roll with comics, two art forms that had grown up side by side. “There was this great music coming out of CBGB’s,” he says, “and I could tell rock and roll was headed in a certain way. I wanted to bring out a magazine that was sort of a combination of the Sixties underground papers and a comic book. We wanted to be the Mad magazine of rock and roll.”

So, the new rag that rang in the bicentennial was a synthesis of many unlikely sources: Forties French film mags, Fifties rock and roll, and Sixties underground press. Comic books (both underground and mainstream) and the original, Kurtzman-produced Mad magazine (rather than the later, heavily formatted version). The shittyness and grittiness of New York in the Seventies as well as art school ideas about Minimalism. But what really set Punk apart, what made it not just a groundbreaking magazine but the spark that started the fire which remains so close to so many of our hearts—that was something else. In large part, it was Legs’s fault. He had always wanted to be a P.R. guy. “Look,” he said, “if you want an idea to be successful, you’ve got to make it bigger than the magazine. We’re gonna start a punk movement.” He took a very small scene in a Hell’s Angels hangout on the Bowery and cast it larger than life. “I’m gonna be a punk,” Legs declared, assuming the role of pin-up boy and archetype for the new movement, one that’s changed very little in all the years since.

Of course, it was laughable, not to mention megalomaniacal. But, it worked. In New York, anyone could go down to CBGB’s, see that this “movement” consisted of three or four bands and a handful of their friends, then dismiss it outright. Not so in England, where, through distributors, Punk #1 reached readers who took Legs’s fantasy literally. Blondie returned from their first European tour with reports of London kids dressed up like Legs acting out scenes from the pages of Punk #1 and calling themselves punks. They took to it completely, only one thing missing: the music. Kids were dying of curiosity, asking, “What does this punk rock sound like?” In January 1976, there were no punk records yet in existence. The Ramones first UK tour, famous for supposedly launching the first wave of British punk, was still six months away. According to Rat Scabies of the Damned, the London kids formed their own bands by looking at the pictures from the pages of Punk and trying to guess what the music sounded like. Even when they got it wrong, they got it right.

The release of the Ramones debut LP also came about, in part, as a result of the first issue of Punk. “We got them their first record contract,” Holmstrom claims. “Our initial story on the Ramones convinced Seymour Stein from Sire Records that he had to sign them and make them the first hit out of CBGB’s.” The iconic image from the album’s front cover came from a Punk photo shoot, snapped by CB’s doorwoman Roberta Bayley in one of her first ever attempts to use a camera. As to the exact location of the photograph, it remains a mystery. Legs and Arturo Vega (Ramones’ art director) maintain that it was taken at the community garden on 2nd Street between First and Second. Holmstrom remembers it happening elsewhere, but as to where, he hasn’t a clue, and Bayley herself has forgotten too. (The photo on the third album was shot in the alley behind CBGB’s—that much we know for sure).

So, Punk #1 was an instant hit by all accounts. Subscription requests started coming in after just a few days. The Village Voice called Punk “the zeitgeist of a new generation”.

“That was our peak,” Holmstrom sighs. “From there, it goes downhill. Everything falls apart.”

The problem was a matter of perspective: what seemed like a success to Punk readers was a complete failure in the eyes of its creators, whose expectations were set much, much higher. They’d expected to get rich, or at the very least make a decent living from their efforts. Instead, months passed, and Holmstrom, Legs, and Ged were still sharing living as well as working quarters at the Tenth Avenue storefront— now known as the Punk Dump—and struggling to come out monthly and just pay the bills. Add to this the age-old problems of publishing: distributors that don’t pay, printers that are chronically late, advertisers who abandon ship if the magazine fails to come out on time. It was hard to reconcile the fact that Punk was getting tons of press and the magazine was an international sensation, yet it only seemed to get more difficult to produce instead of less.

Their visions of grandeur were perhaps unrealistic, but not unprecedented. After all, punk rock seemed poised to be the Next Big Thing, and they were right on the crest of the wave. Holmstrom explains: “I thought the Ramones would be bigger than the Beatles. I’d seen the examples of, say, Alice Cooper, who went from being the most hated, reviled rock band in L.A. to number one with a bullet. That seemed to be the formula for success in rock and roll. Everybody hated Jimi Hendrix when he first came out—he was kicked off the Monkees tour by the Daughters of the American Revolution— and then he became the biggest star in the universe. People hated the Beatles when they came out, they hated the Rolling Stones. Everything in rock and roll had this rebellious spirit that people tried to stop, and hated. So I figured, Hey, they hate it! We’re gonna be rich! We’re right where we want to be.’ Because, really, we were just following the formula for success. Only, ironically, when it came to punk, the formula stopped working.”

The bottom line was, they were broke. Despite daydreams of fame and fortune, the real goal was just to make enough to eat. Luckily, Holmstrom still had his freelance work for Bananas and other magazines on the side, and that provided enough for him to get by. In hindsight, he realizes that the magazine should have been subsidized by his freelance work and kept going no matter what. But, in the summer of 76, things seemed bleak. Their latest issue—Punk #5—was abysmal, shunned by readers and staff alike. With little remaining resources or hope, they decided to call it quits.

And that would have been the end of our tale, if not for the entrance one day of an unexpected visitor. Holmstrom was sitting around the Dump dejectedly when a man walked in and kicked his feet up on the desk. “I’m gonna make you rich and famous,” he said, punctuating his claim with a crisp hundred dollar for each of the Punk staff. With that, he bid farewell: “I’ll be in touch.”

The man was Tom Forcade, already a legend in the history of underground publishing, though our bewildered boys didn’t know that yet.

Forcade’s life deserves an article of its own, if not a full novel. Start in the Sixties with a small-time Arizona drug dealer who learned to fly, making his own trips over the border to Mexico and Colombia as a way to cut out the middleman; soon, he’d made a small fortune. Publishing an underground magazine, Orpheum, led to involvement with the Underground Press Syndicate, a half-dozen papers with an agreement to freely reprint each other’s work. Under Forcade’s stewardship, and thanks to his organizational skills, it grew into a powerhouse with 200 members worldwide. Next, he engineered a deal with microfilm company Bell & Howell to preserve for posterity all the Sixties papers, big and small, while providing them with funds to persevere for another few years. Called in front of a Senate subcommittee investigating pornography, he introduced the pie toss as a form of political protest. Angry at corporate control of rock music, he founded the Rock Liberation Front, going up against Warner Brothers for their attempted takeover of Woodstock, and confronting Phil Spector for pocketing the proceeds from the benefit album for Bangladesh. Forcade was everywhere at once, including the 1972 Republican convention, where police—finding smoke bombs in his van—accused him of a plot to assassinate Richard Nixon. He was forced to go on the lam—and that’s when his biggest epiphany yet hit: why not start a magazine to bring underground culture to the mainstream? A year later, his idea was a reality, and the magazine, High Times, was selling a million copies a month. Two years after that, he walked into Punk.

Forcade was a miracle, exactly what Holmstrom & co. desperately needed: a benefactor to bring their own dream back to life—one with unparalleled experience in distribution and publishing. It seemed a perfect fit.

P unk #6 followed, published under the auspices of High Times. It was their first full-length photo comic, a film on paper called The Legend of Nick Detroit, with Richard Hell playing the lead role and David Johansen, Debbie Harry, and the Talking Heads, among others, in support. The all-star cast was as much of an accident as the photo comics Kurtzman had done in the early Sixties featuring Gloria Steinem, Terry Gilliam and John Cleese (both later of Monty Python), R. Crumb, and even Woody Allen. For Kurtzman, like Holmstrom fifteen years later, those were just the people hanging around his office at the time.

unk #6 followed, published under the auspices of High Times. It was their first full-length photo comic, a film on paper called The Legend of Nick Detroit, with Richard Hell playing the lead role and David Johansen, Debbie Harry, and the Talking Heads, among others, in support. The all-star cast was as much of an accident as the photo comics Kurtzman had done in the early Sixties featuring Gloria Steinem, Terry Gilliam and John Cleese (both later of Monty Python), R. Crumb, and even Woody Allen. For Kurtzman, like Holmstrom fifteen years later, those were just the people hanging around his office at the time.

Nick Detroit was an innovative, exciting experiment. And, a complete flop. Forcade unceremoniously dropped Punk like a hot rock—though, later, he would be back. For now, it was back to square one.

Holmstrom’s history is full of such false starts and just plain bad luck, but also a surprising amount of eleventh-hour saves. Once again, a mysterious investor appeared, this one from Detroit, drawn in by all the Nick Detroit posters plastered around town. He dropped twenty grand into the coffers of the nearly-moribund mag, and soon the presses were rolling again, with some of Punk’s best issues to date. Issue #8 featured a cover story on the Sex Pistols, at a time when few in America had heard of the band. Unlike Legs, who considered the London scene a pale imitation, Holmstrom was thrilled by the new energy. “They improved on our formula,” he says. “When I first heard the Sex Pistols record, I was blown away. No, I was never competitive about it. That was Legs’s thing. Legs didn’t have an understanding that it would be good if punk rock happened in another city and in another way.”

Similarly, Holmstrom was supportive of the fanzines that followed in Punk’s footsteps (“just as long as they didn’t think they were better than us,” he says). The first issue of Sniffin’ Glue arrived in the mail in the summer of 76 with a fan letter from editor Mark P. “Then, all of a sudden,” says Holmstrom, “the third issue, there’s a shift. Then I’m getting letters like, Oh, you Americans, you’re rich, and you suck. We live on the dole. You don’t know what suffering is.’ What a load of shit! Here I am eating chicken livers and some kid over there is giving us shit.” Still, he acknowledges Sniffin’ Glue’s awesomeness (and, in truth, it was even better than Punk) but prefers its lesser-remembered London contemporary, Ripped & Torn. The flood of English zines was made possible by Rough Trade, who took the profits from importing copies of Punk and bought a mimeograph machine for all the kids to use to make their own. “They didn’t need us anymore,” laments Punk’s editor, sounding both proud and sad.

As for Legs, his involvement in Punk—though crucial at its inception—was actually rather limited, according to Holmstrom: “He contributed a little bit to the first issue, then took off with the second issue. Then he and Ged had a big falling out, had a fist fight on the floor trying to kill each other, and he was kicked out.” Legs returned, but borrowed Ged’s bed—and a bottle of maple syrup—for a threesome. That was the last straw.

Two cofounders were left, and, soon, they were embroiled in a conflict of their own. Punk #9 was all set to go to press—in Holmstrom’s opinion, the best one yet, featuring the Damned, a comic interview of Kiss, and advance excerpts of William S. Burroughs’ Junkie—when Ged announced that this issue would have to be their last; there was no money left. The twenty grand was already gone, pissed away on bad business decisions and the fancy, glossy paper that Ged had picked. The rest of the staff was justifiably pissed. “It was like the Julius Caesar assassination,” says Holmstrom. “We ended up firing him right before it was going to come back from the printer.”

Ged decided to get revenge. He went to the printer and told them that Punk didn’t have enough in the bank to pay the bill, which turned out to be the case. Holmstrom had to personally borrow money to get the magazine out of hock. Then the printer, now finally paid off in full, went belly up. Holmstrom never did get the magazines back, nor the cash; not even the originals, which included oneof- a-kind polaroids of Burroughs and Ginsberg in Mexico hanging out on the beach.

Not only was it a disaster in every respect—friendship included—but Punk was now in debt. Someone suggested a benefit, and a whole weekend of shows at CB’s was quickly set up. Blondie, Dead Boys, the Cramps, and Patti Smith all played. The Dictators’ Ross the Boss jumped onstage to jam, as did Fred Smith, who had left Blondie to join Television, confident that they would be the more successful band. That was when the paradigm at CB’s was undergoing a radical shift: Blondie and the Ramones— both of whom had been considered a joke—were becoming hugely popular, while the more polished, groomed-forsuccess groups were left in the dust. Blondie’s contract on the small Private Stock label was bought out by Chrysalis. The Ramones’ label, Sire—then still a small independent—was bought up by Warner Brothers.

Punk Rock was now a big business. Punk magazine was still a total bust. As always, the musical aspects of the scene received support and acclaim while the print media that formed its cultural underpinnings (and helped promote the bands) ate shit. That set the tone for what was to come, three decades of great fanzines morphing into mostly mediocre record labels (Slash, Touch & Go, Sub Pop, Lookout, No Idea) and fanzine editors who achieved renown only through their later bands (Kevin Seconds, Thurston Moore, King Vitamin of the Butthole Surfers, Dave Grubbs of Slint). Anyone who’s done both a fanzine and a band knows that playing music is always more rewarding, and—kill me for saying so, but it’s true—less work.

At any rate, Holmstrom was back in the black after the benefit, and back at the grind. However, the issues that followed were lacking a little spunk; someone had taken the piss out of Punk. The magazine mirrored what the Ramones were going through at the time—a process of simplifying and boiling down to basics, paired with increased production values and a nod to the mainstream. Rocket to Russia and Road to Ruin were certainly great albums (and drawing the art for both earned Holmstrom enough to get his own apartment and move out of the Dump). So were the corresponding issues of Punk. But, getting to the heart of the matter meant becoming a bit tame and formulaic in the process (and the coming addition of full-color photos helped neither the band or mag). To further the analogy, it wasn’t until the much later Too Tough to Die that the Ramones finally reconnected with the spirit that had made them so special, and they did so not by paring down but by branching out, surprising everyone by incorporating hardcore into their trademark sound—in essence, taking the fruit from the tree they had planted in the first place. Punk’s version of Too Tough to Die was Mutant Monster Beach Party, a full-length photo comic starring Joey Ramone, and it also came about after a period of stumbling around in the wilderness. Yet Mutant Monster Beach Party was a true masterpiece: an amazing mix of music, photos, comic illustration, and a deranged plot about juvenile delinquents—a climax of all the disparate elements of Punk coming together in perfect harmony. The issue was, of course, another total loss, but if you measure success by sales alone, sticking to a predictable formula is best.

In the meantime, Forcade had reentered the picture. Not only did he agree to go back to publishing Punk, he enlisted Holmstrom for a pet project of his own: an underground movie documenting the upcoming Sex Pistols U.S. tour. Forcade had grandiose ideas about the movie—sure to gross a million bucks—and the accompanying book that Holmstrom would produce (plus a special edition of Punk). Most of all, he wanted to get back at his old nemesis Warner Brothers, the corporate profiteer, who was running the tour. And so, they set off with a crew to follow and film the band as they wound their way through the entrails of America, leaving a path of destruction in their wake. But things with the film did not go as Forcade had foreseen. Warner Brothers remembered him all too well; they wanted nothing to do with the pie-throwing, Phil Spectorconfronting madman, and they did everything in their power to prevent his movie from being made. Meanwhile, back at home, Forcade’s staff was in revolt, afraid that High Times would go bankrupt from all the hundreds of thousands of dollars being draining from its account on some ridiculous-sounding escapade. And the Pistols themselves were of course a total mess, finally self-destructing in San Francisco like everyone else. As Holmstrom arrived back in New York, so did Johnny and Sid, the latter dopesick and headed for the hospital, the former crashing out on someone’s floor, without money enough to make it the rest of the way home.

What a hell of a week and a half!

Forcade’s movie, DOA, turned out to be yet another casualty of that tour—it took a full three-and-a-half years to come out. On only one count was he right: Punk’s Sex Pistols tour journal was their best selling issue yet.

Forcade had promised to make Punk as successful as High Times, and It might have even happened, were it not for the exclusive distribution deal Forcade signed with the notorious Hustler publisher, Larry Flynt. The ink was still fresh on the contract when Flynt got shot. “When that fucker shot Flynt, he pulled the rug out from under us,” Holmstrom says, shaking his head. “High Times started getting late payments for their distribution. The whole company was thrown into chaos.”

“Oh, I’ve got a million of them. A million reasons why we weren’t successful, and that’s just one.” Less laughable—and a more accurate shot—was Forcade’s suicide later that year, which severed Punk’s lifeline once and for all.

To enumerate every failure of Punk would take all night, and any reader of this rag has enough of her or his own bad luck to contemplate. Besides, my coffee was getting cold, the waitress having cut us off after realizing we weren’t going to order anything more than a side of perogis and a grilled cheese. Mercifully, she let us stay; the place was otherwise empty now that the wedding party had left, and outside it was pissing rain.

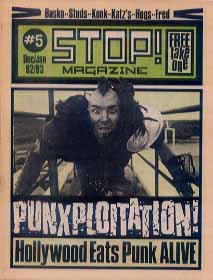

Holmstrom’s story was always ending but never over. Like the scene of the same name, Punk died again and again. It wasn’t until 1981 that it was really down for the count. Altogether, eighteen issues had been produced, three of which never even came out (lost to the inky clutches of every magazine’s best friend and worst enemy: its printer). But, rather than rest—or learn his lesson—Holmstrom leapt right back into the fray with a new publication called Comical Funnies, a collaboration with three other cartoonists that had been involved at the tail-end of Punk: Bruce Carleton, Ken Weiner, and the then-unknown, fresh-faced Peter Bagge. Holmstrom felt invigorated to work on a project completely divorced from the music industry, and he remembers the parties—and collaborative energy—of Comical Funnies fondly. Inevitably, it couldn’t last: Bagge and the others were headed towards full-length comics while the somewhat old-fashioned newspaper editor in Holmstrom yearned for a more mixed format. His next magazine, a free monthly called Stop, reflected that. One highlight was Holmstrom’s article on “Punxploitation” in Hollywood movies; at a time when nearly all old punks were writing dismissive, self-serving drivel about the new generation and the meaning of punk, he was insightful, articulate, and generous.

Holmstrom’s story was always ending but never over. Like the scene of the same name, Punk died again and again. It wasn’t until 1981 that it was really down for the count. Altogether, eighteen issues had been produced, three of which never even came out (lost to the inky clutches of every magazine’s best friend and worst enemy: its printer). But, rather than rest—or learn his lesson—Holmstrom leapt right back into the fray with a new publication called Comical Funnies, a collaboration with three other cartoonists that had been involved at the tail-end of Punk: Bruce Carleton, Ken Weiner, and the then-unknown, fresh-faced Peter Bagge. Holmstrom felt invigorated to work on a project completely divorced from the music industry, and he remembers the parties—and collaborative energy—of Comical Funnies fondly. Inevitably, it couldn’t last: Bagge and the others were headed towards full-length comics while the somewhat old-fashioned newspaper editor in Holmstrom yearned for a more mixed format. His next magazine, a free monthly called Stop, reflected that. One highlight was Holmstrom’s article on “Punxploitation” in Hollywood movies; at a time when nearly all old punks were writing dismissive, self-serving drivel about the new generation and the meaning of punk, he was insightful, articulate, and generous.

By 1983, Stop was over and the freelance jobs had dried up (Holmstrom’s art for the Ramones had somewhat backfired, making his style synonymous with the band rather than leading to other work). For regular employment, he returned first to Scholastic and then to High Times, where the new editor knew his comics and remembered his old association with Forcade. His first assignment: an illustrated interview with Eldridge Cleaver, which Cleaver later wrote to thank him for (despite a few cheap shots, it was honest, which he appreciated).

Holmstrom stayed at High Times throughout the late ’80s and all of the ’90s, slowly rising up the ranks until he was publisher. In that role, was able to bring the magazine back to its most successful peak. But the work eventually got to be too stressful. In 2000, he left the magazine (except for the Pot 40 list on the back page which he still writes, a spin-off from the old Punk top 99 and 40 lists). “I’d saved up a lot of money,” he says. “and I decided to try to bring back Punk.”

The results were mixed; the response, worse. Some accused him of a cynical attempt to cash in on the newfound popularity of punk rock; others, of trying to relive his lost youth. Both charges contained a bit of truth. Like most reunions, the relaunching of Punk was unwise and a little embarrassing, but not particularly cynical or ill motivated. Anyway, Holmstrom and the newly arisen Punk were soon subject to the same old school bad luck they’d always enjoyed. Terrorists blew up their office downtown. Distributors ripped them off. And a publisher could not be found.

“I tried to do it out of my apartment,” he says, “but it just about killed me. I live on a fourth floor walk-up, so when you have to walk up and down the stairs carrying boxes of magazines, it’s just too much, especially at my age. And the lines at the post office, and the four-block walk to get there. Anybody can put out a little fanzine out of their apartment, but if you’re gonna do 10,000 copies, you need to spend money on an office.” (I politely disagree, but happen to be blessed with a second floor walk-up only two blocks from the post office—though not with the absurdly cheap rent of an apartment moved into in 1977 with a check from the Ramones as down payment. Sigh.)

And what’s Holmstrom up to now? Not what you might’ve guessed. He’s pleased as Punch about a licensing deal just signed with a clothing company in Japan.

“They’ve brought out this crazy line of clothing,” he says, gushing a bit. “It’s very high quality stuff, like ‘Punk’ in glitter lettering on a very expensive women’s top. Little girl pants with the antidisco editorial from Punk #1 and ‘John Holmstrom’ printed on the inside. They’ve got coats and hoodies with the Punk logo on it. I’m a big brand in Japan right now! They even like some of my characters from Domeland. They want to make toys and action figures out of all this stuff. It’s kicked my creativity in a whole new direction. I’m preparing to bring out this stuff in America, and I think it’s going to sell really well.”

We shall see.

With a gleam in his eye, he explains: “It’s like a reward for all the crap I’ve put up with over the years.”

Check out John Holmstrom’s blog at www.johnholmstrom.com

And Punk magazine’s website at www.punkmagazine.com