RIP, Fred ”Freak” Smith, Black Punk Pioneer

A few weeks ago, a “semi-transient African American man” was found dead, killed from a knife wound behind the softball field of Las Palmas Park, located in San Fernando, CA. This was Fred “Freak” Smith, beloved guitarist who shaped the trajectory of mid-1980s punk in seminal bands like Beefeater, one of Washington, D.C.’s most inventive outfits. Having recently tried out for the band Romones, he had been living at Blake House, a group home, for a short stint, but wound up traversing the restless streets, seeking solace where he could.

The legacy of Beefeater is summed up most forcefully in their brilliant, genre-blurring LP House Burning Down, released on Dischord after the band’s demise in 1986. Combining hard funk, tribal stomp, raw jazz, shades of reggae, metallic leanings, and hardcore prowess, it’s an unmatched landmark, even now. Yet, the band was unstable (drummers came and went) and their fiery brand of politics set the teeth of both right-wing and left-wing punks on edge.

Smith, who changed his name to Freak, was the nimble musical backbone of the band. After joining Strange Boutique, he also helped pave the path of elegant post-hardcore music in D.C. as well. In the last half decade, he shredded in American Corpse Flower. And wherever he went, he was described as vivacious, spirited, generous, and skilled to the core.

As Bobby Sullivan, singer of Soulside and Rain Like the Sound of Trains, texted me earlier today: “Fred Smith was/is a larger-than-life character who literally lit up my youth. As a young person immersed in the D.C. punk scene, I had an extra in: my older brother lived at Dischord House. That meant I saw many of these bands form, from first talking about it in the living room, to practicing in the basement, and then taking it to the stage. Onam (Tomas Squip), the singer of Beefeater (Fred’s band at the time) also lived at Dischord House, and I spent many mornings with him when I would sleep over. My brother was a late sleeper, so I’d end up in the kitchen getting breakfast together and chatting about all the things I wanted to bounce off my older brothers and sisters — all the fine folks on the Dischord roster in the eighties.

Fred was somewhat of an aberration in that crew. Unabashedly cussing, drinking, being himself with no fear of judgment, he was something to behold. He was also a very skilled musician bringing a different flavor to that scene, which was sorely needed. My most poignant memory of him was when my band Soulside played with Beefeater at D.C. Space, I’m guessing in 1985. Scott, our guitar player, asked if he could borrow Fred Marshall half-stack and Fred replied, Yeah mother fucker! And do what ever you have to do. Smash it if you need to!!!’ We all knew he was serious because that’s exactly the type of guy he was.”

Other D.C. rockers like Jason Farrell of Swiz/Bluetip/Red Hare recall his outsized personality too. He emailed me this recollection:

“In 1984, I was a 14-year-old little skater kid just starting to go to shows, meeting other skaters/hardcore kids, taking every opportunity to stage dive, reveling in this crazy scene we stumbled into. I didn’t yet know much about the smaller D.C. bands that were percolating at the time (Rites of Spring, Beefeater) because all my friends and I were focused on whatever Government Issue and Marginal Man were doing.

“I’d seen Void a few times prior, but they didn’t really click with me until this one Wilson Center show… they were killing it. But apparently, it wasn’t enough to satisfy this big black dude who kept screaming and heckling them from the pit… I better hear some motherfuckin’ My Rules!!!’ Goddammit!!! If I don’t hear My Rules’ in the next ten seconds I’m gonna kill every motherfucker…’ etc. It was kind of funny at first, but then it got kind of weird and a little scary.

“After a few songs like this, the air was tense …The singer seemed nervous. People didn’t know how to react… my little friends and I thought some shit was about to go down, and whatever it was would be beyond our capacity. But then they played My Rules,’ the place exploded, and this crazy dude was overjoyed.

“In the time since, I have convinced myself that this crazy man was Fred Freak’ Smith.”

Our counterculture needs to reckon with the future. More and more legacy punks deserve attention and advocacy. I have personally seen medical issues sideswipe those I have been lucky enough to play alongside—like members of Mydolls, Anarchitex, Big Boys, the Dicks, the Nerves, and the Hates. Others, including Dave Dictor of MDC, have partnered with me on projects. But all have dealt with dire health issues. As punks age, they often feel economic duress quite intensely. While some cities like Austin and Denton (both in Texas) have set up some infrastructure and programs for musicians, much more needs to be done.

In addition, punks who are female, queer, people of color, and/or disabled (some prefer the term differently abled) are even more at risk, due to ongoing discrimination. Thus, those fighting for justice, equality, and fairness should not merely protest Trump’s agenda, they need to react proactively to the issues affecting a growing segment of punk veterans struggling to pay bills, maintain homes and health, and stay free and productive.

Buying old records is not enough. Antifa is not enough. But each of us can change that.

—David Ensminger

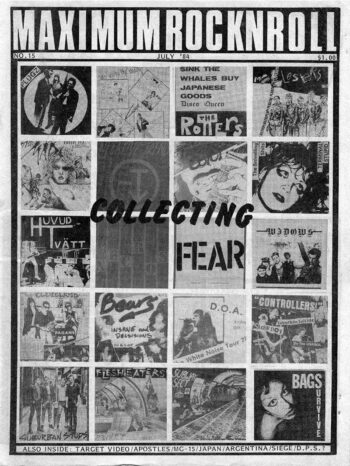

This interview was originally published in Maximumrocknroll magazine #324, May (out of print).

David: Tell me about your musical heritage.

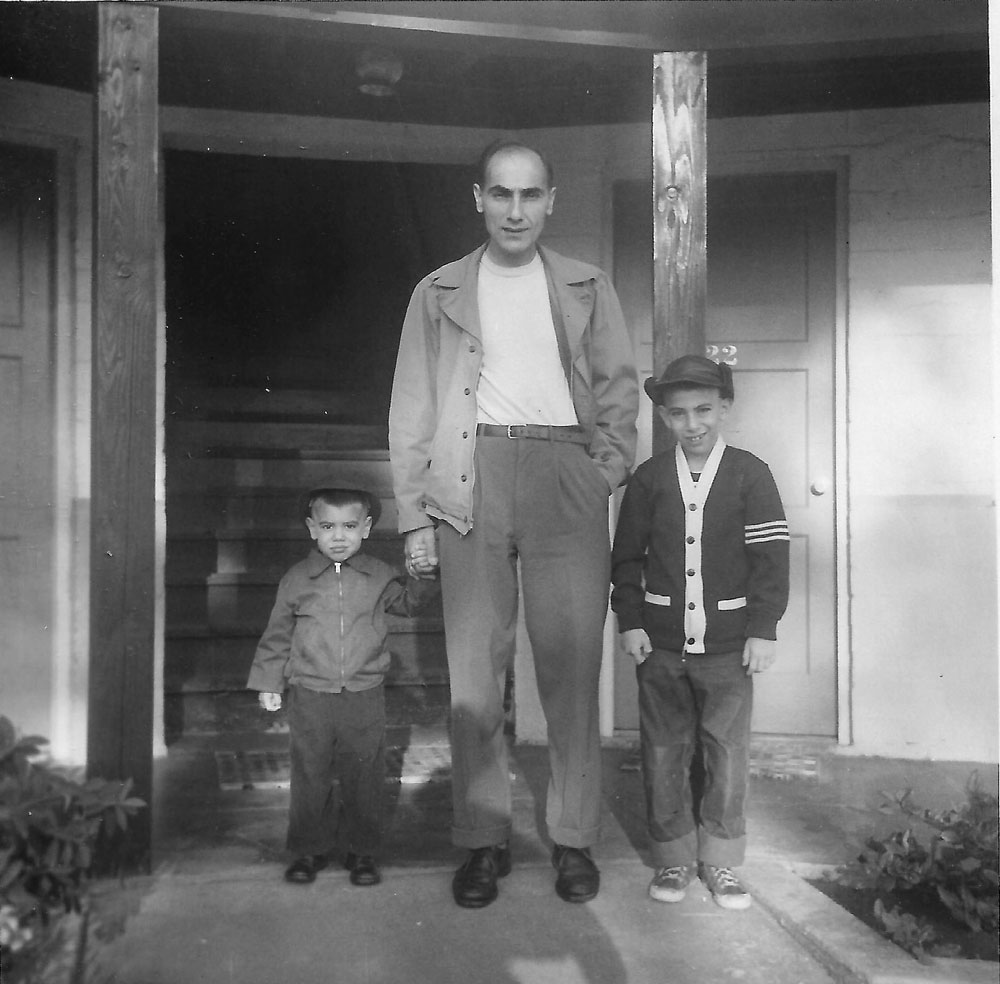

Freak: In very early 1983, I had just quit my government job at the Department of HUD. My dad was one of the first black Deputy U.S. Marshals. My dad was a doo-wop singer in the 1950s with Marvin Gaye and Van McCoy. The band was called the Starlighters and had a hit song called “The Birdland.” After they fizzled out, my dad got into law enforcement—the second generation of the Smith clan to do so. My mom was overseas working for the State Department (a gig she earned struggling in the ranks for at least fifteen or so years) while working for a 1960s program called “Voice Of America.” They divorced in 1971. As my dad kept stressing me to go into law enforcement as a lifelong career, the music side of me was tearing me apart. So, I finally decided for the latter.

And you started to immerse yourself in punk music?

All this punk rock shit was happening in D.C. as well as New York, Massachusetts, Michigan, Ohio, and L.A. I was so intrigued. It was kind of like the Hippie movement of the early 1960s but more radical and more in your face—”We are sick of this shit world, and we are now here to fucking change it whether you fucking like it or not” attitude. In this circle of mostly pale, tattered clothing, safety-pinned boys, aside from the few black fans in the audience, there was us! Gary Miller, aka Dr. Know of the Bad Brains, John Bubba Dupree from Void, Stuart Casson of Red C and the Meatmen, and the late great David Byers of the Psychotics, Chucky Sluggo, HR, and myself. Now I am just noting the guitar players, but would never, ever, exclude or forget Shawn Brown from Dag Nasty, their first original singer, and the late Nikki Young of Red C.

Through friends & some various acquaintances, more notably a guy named Ray Tony aka “Toast” and Eric Laqdemayo, aka Eric L from Red C, I heard about Madam’s Organ and the Atlantis Club. Soon I was auditioning at old Dischord house for a band that, from the start, proclaimed, “We are not here to make any money, are you in?” My brother Big Myke said, “Fuck this” and split. I hung around. Beefeater had an amazing, but at any given time, a very tumultuous run, with two vegan, militant vegetarians and throughout the two and a half years of our existence, three meat eating, substance abusing alcohol driven drummers, and myself!

What was it like to be a black punk in D.C.?

Let us all keep in mind that D.C. is what, 80 percent black, and this punk rock scene was fueled by angst-ridden white kids, a lot of whom I found out had fucking trust funds waiting for them when they became of legal adult age. Shit, I didn’t even know what a fucking trust fund was back then. It was very strange to be these “token” Negros playing in front of predominantly all white audiences, but we did it. As Shawn Brown and myself will attest, there were fucking issues man. A lot of fucking issues that we had to address when we did shows. When I first heard someone refer to me as the “negro Lemmy,” I was floored. I immediately lowered my mic stand down from the height that I set it. When I heard Shawn Brown being referred to as “the negro version of Ian MacKaye.” I was floored again. When I told him, he was taken aback but still plugged on. In retrospect, even in this new scene, I was always wondering, would racism ever end?!

Most of us know you as Fred Smith, so tell me about the name change to Freak.

Like many blacks back then, through the 1930s until the early 1960s, a lot of fucking name changing went about due to many horrible scenarios always occurring in the segregated United States of America. I legally changed my name to “Freak” some odd years ago. My birth name, Frederick E. Smith Jr., is not my real name. My real last name is Ellis. When I found this out in 1980, I was horrified, shocked, saddened, and felt raped by both the world itself for letting me be born as a lie and my parents, who knew this shit but never told me until I was an adult. So not cool, man. There was some incident with one of my family members in the 1930s in another state, possibly a homicide. I really don’t know. If this was the case at the time, I am very sure it was probably in self-defense against not getting lynched. My family keeps it very cryptic, but the truth was, this individual had to get out of town, disappear, and begin a new life. So, in doing so, the name was changed to “Smith.” I have never tried to find our true lineage and probably never will. That would be too much of a strain for me right now and would probably just make me very, very fucking angry to find out all the lives I could’ve known all these years but didn’t because of this incident. And a lot of other blacks will tell you I am not alone with this issue. So, changing my name finally gave me peace that I had been seeking for a very long time.

Being a drummer, I have to ask: why did Beefeater have three drummers, one for each recording?!

Beefeater had three drummers due to the fact that three drummers went through Beefeater. What I mean to say is basically guys came in and left for various reasons—theirs and ours. Bruce Atchley Taylor, our first, left due to the fact that his life was changing and he wanted not to tour. We were very ready to go out of town during the early stages. Mark Schellhaus, our youngest skinsman, was pretty much asked to leave by Doug and Tomas due to various addictions and attitudes at the time. I never got over that one. It was a band vote, and I was pretty much out-voted and pressured. If he wasn’t out of it, the band would’ve ended, or at least gone on without the two of us. Again, that is a very painful part of the history of the band for me, and I am still not quite over it. Mark and I are still very close, and he took being asked to leave pretty cordially and just did so without much opposition. To this day, Mark is one of the coolest people I know—a very talented fucker like the rest of the other drummers. Again, it was a sad moment for me. Kenny Craun, Mark’s replacement, and drummer number three, just came in and took us out thru the rest of our days and just went his own way to do other project when the band dissolved in 1986. Most notably with a punk outfit called the Rhythm Pigs, and he also hooked up with Chuck, Faith No More’s first original singer. With bands, chemistry is vital, and for some reason, the boys, Tomas and Doug, were okay with Kenny. This was pretty unusual at the time for Ken was more of a rocker than a punk dude, but he had his style, and they really didn’t buck at it much. The timing was funny, each drummer played on his own individual album, thus leaving his distinctive mark—funny.

“Need a Job” came out on Olive Tree Records, which a member of Lunchmeat described as “a shady short lived label, part of the HR (Bad Brains) Dave Byers crew . . . I doubt those tapes even exist.” Everyone knows Dischord Records, but tell me about Olive Tree.

Hmm, for me, “Need a Job” is one of my favorites. The band was really getting out of the standard basic hardcore genre and were really starting to mix that genre with funk. On “Plays for Lovers,” the funk was there, but it was being played so fast that those grooves might have gotten lost in translation to some. It was being accepted by a new breed of hardcore punks actually hearing that fast groove, somewhat like the Big Boys were doing in Texas. Though the production for the “Need a Job” recording wasn’t exactly what I was hoping for in a finished product, I was still glad the EP came out to show that we were growing as a band. As I remember, the actual Olive Tree label was established by some of the punk/rasta scene in D.C. Founding members of that label were Julie Byrd, Kenny Dread, and HR himself. Shady is a harsh word to describe the label, but… things sometimes did not happen in a timely and professional manner. Shit got done, but not without drama of some kind. Oh yeah, there are master tapes out there with shit still waiting, I hope, for life to the world. Everyone at Olive Tree just smoked too much pot sometimes. Not saying that liquor and drugs don’t affect other aspects of labels and bands and the music scene, I am just stating a known fact, and as musicians we have all pretty much really been there.

When interviewed in MRR, the band listed people like the Isley Brothers, John Coltrane, and John Lee Hooker as influences. Is that why the band had such a melting pot sound—pulling from jazz, funk, and world music—because the band wasn’t simply listening to Minor Threat records or mimicking 1977?

Fuck yeah, man. Beefeater, throughout its existence, listened to pretty much anything. We all were into our own worlds and brought them to the lab all the time. We took from this and that and just blended it into something. We fucking pulled from anything and everything. It was cool. Nothing was off limits. That is what made it cool. That is what kept things fresh. Yes, we were a hardcore band, in essence, but we had a lot more shit to experiment with, and we made damn sure we did. No restrictions.

I know Tomas was critical of go-go music (the genre of bands like Trouble Funk, who played with Minor Threat) because they often emphasized materialism (once called it “stupid music about dancing and being cool”). Do you feel he misjudged or misunderstood go-go music?

Tomas’ judgment of the D.C. go-go scene was, in fact, his opinion. Whether it was a critical misjudgment of it, dunno. You would have to ask him. I couldn’t stand the shit myself. Non-blacks have always loved grooves. It took forever for those to admit it, but they fucking love funk, soul, and grooves. I think at one time in the U.S., it was against the norm to reveal liking such music, but alas, times always change. Go-go to me was just a rip-off of bands that played stadium shows and gave the drummers a spotlight in the middle of the set. Go-go basically took that spotlight drum part and made it a one and a half hour-long song. Just basic jam sessions really, only highlighting a beat, the beat. Everything else—guitars, keyboards, etc. were put on the back shelf. The actual song was the beat. I didn’t care for it, but tons of fuckers in D.C. and around the world loved it. How can a hundred Frenchmen be wrong?!

Looking back, the band is considered part of the Revolution Summer era, including Rites of Spring, Embrace, Marginal Man, Gray Matter, and others. Did you feel a kind of “movement” was happening, or is our notion of that time really a kind of myth making?

Probably about a good four years prior to me even joining Beefeater, I, in fact, was becoming, in essence, a fucking real punk rocker. Learning the values and creed of that phenomenon and adapting it to my lifestyle. Revolution Summer was fucking bad-ass and very, very real. I am so proud to say that I was a part of that shit, and it was no myth in any way, shape, or form. I remember us out there doing the Punk Percussion protests at the South African embassy and Reno Park shows and shows benefiting those privately funded organizations that actually help and make change for the good of the city’s poor and under-privileged. That was a beautiful and awesome awakening for me in the punk rock world. All of us weren’t fuck-up miscreants. We actually cared about real positive change, and we went out there to do it at any cost. Fucking cool man. Great memories there. And the bands and individuals who were out there with us at that time all have my sincere and undying respect. Again, when I say it was fucking cool man, it WAS fucking cool. I believe my friend Amy Pickering of Fire Party started the whole concept. Again, way cool.

For many on both the Left and Right, Beefeater was vexing. Obviously, the Right dismissed the vegetarian/environmental/ “political correctness” of the band, but even the Left was baffled by the anti-abortion stance of some members as well. What was your personal sense of politics at the time?

From day one, Beefeater was Doug and Tomas’ vision, and it came with at least a couple of ground rules that the band stood for: vegetarianism/non-alcohol, environmentalism, and total political awareness and civil and human rights. No matter who was in the band at any given time, this message was creed. Now, with that in crystal clarity, Beefeater was comprised of four members struggling in groups of two. On one side, there was militant animals rights/vegan/non-alcoholic activist fucks, and on the other alcohol drinking, women fucking, and at the time chemical experimenting, meat eating pariahs. As you can only imagine, this chemistry caused, on more than several occasions, problems. With most bands, this is usually considered a marriage, albeit ours was a very fucked up, dysfunctional one, insanely. But we all definitely had no issues or disagreements regarding a woman’s right to choose and gay and lesbian rights. At shows, we were always very vocal about what Beefeater stood for, even though at times you saw beers on a Marshall or near the drums. I know that was hard for Doug and Tomas, but they put up with it. But not for very long. All the drummers and me tried our best to respect them and their messages as much as we could. It was hard considering our lifestyles and various vices at the time.

Supposedly, at your last show, which happened at Fender’s (I once read), Gang Green played after Beefeater and were vocal about being anti-PC and anti-Beefeater. Do you feel that other punk bands were pretty hostile to the politics of Beefeater, or feel that the politics overshadowed the music?

Beefeater’s last show was not at the Fender’s Ballroom in Long Beach, California, in 1986. I really don’t know where that came from. As far as Gang Green is concerned, dissing us at that show after we opened for them and others, that was just a retaliation for an incident that happened early on that same tour in a different city in which the show was overbooked. They showed up and weren’t allowed to play, and the promoter asked us to step in and talk to them about it. Not a good day for them at that time, but on the road shit happens. They said what they said, and so what? Gang Green is one of the great bands of the early and existing punk rock scene. I got no beef with those fun, crazy motherfuckers whatsoever. Shit, I used to work at the 9:30 Club in DC, as we all know, and those guys and me are all right. No issues at all. What was done was done. As far as bands hating our brand of politics on issues or whatever…shit! It just depended on what bill we were on, whomever that night was doing something totally stupid, like starting fights for no reason during our pits, racist skins sieg heiling us, dudes trying to get girls out of the pits, out of control bouncers, etc. Any form of bullshit we did not tolerate whatsoever, and we would stop performing at any given second until those issues were addressed by the crowd or the club. Whether the bands or fans gave us shit, we were able to handle anything. Not always contain it. But it got fucking dealt with as best we could. I believe our last show was in Washington D.C. in 1986. A sad show, but one that needed to happen so members could progress and move forward and still grow individually. Thankfully, everyone did.

I know Tomas has been critical of the punk scene, once telling a zine: “In a way they [punks] are society now too and that’s a shame. They still buy 7-11 food; they have no impact on the government, or the economy. They still entertain themselves the same way, they have the same values and futures as everybody else . . . so there’s no anarchy, rebellion there at all.” Did you feel that punk represented an alternative society, or not?

If here ever was a true punk, Tomas Squip was one of those at the head of the pack, for real. Tomas really didn’t give a shit about living beyond menial means—food, shelter, lifestyle. He lived at the Dischord House for a while in a room, shared a bathroom. He slept on the floor with no furniture. His pillow was a medium sized rock and he had a blanket to cover himself. He was always reading and constantly on top of all the news, local and global, and on every political issue on the grid. That fucker probably doesn’t even know it, but he taught me so much about the world, the system, and us as human beings. He really wondered why punks were doing the same things as everyone else did—get fucked up, do stupid things, resulting in altercations with law enforcement, and not really trying to distinguish themselves from the norm they were rebelling against, other than clothing and music association. He wondered why people, including myself at the time, didn’t try to alter their eating habits to respect animal rights, to change daily aspects of their lives to respect the earth, to be aware of things that are said at times that are racist and sexist and homophobic. He always thought a lot of punks weren’t really trying to make change at all. No rebellion or real anarchy at all. It saddened him all the time. It was very tough for him. He really wondered if anyone, aside from a very small faction of the scene, were any kind of real alternative society at all! I thought it was definitely an alternative society then, and I still think so now. But then again, a lot of things would make an observer looking in totally disagree with me. Like everything else, it basically comes down to what a certain individual is going to do with it—with that punk rock ethic.

After joining Madhouse/Strange Boutique, one of your best stories involves Geordie from Killing Joke. What made that time period special?

I don’t know if any of you really know this, but I must be one of a very minute number of the luckiest punk musicians that has actually had a very uplifting, incredible life through the various bands he’s been in. Not only did I work at one of the country’s top underground, cutting-edge clubs of all time, Nightclub 9:30 in Washington DC, I have also been in two very special bands that have allowed me to play with all of my peers for each band genre that I was in at the time and to excel at the music genre, whatever it was. In Beefeater, we were honored to play with such bands as Rites of Spring, DOA, NOFX, Agnostic Front, the Dickies, Scream, SSD, Dag Nasty, 7 Seconds, Bad Brains, Big Black, the Necros, HR, etc. As my run with hardcore came to its end in 1986, I was, in about four hours after leaving Beefeater, already enlisted in a now upcoming post-punk band—one more accessible than the hardcore scene and appealing to a more eclectic adult dance audience

Strange Boutique emerged out of the ashes of Madhouse, fronted by lead vocalist Monica Richards, formerly of D.C. punk band Hate from Ignorance. As my style was now changing to the heavily Euro pop indie sound, I was getting influences from the likes of the Cocteau Twins, the Damned, Killing Joke, PiL, Punishment of Luxury, the Slits, and Magazine. Unbeknown to me at the time, I would soon be touring with the likes of some of them as well. Fucking incredible, fuck, you couldn’t make this shit up: this is a dream, right? Whaddya mean we are heading to England? For real? In fact, on a support gig with Killing Joke in England I was approached by one of my idols, the all-time European guitar great Geordie, during a sound check. He actually got to check me out and see what I was really about. I passed him in the corridor of the club, and he goes, “Mate you’re a pretty good guitar player.” I then asked, “Hey, would you put that down in writing for me?” He quickly responded in that heavy English accent, “No!” [laughing]. Always magical when one of the greats takes even a little time out for the little guy. One of my best days of all time. Will never forget it. Wow.

For me, it makes sense, musically, since people like James Stevenson from Chelsea joined Gene Loves Jezebel, and New Model Army can be linked to the Crass scene. But why did Strange Boutique become such a good fit for you?

Strange Boutique took a real fucking gamble on me, really. Here I was this totally out of control hardcore guitarist, chains dangling from belts and shit, and they just took me in to play this new form of music I was coming into—dark, pop, heavy dance groove shit. After some early experimentation, we soon were labeled Goth. Now, at the time I was really growing. Unlike the days of Beefeater, I was now fully exploring new territories—new amps, effects (which I had never even considered ever using before in Beefeater), the now signature classic trademark Ovation acoustic/electric 12-string, which I learned to also send through the Marshall and JC-120 to run a solo thru once in awhile with full-on lead distortion. Strange Boutique was my time, and I was definitely ready. Probably to this date, even though my Blaxmyth did make a dent, Strange Boutique was and always will be the best band I have ever been in, period, fucking F.