Scam zine’s Erick Lyle

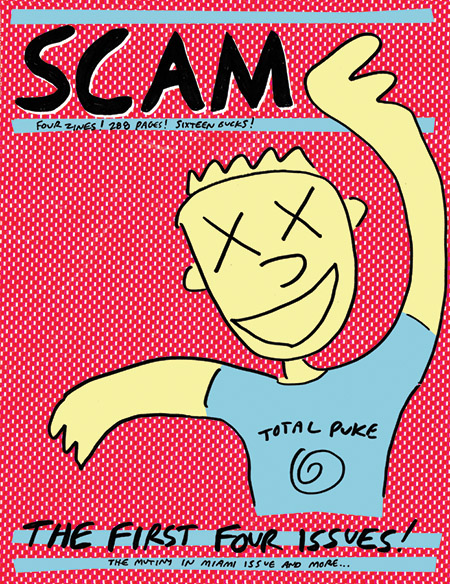

Since the early ’90s Erica Dawn Lyle has published Scam zine and played in tons of great bands, including Chickenhead, Allergic To Bullshit, The Horrible Odds, Onion Flavored Rings, and Black Rainbow. In recent years she has parlayed Scam and his many other DIY zine projects into a bona fide writing career of sorts, with one book under her belt (On the Lower Frequencies on Soft Skull Press), another in the works, a number of articles in the San Francisco Bay Guardian, and just this month a bound, full-sized reprint of the first four issues Scam!

Interview by Arwen Curry. Appeared in MRR #311, April 2009

Do you remember the first time you saw something that was like a zine or a pamphlet, a noncommercial, underground piece of writing? What did it look like to you at the time?

I thought from a pretty young age that I would become a writer. I enjoyed writing in school even really early on. Like when I was seven or eight, I was always writing stories, but there was a period in my early teens when I was running away from home a lot, having a lot of trouble with parents, and randomly living on the streets here and there. I started to fail out of school, which hadn’t been a problem before, and I started to think that I’d fucked up my life in some way where I wasn’t going to be able to become a writer anymore—because I wasn’t going to finish school, and, that I would need to go to college to “become a writer.” But then somehow I happened upon a Hunter S. Thompson book that I cheerfully shoplifted from the mall, and I was reading this lunatic tale of crime and drugs and stuff, and realized, “Oh, OK, I actually already am a writer. This is awesome.”

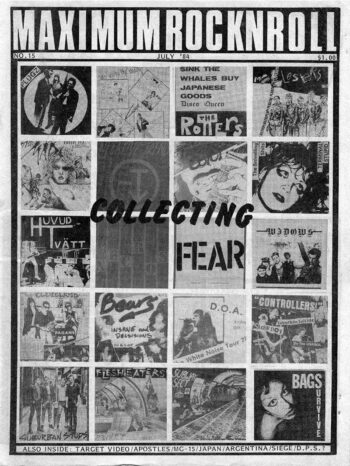

That was before I was a punk rocker. It wasn’t until a couple of years later that I was into punk rock and seeing zines. There weren’t a lot of zines coming out of South Florida, but finding a Maximum Rocknroll actually was a pretty big deal, and we found it in a chain store, so that’s something to consider—that sometimes in a small town you gotta find the punk rock in a chain store. This was probably 1988, and me and my best friend Buddha thought that we were among the last remaining punks on earth because there were no other punks in South Florida, and all the bands that we liked, like Black Flag, the Descendents, Hüsker Dü, the Minutemen, they had just broken up right before we got into punk.

We had seen the Circle Jerks, and 7 Seconds, but somehow something was missing, so when we found this Maximum Rocknroll, we were like, “Holy shit, this magazine is full of demo tapes; there’s a whole world out there,” so that was a pretty big deal. But the first zine I saw that really influenced me was a couple years later, probably in 1990, when I left my parents’ house for good and ended up at the Ft. Lauderdale Punk House. My roommate Chuck Loose was making a zine called Get Loose, and it was all about scamming, dumpster diving, bumming around town, graffiti, and stuff, and I was like, “Hmm, OK, this is cool. I can do this.”

When you were a kid did you have books in the house? Did your parents encourage reading, or was it something that came to you more in school?

My parents did encourage reading. They read to me out of the encyclopedia every night before I went to bed. They read to me about the presidents, I remember, pre-kindergarten. I don’t know what was up with that, but I do remember getting to school and in first grade and we all had to read in front of the class. I knew so much more about reading than everybody else in the class that I was completely embarrassed, and I pretended not to know how to read as well for a while because I could tell early on that if you knew things, you were gonna be ostracized, and I probably even knew what that word meant then, so it was a bad scene. At the end of the year I won some “Most Improved Reader” award because I’d been lying the whole time.

But when I saw Get Loose, I was like, “Oh, we can just publish right now! Ourselves!” That didn’t seem like something possible with Maximum Rocknroll—that was some magazine that took place in California that we got in a chain store. Up until that point I was still writing pretty avidly about my experiences, but didn’t know hot to get stuff out. I did have this weird gig at a college newspaper. When I first got kicked out of my folks’ house for good and I was living on the beach in my hometown, all the kids on the Florida Atlantic University newspaper had quit because of some disagreement with the administration and then, off-campus, they had started an independent version of the school paper that they were publishing. They were hiring people who weren’t students. I went in there and got a gig as the music columnist and political columnist, even though I hadn’t even graduated from high school and I was seventeen, homeless, and living on the sand. I got paid some crazy amount, like eight dollars a story, but it was money, and that was encouragement.

I wrote three columns about the Gulf, and when I went to write the fourth one, the editor was like, “Hey, man, you can’t really write about the war again this week, it’s a real bummer,” and I lost my column. I had thought that I was about to be part of the mass student uprising that would rival the Vietnam era, but I could see that it was sadly a different generation that I’d been born into.

When you first decided to do an issue of your own zine, how did you go about it? How did you pay for it?

Buddha and I decided that we would start a zine. We wanted to book shows, do a band, do a label, do a zine…is there some other DIY things you can possibly do? Write a scene report? Make flyers?

We started working on the zine really avidly to document the life of petty crime that we were living there in Ft. Lauderdale, like dumpstering and pasting up anti-Gulf War flyers around town, stealing stuff, just whatever, having fun. Then Buddha kind of dropped out of it. He had wanted to call it Reagan or Scam, and Scam seemed really appropriate, since that’s what we were doing, and it kind of defined the theme a little more too. I ended up just spending a lot of time sitting and working on it. It was real fun just cutting and pasting and stuff, and Chuck stole all his photocopies from Office Depot, which was then kind of a new thing, so that’s what we started doing. The dishonor system. My mom worked for Office Depot for seventeen years and they totally fucked her over. She was completely shit on every second of her life there, so it felt nice to steal from Office Depot. Still does.

With this first issue, did you think of it as a contributor zine or did you see your writing being prominent? What was the format going to be?

We felt like we had a really cool scene in a small town that people wouldn’t come to—no one wants to go to the bottom of Florida because you have to go all the way back out. You can’t get bands to come, and I think we had a lot of pride, like “We’re having a great time down here…” and we wanted to get that out. So there was a little bit of a chip on our shoulder too, like, “Fuck everybody else, South Florida rules!” It was more just about the lifestyle and trying to get that out. We were reading Abbie Hoffman books at that time and reheating dumpstered food and serving it to homeless guys at the library. We were really strange people.

Was Chickenhead going on at this time?

Yes, but we were an imaginary band. We hadn’t actually played any music yet, but it was all planned out; it was going to happen. It was hard to get everybody in the same room, but when we finally did play the first time, we played this party in south Miami, and we only had three songs, Buddha and me had written the songs with a drum machine, and then we asked Chuck to sing. The drum machine was called “Dr. Rhythm.” We played this party, and Chuck broke all his bottles of peanut butter and started rolling around in it, and I was like, “Whoa, this is gonna be a cool band!” I had no idea. He hadn’t told anybody what his plan was, and I was like, “Right on!” We played our set twice.

Did you feel connected to people doing this in other places?

Yeah, because Chuck had booked some shows, he had gotten some bands down there. We did a big Plaid Retina show. We got people’s phone numbers somehow, and I spent a lot of hours drunkenly calling people across the country and trying to convince them that they had to come to play our town. So I was on the phone with Eggplant, or the guys in Christ On A Crutch, or I called Lance Hahn all the time and left messages—never even got to talk to him. I was like, “You gotta come out here! We’re gonna do a comp record! Can you be on it? We’re gonna do everything—a comp, a label, a zine!” That’s how we met a lot of people in the Bay Area, like Green Day and Monsula—just calling people up and being like, “You gotta come to Florida. Don’t you understand?” None of them came. Well, Christ on a Crutch came. They ruled.

So you already had these roots set, this connection all the way across the country here in the Bay Area—what was the impetus for coming out for the first time?

Joey who drummed in Blatz came out and visited for a while and he played drums in Chickenhead for a little bit. Then he was going to go back to California to come back on tour with his band Jack Acid, so I thought that I would come out here and hang out for a bit, and then get a ride back. That was my plan, but he never told them that was going to happen, so it was a pain in the ass, but that’s what I did. I was really into South Florida and I (incorrectly) thought that it was an easier place in the Bay Area, that people that moved away to the Bay Area were going the easy route. But then a couple of years later, summer 1993 after Chickenhead’s last tour, I was here in the Bay Area and was going to do some big California bike ride, but it fell through. I started hanging out and got really into San Francisco, and I decide to move eventually.

Let me ask you a different type of question still relating to youth: A lot of kids in the punk scene, for whatever reason, don’t get into reading. Maybe they read zines and stuff, but in terms of print, what would you recommend to someone who thinks that they don’t like reading?

You probably gotta read all the Hunter S. Thompson books; The Basketball Diaries; what about Michelle Tea or something? This is a good question for you: has there been a great punk rock novel? I say no; I can’t think of one.

I don’t know. I can’t think of one.

Like Bukowski or something. On the Road. That whole punk rock life hasn’t been novelized in a satisfying way for me.

Me neither. I was thinking also of the books about punk, which for some reason I stay away from for a few years, and then kind of creep up on later.

Please Kill Me is obviously brilliantly conceived, and has become the editorial template for every other kind of cultural history book, because it was so well done. So that one was great, but it’s not a novel. Books about punk, too, sometimes those are pretty sketchy, where you’re like, nuh-uh.

I think that Scam, Cometbus, or Doris, zines that are aspiring to be better written, are good for younger punk rockers. If you’re talking about making a leap, like, “How is literature vital to me? How am I represented in it? Where are the freaks in literature?”—that’s kind of hard. There’s that Lester Bangs book I read when I was a kid.

Yeah, I remember being impressed by his fantasy about James Taylor being pushed off a cliff, thinking, that is so awesome! Can you say that?

Because it’s about rock and roll; it’s about living outside of the system. Being an outlaw, something like that. Everybody reads One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest when they’re a teenager; that was a big mall heist shoplifting book for me. I was like, “Yeah, this is awesome.”

That’s true, and there’s Vonnegut. So your book, On the Lower Frequencies, is a collection of excerpts from Scam magazine, Turd-Filled Donut, and various other writings that you’ve done. It’s not exactly an anthology; it’s a collection.

The book is kind of like one half of the Scam book, it represents what I’ve been doing for the past ten years here in San Francisco: anti-war stuff, anti-gentrification, working on a skid-row newspaper, squatting. All kinds of crime in there, but kind of a more community organizing level in this weird way, and the squatting is prevalent. There’s not the freight-hopping and stuff like that from Miami. That’s all going to come out in another Miami Scam anthology, probably later this year. It will literally be reprinted from the zines.

With On the Lower Frequencies, I made the decision to type things up and to mix up the narrative. I wanted to make this bottom-up sort of history of the past ten years out of this writing, using the primary documents. There are repeating characters throughout, and the reader is able to see what’s happening. It’s a little more show not tell; the reader can put it together in their own mind and see the trajectory of everybody and what we’re working on without me having to sum it all up.

I wanted to reach beyond just the people who read Scam. I think it is vital lost history. I think that thousands of protestors shutting down San Francisco when the war started is a lost piece of history that’s pretty inspirational. I think squatting is obviously an antidote to foreclosures of homes, the current economic crisis. So, I felt like I wanted to have the book in typeface, to be as legible as possible so that the ideas could come across. Most people get that and seem to be into it. I’ve never been satisfied with the way that Scam looked entirely. I don’t like it that you can’t read it and that it cuts off on the xerox edges and that it’s illegible. And when the stories get longer, they take up too much space handwritten. They literally would be eight xerox pages, and it becomes two typed pages, you know?

How was it to work with Soft Skull, your publisher? And how do you feel about the book and how it came out?

I love the way it turned out. I had full control over everything. Soft Skull served as a vital sounding board for ideas, but ultimately I was able to have a lot of freedom. For instance, I designed the cover of the book. I didn’t actually construct it, but I came up with the plan and laid it out. An author never chooses their cover when they’re working with a more mainstream press. An author seldom has a choice of their title, things like that. So I have a lot of respect for Richard Nash at Soft Skull. I think he’s a great editor and publisher. I have another book with them coming out later this year, hopefully.

You’ve been touring with this book quite a bit. You took it around the East Coast and the West Coast and back…

Midwest, South, Canada. In bigger towns where I think there’s a stronger independent bookstore scene, the crowds were really diverse age-wise, or not entirely punk rockers. I’m excited about that. Seattle was like that. I really love to go see people talk and read, but it’s a difficult thing for me to do, to stand up there and do that, so it was a challenge to try to get into a place where I could just go have a conversation with strangers about stuff I’m into. I think everybody would be well served by trying to figure out how to get themselves across in public to small groups of people. It’s different from the band tour because it’s so easy. It’s like, the shows are at seven instead of midnight, and no one is blacked-out drunk when you’re reading, ever. It’s all over in an hour, hour and a half, instead of like hours and hours of stuff, and you can just go hang out the rest of the night. It’s real chill, you know?

In On the Lower Frequencies, the action is seen as it’s happening, as opposed to looking backward. And it’s not just your perspective—it’s a chronicle of a community engaged in acts of creative resistance against gentrification, the wars, globalization, etc. There are enough interview segments and pieces included from other people that it does read like a collection of voices with a strong editorial slant on your side. In terms of the struggles that are being talked about in the book, what is the role of the writer?

In this case, with the book, I’m trying to collect a history of a community’s efforts over a period of time, in order to make sure that those efforts aren’t lost completely, and so that we can have room to reflect on what’s happened, to encourage debate amongst ourselves about what worked, what we were trying. Or even about whether that history is valid, but just to keep it alive. Because other people that were involved certainly might have their own perspectives, and that’s welcome as well. So I put it out there for our own benefit and also for the benefit of folks who aren’t involved, for future readers, or even for distantly future readers, because there are tactics and ideas in here.

You mentioned that the book is against a lot of things, but also the book is for a lot of things. That’s actually one of the main things that we as a community—the people who were working on these protests together—were talking about, was the idea that we should be fighting for what we’re for and not what we’re against. It’s something that I come to again and again in the book—these sort of lost utopian moments, where we’ll have some squat in downtown San Francisco for three months, where we’re serving free food and having these amazing shows, and actually living the life we want on Earth for these ephemeral brief moments, and I think that writing and literature, whether it’s fiction or nonfiction, creates a space where those ideas that are sometimes too fragile to survive in the light of day can live on dormant, like a virus, in print, waiting for their moment to come back.

So that’s important, and also, as a weird history freak, it’s a way to talk about the texture of what life was like in this city during these historical eras, so if people are trying to put it together later, or research way down the road, they can kind of have a more satisfying description, you know? Because I do research all the time, and I’ll try to research like, what was the protest like in 1991 when the war started and people shut down the Bay Bridge? What did that feel like? And there will be all these pamphlets about that time where it’s like, “Last night we went and took over the bridge, because this fuckin’ fascist war has gotta be stopped! These imperialists are trying to destroy our way of life! They’re trying to destroy Iraq! This is not gonna be allowed!” and you’re like, “Dude, what was it like when you took over the bridge? You’re not really going to tell me? I can’t believe it!” So, my message to the reader of this, my rant, a side rant, is: if you’re writing history, use descriptive words. Describe what happened. Say how many people were there. What was the weather like? What did it feel like? What did you do, in what order? These things are going to be really important later. We know that the war is stupid and imperialist. What was it like? So, that’s part of why I did this too.

In On the Lower Frequencies and in Scam, the actual people that were involved have a voice and come to life, and it brings the experiences to life, it makes them human, it makes them possible, as opposed to reading rhetoric or rant. And this is something about literature in general, and about books—when ideas are brought to life through the experiences of real people, they mean something to readers.

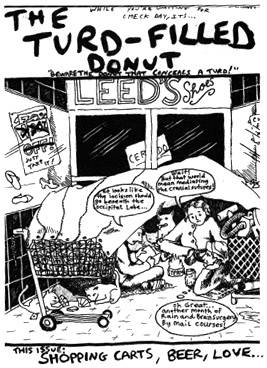

Well, you’re right, and this goes back to the initial experience of discovering Get Loose and being like, “This is something I can do.” I’ve definitely wanted to create that sense with Scam and The Turd-Filled Donut and now this book, that the kinds of things I highlight are ordinary folks just deciding to carry out an action. It’s not like they answered a flyer from International ANSWER and went out to the protest march; it’s like, “We saw an empty lot and wanted to turn it into a garden and we did.” That’s definitely part of the point, is that I want people to feel that they can do whatever they want.

A lot of your work with The Turd-Filled Donut, in particular, is very conscious of the press, of the role and the function of the newspaper. The Turd-Filled Donut is a pretty blatant satire in a lot of ways of the San Francisco Chronicle. Now the whole thing is changing. I think it was the New Yorker that reported that many cities are not going to have a daily newspaper relatively soon. I’m curious to hear what you think the function of the daily newspaper is, what it should be.

A lot of your work with The Turd-Filled Donut, in particular, is very conscious of the press, of the role and the function of the newspaper. The Turd-Filled Donut is a pretty blatant satire in a lot of ways of the San Francisco Chronicle. Now the whole thing is changing. I think it was the New Yorker that reported that many cities are not going to have a daily newspaper relatively soon. I’m curious to hear what you think the function of the daily newspaper is, what it should be.

It’s a good question. Well, just for the reader of this interview: The Turd-Filled Donut was a neighborhood newspaper that me and my friend Ivy started when we moved back to San Francisco in late ’97, and we were living in welfare hotels on Sixth Street, which is kind of the skid row of SF. We wanted to put out a paper that documented some of the real community that existed there, and also some of the protest activity that did take place. Tenants’ rights kind of things. We would steal newspaper boxes, repaint them, and put them out on the street with the paper in them. It was available for free in various social services agencies and hotel lobbies and stuff, so it was very much an attempt to reach as many people as possible. It might start a conversation or spread some news, to put out a different idea to the reader that they are part of a neighborhood. We were very conscious of the press, and I was pretty conscious about not printing articles that were unfair or fake or hearsay. I really wanted to be able to back if up if we had some kind of news story. I’d give the other side a chance to respond. It was almost by the book in a certain way, even though it had this crazy voice.

And Ivy went and interviewed the mayor, Willie Brown.

Right. We didn’t present him in the best possible light, but it was all his quotes. That paper wouldn’t have made sense if there weren’t a context of community, of being in a city where there are defined neighborhoods. It was about taking people that aren’t normally part of the debate and trying to give them a voice, because it’s understood that there is this public place where we should be able to talk with everybody else. So what you’re talking about when you’re losing newspapers is a decline of that public space. Even though the newspapers are a for-profit concern, there’s a democratic ideal behind it, that they’re part of the place where everybody’s going to be represented in some way. Even though we know that’s not really true, it’s a framework to even rebel against, you know? How are you going to rebel against that if it doesn’t exist? It’s a good question.

I don’t think it’s good for newspapers to disappear. Not just because I like them and the way they feel and crinkle. Not just because I enjoy the familiarity of the style of writing, even though it’s full of fucking total lies and garbage. Not just because of my daily ritual, not just all that. I think it’s because this country’s misinformed about everything factually, and I have a feeling that the vast majority of the public is actually really interested in being deceived. Maybe even more so in a place like San Francisco, where there are so many alternative news sources, I think that people are going to seek more of the news that they want to hear. So on the one hand there’s this paradigm of the newspaper that we’ve been rebelling against all this time because our voices are shut out of it and we think it’s bullshit, but if people are going to their favorite blog to find out what the news is, and it’s not even factual, whether it’s far right or far left, what are we left with there? There’s no ground zero to work from.

Self-selecting?

Self-selecting. People on the left don’t think that’s a problem because they automatically assume that their facts are more correct, but we’re going to see in the Obama times that they’re not. Electric cars are not going to save us. We’re not going to make friends with the people in Afghanistan who want to blow us up by just seeming nicer than Bush. These are fuckin’ fictional narratives that we’re trying to embrace to feel better about our country and ourselves. But what about the right? There’s this vast population of people that think that the world is 10,000 years old, and that’s just what they believe. So we’ve been saying that they’re crazy and this is what we’re up against all this time. Well, on the left there are also things that are totally lunatic? These false narratives that people on the left are embracing are actually really harmful—especially when they’re used to, say, justify escalating a war in Afghanistan. And I just think that as there’s less and less center of news, down the road, people are going to be more and more misinformed, and it’s going to increase polarization.

Part of it, too, is that the reporters of the newspapers are accountable to their editors, and the editors to some degree are accountable to the public. But when you’re talking about bloggers, what is their accountability? Nobody can fire them, nobody’s editing them.

Or, are they even real? Is this just a persona? There was a guy who was doing a hoax McCain blog, all election-year, claiming to work for their campaign and just putting out all these total lies about McCain as if he was on their side, just like satires. It sounds like a real fun thing to do, but people are reprinting it and it becomes news, so I don’t know.

So, unfortunately, it looks like you’ll be moving out of your cool old 1905 office building downtown. Do you want to talk about your noir office and your love of noir fiction?

You’re referring to my office on Market St. in a pre-earthquake San Francisco building that has this rad black-and-white film kind of aesthetic to it. It’s like some kind of Sam Spade situation, and it is from Sam Spade’s era. Noir fiction is kind of like muckraking fiction; it’s based on the idea that there is a hidden truth behind the façade of daily life, so that the protagonist is either trying to find that truth or is suddenly brutally made aware of it. But there’s something deeper that’s going on. I think that relates to a search for history or my love of those kind of secret facts, and also it’s about finding yourself represented in print, like we’ve talked about already a little bit. Because in the noir fiction you’re more likely to see criminals represented, and the down and out side of life, and I feel like I recognize the places of the noir fiction a little bit more.

I’m from Miami, which is one of the city locations in the noir canon. Miami and LA are really huge in detective novels because they are places with these façades of sunshine and endless paradise. Palm trees and cruelty, that’s what we used to call it back home. Underneath, there’s this sordid world of poverty and crime. In a way, On the Lower Frequencies is a little bit of a noir history of the recent times of San Francisco, except that it’s overtly political and idealistic. It’s not that bleak, but it is a look at the underside, a look at history from the skid row.

You do a bit of writing for a living as well; you write book reviews for the weekly paper here. What have you been reading that you can recommend?

I was just writing about the new translation of Roberto Bolaño’s book 2666, in combination with the Chinese exile writer Ma Jian and his book Beijing Coma. I was writing about them together and about this election cycle we just went through. It is a time where we’re looking for some real change, for sure, and as much as I admire the intelligence, temperament, and abilities of Obama as a person, I felt that a lot of the change he was offering up was not really substantial. It was more about tweaking the national storyline in a way so that we can continue to tell ourselves things that are going make us feel good about our country. Ronald Reagan, when he was elected at a time of really low morale, was able to sell the storyline about how America should feel good about itself. And I kind of think that Obama’s brought that back at a time when morale is really low, by selling a different fictional tweak of a way that we can see ourselves as the richest, most powerful country in the world.

And honorable.

And honorable now. Instead of being the richest, most powerful country in the world that can bomb anything we want, we’re going to be this strongest, richest, most powerful country in the world that’s a little bit more friendly, and we’re gonna use a different form of coercion to get what we want, supposedly. But we’re not the richest, most powerful country in the world. The whole world is humoring us because we’re so dangerous, you know? Everybody’s like, “There you go, US, sure you’re still the richest, most powerful in the world, sure; I mean, China owns you and you’re getting your ass kicked in these two guerrilla wars, but you’re still the best!”

I was writing about the idea that we need to actually be prosecuting Bush. We need truth and reconciliation to deal with this era of torture and the total disregard of the constitution. We have to look at the past factually to make a record of it, to tell ourselves the truth about it. That’s not going to make us feel good about it in the same way. But it’s a harder won kind of hope than just to embrace self-delusion. It would feel far more hopeful to really deal with these things truthfully and to say, “That’s not what we’re going to do anymore.” That’s what’s so necessary, and as long as we put that off, things aren’t really going to change. How that relates to Bolaño and Ma Jian is that I just felt they wrote these brilliant books that were about dealing with the truth of atrocity and really uncomfortable, difficult, grizzly truth—political truth. If political leaders and journalists are going to collude to create these storylines that are fictional, then the task of true memory is going to have to fall to literature. These foreign writers provide this really hopeful example to me. This is really incredible, this is against all odds, here is somebody really striving for the truth. So I recommend Beijing Coma, 2666. On the noir front, I recommend Ed Bunker, who wrote the classic criminal memoir Educations of a Felon, and the prison novel No Beast So Fierce.

In particular the broadcast news is interested in selling stories that people want to hear. Reading a lot helps you understand how the world is being constructed around you, that people are writing the storylines. People are creating the narrative, and if you can’t recognize that you’re in trouble. We have a natural tendency, if we hear things over and over and over and over again, to believe that they’re true.

And the storyline is also constructed by what sells. That’s part of the book biz. You take the lid off of that, and it’s too depressing to even think about. Actually, someone asked me to write a book that was like a Scam survival book for all the yuppies that are losing their jobs. Someone else is probably going to write that book this year; don’t be surprised. It’s what people want to hear, what’s going on combined with what can sell, and it’s such a cynical mixture, and that’s what we have to slog through to find culture. That’s a drag. At least blogs are free.

Yeah, for now.