Blast From the Past: Gary Floyd

This originally ran in MRR #317, October 2009, that issue is sold out but you can download it here

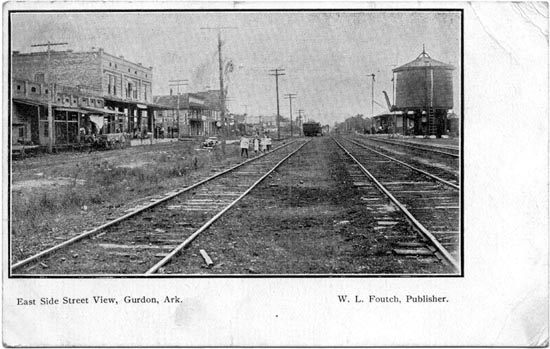

Gurdon, Arkansas

December 11, 1952

9:45 a.m.

I’m born.

My whole family was from this blink-and-miss-it small town in Arkansas. One little clump of stores here and another there. Two railroad tracks running like rough zippers through town. The tracks full of dead men still spooking the town with lanterns. Gurdon, where Jimmy Witherspoon got knocked on the head with the blues. Where bored lumbermen concocted the International Concatenated Order of the Hoo Hoo, with a black cat as their symbol. A joke that became a weird version of the Elks Club. Although my family moved away due to cutbacks in the Missouri Pacific Railroad (which used to belch black smoke in the old twilight), a few things stuck in my head forever.

When the Butlers moved in next door—Cleda and Gene, with young Brenda, and the first cool person I had ever met, Russell Butler. He was probably only sixteen or so, but to me he was ageless and brought out the need to let my “cool seeds” grow. He was an artist, a beatnik who painted pictures of himself in coffins. I knew I had been influenced. Got my cool seeds sown. A taste of being different, and the shape of things to come.

Going to vacation—Bible school—one hot summer, when the humidity could be sliced with a rusty butter knife. The First Baptist Church: a cool breeze in the auditorium, Kool-Aid painting our lips ruby red, and a fragile mound of cookies. They ended the day by playing the old hymn “Just as I Am.” Tears rolled down my face, and I knew I wanted to give my life to Jesus, so I walked down the aisle into the arms of Brother Nelson. I was saved. I was eight.

The Daisy Queen, early 1960s, when people were rumbling and fawning over radios. My mother’s dream—a place to eat where all the tiny town’s teenagers hung out. Male car hops, and a teen side, which was just a big old room with benches. I could watch them dance loose and free. Girls putting on make-up and drinking Cokes, boys flirting with the big hair girls and dancing too. Me looking, wondering if I could be the boyfriend someday.

Soon, the family was all packed up and moved to Palestine, Texas. New things to freak out about. A new school of hardcore rednecks…pretty eyeliner girls and strapping boys in the shower haze that I remember to this very day.

As my life shifted from Arkansas across the pancake batter Red River to thick piney woods Texas, lyrics were being implanted deep in me. I didn’t know it, but they were becoming a permanent part of my spleen.

My grandfather was poor, poor, poor. He and my grandmother (my father’s parents) were saved by the railroad, which offered a steady job to the lean and hungry people of the time, when some headed west to pick fruit in the bowels of Oregon and some stayed and ate dust for years. My father got a job at the almighty railroad as well. He worked there all his life and left the job only to join the Army and fight in World War II.

He was in Japan after the big bombs fell, loosening the roiling clouds of death that turned entire cities into gutted wastelands. He used to tell me about the shrines people had in their houses. I asked, “How did you see what was in their houses?” He told me, without lingering shame, “We’d just go in and look around.” I asked, “Did you knock?” He laughed deep down and said, “No, that’s not how it worked.” I knew then, right there, there would be no army for me. Fuck that shit.

He came right back to those sturdy engines, those trains, as if the bombs never fell. It was expected of me to do the same.

He told me about going to work for the railroad—the honest pay and hard work, a kind of untrammeled American dream people wanted to believe in even as Vietnam squandered it with napalm and Nixon. Even as I said, yes, grandpa, I could, I knew I would never do it. I knew I wasn’t meant to look down those bleak black tracks and feel like home was beneath them. I couldn’t even pretend to love the heft and bulk, or history, of trains, no matter how many times Elvis purred “Sixteen coaches long…got my baby and gone.”

I was going to move to Austin, that vortex in the armpit of Texas where the liberals, freaks, rockers, commies, and rednecks all converged, and live with my old high school buddy.

But I was drafted in 1972. I registered as a conscientious objector due to my girlfriend’s liberal mother. She turned me onto the best book of my life, The Conscientious Objector’s Handbook, a Quaker publication. It told you all the things that you should expect and indeed, did happen to me. The lies and misinformation the government would hand you to trip you up and then be able to send your ass to war.

My low lottery number of 54 picked during Nixon’s time sent me to Jefferson Davis Hospital in Houston, Texas. The Janitorial Department: mops and brooms instead of guns and blood. Instead of sergeants and drill instructors, I had Mrs. Harper and Mrs. Green. I also moved to the biggest city in Texas, to the Montrose area of town, where the gay bars stretched down Westheimer. The first place I ever saw gay men walking around unashamed and OUT. It was also the summer David Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust came out.

Some things good, and some things bad, stirred those times. Both were going to change my life forever. Being a janitor and queer, and singing about both, was again being stored in the “someday” part of my heart.

I came out during this time and hung out with the worst gay people in the world at Art Wrind’s Silver Dollar Saloon, a restaurant of sorts. I usually hit the place around ten pm. My job shift was a lucky one, 1pm till 9 at night, so I’d run home, change clothes, and hit the street around the Silver Dollar. I thought that this is what being gay was—the sleazy hustler and hardcore drug life. My real first shock was sitting in a bright blue booth, when a young man slid in across from me with an older guy beside him. It turns out they were father and son, a real father and son. My eyes were open wide as the dad pulled out an old time syringe with the rubber bulb on the end and fixed up a spoonful of speed. As he was shooting the boy (no more than fifteen or sixteen, I swear he hardly had fuzz on his lip), he told him, “You gotta come home with some money tonight, kid. Rent’s due and you need to bring home all you can make. Be careful.” The needle came out. “Now go.” In a flash, they were both gone. Nearly 40 years later, I see them, though. Right there in the booth with vinyl seating the color of veins trickling down a forearm. I stored that little memory away. That’s Montrose in 1972.

San Francisco, 1978.

Just seeing the Sex Pistols gave me a little “big headedness” with the one or two people I knew who had even heard of them. You know, imagine seeing the gods of punk with 3,000 bewildered people. My roommate and I strolled into Winterland in SF after buying our $5 tickets. I was trying really hard to be cool, but this was almost an overload. My memory is rather distorted by time and a certain dream-like sensation that immersed me. The Sex Pistols: Johnny Rotten’s harrowing, pimply, and scowling face; Sid’s carved and beaten chest.

Walking in, I was soon elbow room with hundreds of other punks—beautiful, eerie, weird, and some a little cutthroat scary. I loved it, though. I had this Dee Dee Ramone boyish hair cut, but made a quick note to “cut hair tomorrow.” To me, who had never set foot in Winterland, the place seemed ominous and huge, and people walked in a big circle outside the auditorium. Literally, they just walked in a big circle before going in to see the band. Now, I know they were just “being seen”—like unleashing an impromptu fashion show and “I’m Here” statement. I felt so uncool, though, being in a blue jean jacket with that long hair weighing me down. I don’t even think I drank a single beer because I had no money, just lint in my scraggly pockets. Back then, in that big room, I didn’t care.

I could see the misty-lighted stage—the Nuns were chewing through the last songs of their set. These people were great because they looked so severe and real, and they sounded louder than bombs. I made a mental note to “start band at once,” and just stood there with my mouth open, watching the likes of skinny Alejandro Escovedo in his dire punk glory. Seeing the Nuns makes me special…right?

Then the Avengers descended. The pure, fierce, and buzzcut goddess of the world of punk (except for England’s infamous Catwoman) was there on stage. Penelope Houston, the most beautiful woman in the damaged world. As she hopped and jumped across the stage in blurry pandemonium, I saw him to the side of the stage—Sid Vicious. Laughing and watching the band, swigging on a big bottle of beer. He was there. My hair felt a mile long. Note to self, “fuck up your hair tomorrow.”

Then the Sex Pistols sprawled across the stage and played. It was wonderful and wicked. I was hearing the songs that had penetrated my head while being played 10,000 times at home. Now, I hear the horror tales, what was really going on with them in the trek across vast dumb-ass America, but I didn’t know any of that then. It was like a bible-thumper seeing Jesus—or a Hare Krishna sitting down next to Krishna himself.

Life just changed, quick as a coin flip. I was brought back to reality by my roommate telling me his lover was going to be home after being away on a business trip. They wanted to be alone. So, he simply said, “Here’s $10, see you tomorrow.” Now, Palo Alto and San Francisco are at least an hour or so apart, and the bus ride is long. I was being left to the teeth of the city. Quickly, I made another mental note, “move back to Austin ASAP.” I spent the night in a very bizarre SM club—Mr. B’s Back Room. Not really where I wanted to be after the life-changing time I had spent at the gig, but I guess it made sense. A long hallway led to a dark, big, smelly backroom packed with every type of sexual dream or nightmare. Take your pick. You couldn’t see the face of the person next to you (not that you wanted to, either). After awhile, the little blue light bulb in the corner enabled me to see good enough in the void to give at least five or six blow jobs to no-faced strangers before finding a bench in the corner and going to sleep. Oh, what a night. From the Sex Pistols to the sex pistols…distressed, down’n’out, and dangling in the dark.

Soon, I was going to be back in Texas, though. God was looking out for me. I had seen the twin engines of punk, Penelope Houston and Sid Vicious, in the same throttled night. I had a lot of filthy sex, and thoughts of Austin were in my head.

Austin, 1979

When I first met Buxf (like Buff—the x is silent…this is what he always said) and Glen, I never knew they would become such huge parts of my whole life. I had been back in Austin a very short time when my friend Lynn introduced me to a new guy in town. His name was Dan, and he worked at a high-end beauty salon. He had worked at Sassoon’s in San Francisco and had only lived in Austin a few months. He was the most smart-mouthed and incisively intelligent person I had ever met. He loved to bleach my hair, then put Crazy Color on it. OK, this was 1979, Austin, Texas. State government yahoos and frat boys in Camaros and Woodstock wanna-bes and leftover cosmic cowboys and me walking around with super-red, sorta Dayglow looking hair jumping off my head. People would almost have wrecks looking at me from their cars. I loved it and was the first person I knew who had this kind of electric hair 30 years ago, when boys aimed for Aerosmith aesthetics. I didn’t have a car, so I got around on the university shuttle bus or the terrible Austin city buses that cut the city in half. Lots of contact with the “normals.” People would say really stupid shit, like, “Is that your real hair color?” I would usually look real serious and say, “Yes.” In response, I would always hear a thick Texas drawl, fighting voice “It is not!” come from their fidgety mouths. Mad…they were mad at me. My flame red hair, and my lack of caring about their ways of living and dying, brought out some emotion—well, searing hate—in them. Again, I loved it, the trigger effect.

Me, Lynn, and Dan had heard of Raul’s and could not wait to go there. The first night I ventured in the bleak bar, The Skunks were playing with the Violators. One fashion I always liked a lot was the “Stained Look,” a light colored shirt and double knit pants. The punks always added some huge, nasty stain on the shirt, like brown cake frosting, or just dirt and water. They’d let it dry into muck, and it looked great, just foul and nasty. The red hair, or white, or some unnatural, mutant color, all looked great. I loved the band and the atmosphere of the graffiti-bitten small club. I went back nightly, trying to soak up the seediness. Dan and Lynn were not so into it, but I was and made friends pretty fast. Chuck and his brother Manolo Lopez, the guys from the Next, and a funny, nutty guy named Barry all knew I was gay, but they also know I was real, not some nighttime poseur, and I was good for a laugh—we all were. I liked to give a beer bottle a quick break and cut my arms now and then, like some redneck Sid Vicious. The attention was great but waking up the next day with a bad hangover and my bloody arm stuck to a friend’s filthy carpet got old pretty fast.

I started telling everyone I had a band too—The Dicks—and we were getting ready to play. Of course, it was a lie. I had no band, but it made no difference. Me and a few friends would make posters announcing:

“The Dicks

playing at the

New Mars Club

1313 Parkway

First 10 people who bring a gun get free drinks all night”

We’d make up some other names of bands (and, of course, there was no New Mars Club or no 1313 Parkway) and put the posters all over the place. I did this for at least a year before I ever met the other guys in the band. My idea was “fuck everybody—I should have a band.” So, walking into Raul’s one night, already drunk, I noticed two new faces. These guys, Glen Taylor and Buxf Parrott, looked real mean, more like freshly released pockmarked prisoners than punk rockers. I found out later they had been there a few times and seen me. Buxf said they called me Alfred E. Newman! The very idea…not that Mad comics wasn’t punk rock, before three chords and the truth garage bands. I walked right up to them, and we all started talking. They lived south, in San Antonio, but were looking for any excuse to move to Austin. I told them I had a band called the Dicks, but I was the only member, so would they like to join? Without even blinking, they said yes! Buxf played bass like a ratfink and Glen played shrapnel guitar. But we needed a drummer—then we’d have a band. At last, like the Germs sang, we were “forming”—the band I had been telling people about and crudely announcing to the stagnant city for over a year. I jerked my head up high, drank about 20 more lousy beers, and noticed these two were keeping up, even out-drinking me. Yes, we had the band at last…The Dicks were ready to come.

You can pick up Gary Floyd’s new book Please Bee Nice here