Blast From the Past: GB Jones

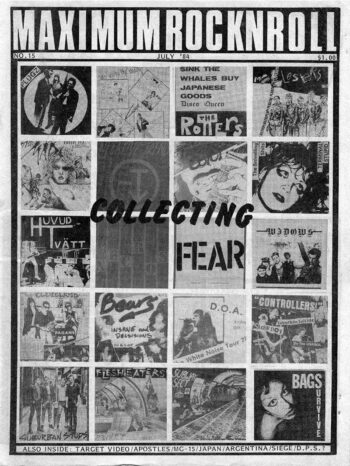

This originally ran in MRR #317, October 2009, the Queer issue. That issue is sold out but you can download it here

“G.B. Jones has an uneasy fascination with authority and uses her gender and sexual preference to exploit fantasies of rock & roll, sex, groupies, booze, drugs, money, leather, torn jeans, motorcycles and stardom as an all out assault against values that would strive for assimilation of queer culture into the mainstream. She’s every queer girl and boy’s hero, whether you want her to be or not. Believe it or don’t, she is looking out for every queer’s best interests.”

Arnold J Kemp

G.B. Jones is an artist, a filmmaker, a musician, a writer and publisher of zines. She has been trying to reshape culture since the early ’80s, in many different mediums. JDs, her zine created with Bruce La Bruce challenged so-called alternative cultures to really be alternative; to open it up in terms of gender roles, sexuality, and identity. With Double Bill, created with Caroline Azar, Jena von Brücker, Johnny Noxzema and Rex, she questioned the acceptance of William Burroughs as a queer icon, reminding readers of his misogyny. In the early ’80s she joined the synth-punk band Bunny and the Lakers. In ’85 Jones formed the infamous Fifth Column, whose early ’90s single on K, All Women are Bitches was a defining classic of feminist punk, and a Riot Grrrl anthem. GB is perhaps best known for her film work and has directed and appeared in a number of underground films. In 1990, the two JDs editors held JDs movie nights in London, Toronto, Montreal and San Francisco, showing their no budget films made on Super 8 mm film. The Troublemakers premiered at this time and proved influential, although rarely screened afterwards till the mid ’00s. She starred in No Skin Off My Ass in 1991. Her best-known work from this period is perhaps The Yo-Yo Gang, released in 1992, a 30-minute exploitation movie about girl gangs. This interview focuses on the just-released ten-year Super 8 epic, the mythical Lollipop Generation. Interview by Anonymous Boy

MRR: Do you remember when you first got the idea for the storyline for The Lollipop Generation, and what was happening in your life at that time?

G.B. Jones: It was thirteen years ago, in the ’90s and thirteen years is a long time…

MRR: When was the oldest piece of footage in the movie shot, and when was the most the most recent?

The oldest footage was shot in the very early ’90s, during tours with Fifth Column, before I had even thought of making The Lollipop Generation. I knew I would use it for something, someday, but in the beginning I was just filming images out of the window of the tour van that I wanted to remember. The most recent scene that was filmed was with Andrew Cecil at Jarvis Collegiate, which is the school they used in the original Degrassi High television show. We filmed that scene in September of this year.

MRR: Of the following aspects of filmmaking, which would you say you prefer most: writing, shooting, working with the actors, working with the animal actors, editing, or post-production work?

The writing and shooting and working with the actors is all one thing. On the day we’re shooting we’re figuring out what to do, writing the scene as we go along. The actor is writing the scene as he or she decides how to play the scene, and I’m writing it as I decide how to film it, and it’s really all about what happens at that time, in that location, and what occurs in front of the camera. And that’s exciting. With the dogs, Batgirl and Big Ethel, it was different, but both of them loved being in front of the camera. Every time we would take a camera out they would get so excited, they always had fun so that always made it fun for us too. They loved being movie stars. Editing and post-production is where everything you’ve done gets re-contextualized into the larger framework. You get to watch the scenes with music and hear the voices and see it all come together. You couldn’t pick any one part over another because it’s all so great. But I think the best part is going to the theatre to see it after it’s done.

MRR: Who are some of the people who have been most helpful in the making of The Lollipop Generation?

A lot of people helped make this movie and it would never have got finished if it wasn’t for them. From the beginning Jena von Brücker has helped me with everything. Even though she hated acting in the movie, she helped in every way to make it. Kids On TV did a benefit for the movie that made it possible for me to finish filming it and if it wasn’t for them, I couldn’t have done it either. Scott Berry at Images Festival did everything possible to make sure I could finish the movie and helped me in so many ways, he’s really responsible for the film getting finally finished. All the actors and all the musicians who wrote songs for the movie were all so fabulous, I really wanted to finish the film for them so people could see how great they all are.

MRR: As with your previous films such as The Troublemakers and The Yo-Yo Gang, and the film you collaborated on, No Skin Off My Ass, some of The Lollipop Generation looks almost like a silent film except with voiceovers dubbed in later. In certain ways it reminds me of the Godzilla movies I loved as a little kid, but in other ways it reminds me of the old silent movies that I never saw until film-study class in college. Is that irritating to you?

Whatever you see in the movie, if it reminds you of movies you saw and loved as a kid, then that’s what’s yours to appreciate in the experience of watching it. That’s all part of watching movies. It’s always something different for everyone, each person sees something different and that’s what so good about watching movies. Even though it’s a form of mass communication, it’s still different for every person. The Lollipop Generation, unlike the earlier movies, includes videotape, which has sync-sound recorded on location, so that’s something really new and it was great to be able to work with it. It’s great to mix it up with the Super 8, and see the difference between them both. You’re right, the first movie, The Troublemakers is kind of like a silent movie, and with each new one it’s like a progression through the decades of film history in a way. Not Hollywood movie history, but home movie history. Now that videotape is a part of it, it’s kind of like they’ve reached the ’70s, when people started making home movies on video. And one day my movies will probably even catch up to today.

MRR: Do you think of your films as within the genre called queer experimental film?

No, no, no. I mean, I think some people don’t really get what we’re doing, so they try to stick a label on us, to try to define and limit us. Some people call it experimental film, some people call it documentary filmmaking, other people call it “New Queer Cinema.” But we’re going beyond the borders they’re trying to impose on us. It is an experiment. It’s an experiment every time I try to make a movie,’cause we’re trying to do things differently, differently than it’s been done before. It’s an experiment with underground stars and songs, from an underground scene.

MRR: Do you see any similarities between the character Jena Von Brücker plays in The Yo-Yo Gang and the character Jane Danger plays in The Lollipop Generation?

Do you?

MRR: Yeah, both seem pretty tough to me, but with an inner soft side, if that makes any sense.

Really? It’s so amazing how Jena could create a character that’s so different from the role she played in The Yo-Yo Gang. She was so tough and mean in that movie, but in The Lollipop Generation her character Georgie is so sweet and innocent. She can be a brat, too, which she has to be to survive on the streets, but I think Jena really makes each role so different that it’s hard to remember it’s actually the same person in both roles, they are both such distinct personalities. That’s why it’s interesting that you think Jane Danger’s character seems more like Jena’s character, Spills, from The Yo-Yo Gang. Jane is playing a girl who is a lot more street-wise than Georgie, so she’s a lot tougher, and Jane was so good at playing her. I don’t really try very hard to make the characters seem realistic so that just proves what good actresses they both are. Maybe if Jena’s character Georgie stays on the street, she’ll end up being just like the girl Spills that Jena played in The Yo-Yo Gang.

MRR: You mentioned that there may be an official release of the film soundtrack of The Lollipop Generation. Has there been any further discussion about that project? And can you say a word or two about the music you included, and what function you believe music should play in cinema?

Yes, a soundtrack is going to be released because all the songs are so great. I asked the musicians that are in the movie to write a song for it and the only thing they had to do was to include the word “lollipop” in the song, or title, or both. I wasn’t in touch with some of the people since we’d done the scenes so long ago, but the people I was still in touch with all gave me great songs they all wrote specifically for the movie. Because there aren’t only actors in the movie, but actors and singers and musicians and artists and writers and filmmakers, it’s not like a Hollywood movie where everything is compartmentalized, where each person involved is assigned only one task. With the movies we’re making, everyone can try different things, so that some people did acting and cinematography, and some did acting and the lights, and some did acting and writing songs. With our movies, it’s like all the different scenes come together, the music scene, the acting scene, the art scene and the movie scene and it makes it more exciting. And everyone who is in the movie and wrote a song comes from a different city—your project, Anonymous Boy and the Abominations, are from New York City, the Hidden Cameras are from Toronto, Jane Danger is from Chicago, The Swishin’ Duds, Gary Fembot’s band, is from San Francisco. So it’s not just music and art and acting scenes coming together, it’s scenes from all different places in North America. And then there’s also Mariae Nascenti, from Milan, Italy, which makes it intercontinental.

MRR: It seems to me that some of the organizations that are allegedly supposed to be there to help the runaway and throwaway youth who become ensnared in prostitution and teen-porn, are often revealed to be exploiting the youth as well. One such scandal involved a place called Covenant House that was right on the corner of the street I live on. The regularity of these scandals might be one reason why teens choose not to put their trust is such institutions, but I wonder if one message of your movie is that such teenagers can learn to put their trust in each other and in themselves? And if that is the message, do you think that is enough of a solution?

There’s no doubt that such scandals seem to occur with regularity in a variety of institutions. It would only make sense that young people feel they can’t trust such institutions, but what I hope is that this recognition begins to go even farther. Religious institutions have been seen to betray the trust of young people but government agencies are also accountable. In fact, the government itself should be accountable for the circumstances of the lives of the young people who are regarded as “throwaway kids.” In so many ways, on so many levels, the fact that kids have to grow up on the street is a testament to how government, police, religious, economic, and educational institutions, in almost every country, don’t really work and certainly don’t have the best interests of their younger citizens at heart. It’s time to realize that all these institutions, the very countries we live in, have abandoned the younger members of their societies, have let them be exploited, have not protected their rights, have put them in jails, or mental institutions, invented new “disorders” so they can drug them up, or let them live on the streets, and as such, are not deserving of any respect, or sense of loyalty or patriotism. Young people have to put their trust only in themselves and, if possible, each other. There’s no other choice. Is that enough of a solution? No. But pragmatically, right now there aren’t a lot of options. I think young people have to trust themselves and each other. And if they can help each other survive, then the next step will be to try to educate themselves so they can find a way to tell other about their lives and the truth can get out.

MRR: I was thrilled that one of the scenes I shot for you made it into the movie, but I also wonder why the second scene we shot didn’t make it in. Is it typical that some of the scenes you shoot do not make it into the finished films, and what are some other examples of scenes that were shot for the movie that didn’t make it to the final cut?

I don’t remember the other scene we shot, Tony! Maybe it didn’t turn out, because I don’t remember ever seeing it and I don’t have it on any of my outtake reels. You never really know if a roll will turn out or not. When we were rushing to get the film done in time for the Images Festival, I had filmed some scenes with Jena for the credits, and Scott Berry had filmed some scenes of me and Andrew, and we sent the film off express post so we could get it back as soon as possible. As soon as it arrived, Scott phoned me up and I rushed over to watch it. We were really excited to see it so we set up the projector right there in the office, turned off the lights, and turned the play button on and…nothing. There was nothing on the film at all! That’s the thing about Super 8, you never know what you’ll get. Sometimes a roll will come back and everything is tinted blue and it will look beautiful. Other times they’ll be some big flash of light like an explosion, and other times suddenly in the middle of a scene everything will go red. It’s very exciting because you never know what will happen. Some people think these kinds of things are mistakes, but I love them. I put all the mistakes that ever happened right into The Lollipop Generation.

MRR: You recently uncovered a can of footage that was shot for the movie and you’ve since edited this footage into the final film. I am curious to know if you remembered the lost footage while you were editing the film for the Images Festival. Were you fretting and wondering where it was…or had you simply completely forgotten about it until you re-discovered it? And I’d also like to know how and where this footage was found, by the way.

When I was editing the film, I did keep wondering if there was footage that I was forgetting, but I’d looked through almost twenty rolls of extra footage and hadn’t found anything, so I assumed that the shots I thought I remembered filming must not have come out when they returned from the lab. This was besides the three half-hour reels that constituted the original edit of the film, all done using the Super 8 viewer and splicer. When I went back to do a re-edit, I decided to look through every single roll one more time. It took me about a week to look at everything but I finally found all this footage that I hadn’t seen in years. It wasn’t all on one reel however; it was on various reels that I’d labeled as outtakes. All in all, it was about three minutes worth of footage and it was really exciting to be able to use it for the re-edit and incorporate it into the film. So, since the last time you saw the movie at the premiere, there are new scenes I filmed in the summer, plus the lost footage, and lots of new voice-overs that Jena and Andrew did that are so funny and great. It’s the new and improved Lollipop Generation!

MRR: The character that Vaginal Davis portrays is in some ways both funny and frightening. What was your reasoning behind this disturbing and seemingly unhinged character in the film?

No one could have played that character except Vaginal Davis. She is, of course, a true comic genius. But because of her comedic talent, it’s easy to overlook the fact that in the thirteen minutes she’s in the film she’ll teach you everything you could learn in a seven-course, three-semester year at university. People pay thousands of dollars to learn what she can reveal to you in one film. She’s covering so much ground in this performance; it’s astounding. People don’t really notice all this because she’s just so funny, and they’re laughing too hard to pick up on everything she’s doing. People have commented, and it’s true, that Vaginal is so far ahead of her time. We filmed this more than ten years ago and yet all of Vaginal’s dialogue, which she conceived and improvised on the spot, is totally contemporary and totally relevant to everything that’s happening today. As an actress she’s absolutely fearless, and it’s so amazing to watch. That’s why she can embody two seemingly contradictory impulses and be both funny and frightening at the same time and make it all work. With the film, I wanted to create something that could be both funny and frightening all at once. I mean, the film is presented as a kind of children’s story, very like a movie made for younger people, almost like a fairy tale; it’s the story of a girl who runs away from home, only to enter a kind of bizarre world filled with monsters that she must contend with if she ever wants to find her way back. Except in my film, the monsters are pedophiles, and pornographers, and playground perverts. Just like in real life!

MRR: I fear I offended one of the actors Andrew Cecil when I innocently (I swear) compared the explicit scene in the movie to porn. Were you similarly offended?

It’s a tricky question, because of course the word pornography means so many different things to so many different people. Certainly The Lollipop Generation isn’t pornography by today’s standards. But it would have been fifty years ago, just like Jack Smith’s movies and Warhol’s early movies and Kenneth Anger’s movies were considered pornographic, or even twenty years ago, like Nick Zedd’s movies were considered pornographic. For that reason, I wouldn’t say I was “against” pornography, since I’m sure you can still find plenty of people who would think all the underground movies from the 1960s right up ’til today, including The Lollipop Generation, are pornography. But I’m not “for” the pornography industry. They’re just putting out another product, adding to the endless dross that fills up this consumer society we have the misfortune to live in, and like all big industries they don’t care about their consumers or their employees. They only care about making money. I’m not “for” any industry like that. So, in that sense, The Lollipop Generation is the exact opposite of pornography. And Andrew is working with me, starring in my movies, doing the voice-overs and helping with the sound recording and lots of other stuff, and we’re trying to create an alternative to that, so it becomes very important to make it clear that we’re doing something really different. So even if people are nude in the movie and having sex onscreen, they’re doing it for very different reasons, with totally different ideas behind it and with very different goals, and that’s what we want people to know. People were shocked by that scene with Andrew and Paul and Scott and Mark, but that’s good because then they begin to see what it is we’re doing differently and why we’re doing it.

MRR: When do you envision yourself beginning work on a new movie, and can you say a little bit about what you would like such a potential new movie to be? Is there anything you feel you would like to express through the medium of filmmaking that you haven’t done yet?

I think a lot of people liked The Yo-Yo Gang, and they thought this new movie would be just like it, but it’s very different. I don’t want to make the same movie over and over and it would be impossible to do that, anyway. So, I think a lot of people were surprised by The Lollipop Generation; it wasn’t what they were expecting at all. And the next movie will be different too, so, if people think it will be the same as The Lollipop Generation then they’re going to surprised all over again! I’m just figuring out what the new movie should be based on what people are saying about this one. Someone wrote that I just point the camera at my friends and let them do whatever they want and, actually, I didn’t really do that, but I think that’s a great idea and next time I will do that. And people have written that there isn’t much of a story, so for the next movie I want to have even less of a story. Anything that people think is bad about my movies is what I aim for. They’re just going to keep getting worse and worse and worse. Or better and better and better, depending on your point of view. For The Lollipop Generation, I put in every shot that was a mistake. If the color changed in the middle of the scene, I put it in. If there was a big flare-up on the film because of a light leak, I put that in. If there were weird white lines on the videotape, I put it in. I love all the mistakes. All the things that people think are mistakes are good. That’s my message.