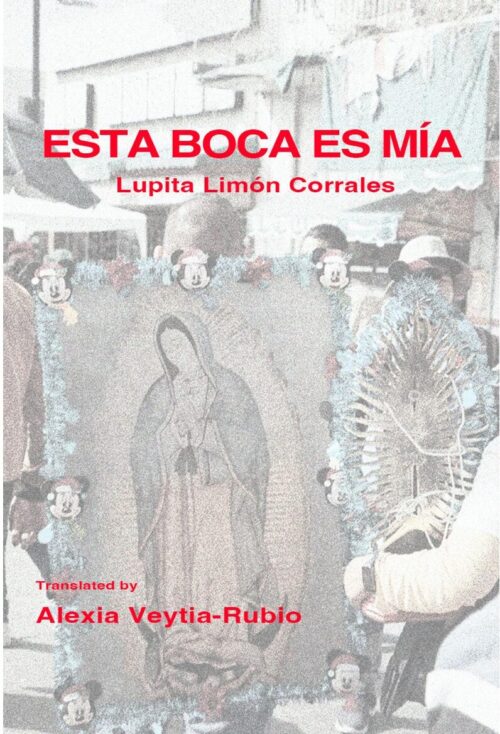

ESTA BOCA ES MĺA Lupita Limón Corrales, translated by Alexia Veytia-Rubio

ESTA BOCA ES MĺA is a bilingual book of poems that are pointed toward faith in solidarity. Corrales’s poems tell stories about tenant struggle, misogyny, and acts of anti-imperialism—also about karaoke, romance, and comradeship. The book is illustrated with photographs from the neighborhoods in Los Angeles where the poems take place. Within many of these poems are snapshots of tenant nerve: A mother moves into a party supply store. A widow shakes her husband’s ashes along the doorway of their house that’s been put up for sale. Someone picks church roses and is admonished to hell by a neighbor—before a nun interjects that “The roses belong to everyone…” (Heaven’s Green Lawns)

Corrales works with LATU (Los Angeles Tenants Union), an organization that organizes tenants to fight evictions and build tenant associations. Tenant associations are formed around a building, a common landlord, or a neighborhood to organize strategically against harassment, neglected habitability issues, evictions, and displacement. Lupita is focused on language access across the organization.

These poems are wise to the long arc of hostility on inhospitable lands. “In this war against living, I take my position on the side of eternity” (Divinity’s Guests). Una Boca mentions many people whose strength rings through Corrales’s work: Leila Khaled, Emma Goldman, Daisy Zamora, Saint Teresa, and Saint Vibiana. The locus of these poems reach from Los Angeles to Gaza to Mexico, invoking the lineages of saints, poets, and anarchists engaged in class struggle against those who control “Bulldozers and fences [that] terrorize the poor”—and those “against children…olive trees…bakeries, libraries and poetry.”

Her poems are romantic and spiritually salient, though grounded in material conditions: “Every time a laundromat closes / the property value goes up…” Her work addresses the imbalance between the prioritization of real estate and the quality of our lives. Her voice speaks with strength from a life-instinct within the tenant struggle, in line with her judgments: “…Even in hell the jasmine still blooms / and the sun shines on each of us / whether we deserve it or not” (Old Linens).

The title ESTA BOCA ES MĺA refers to an incident where the author was banned from karaoke at a bowling alley. Alexia Veytia-Rubio translates: “I’m a conduit just like a mic. This mouth is mine/and it never stops screaming.” The night out is in celebration of solidarity: drinking palomas, a widower singing to his deceased wife, a friend smashing a glass in support when she is kicked out of the bar.

Corrales writes about working with the Mohawk Street Tenants Association in Echo Park, which successfully organized to legally ban “Renovictions.” Renovictions are a method of gentrification in which landlords displace their long-term tenants to remodel their properties and hike up rents. Corrales’s poem QUERUBIN/MOHAWK STREET is about helping Memo (a Mohawk Street tenant) fight an eviction after he is laid off from his job in a cherub factory that he had worked for decades. The poem contains both factory cherubs and angelic encounters. His daughter Lulu learns strategies for door-knocking at church and uses this skill to bring tenants together, sharing information about their housing situations with each other. Lulu asks a neighbor: “A quien le tendremos miedo, / si hay solo un juez?” Questions of materiality, privatization, and displacement become divine, angelic, and existential. The poem ends: “We pray to love the angels more / than we fear the devil. Then / we see the angels everywhere.”

Strategizing against a common class enemy can breed resentment. Navigating the city’s bureaucracy—burnout, breeding malaise rent-free, like bitter fruit flies in the head. Yet these poems reignite our quicksilver and are not disheartened by the work.