Create to Destroy!

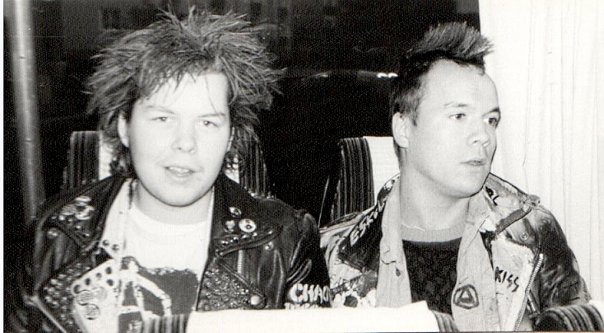

Stuart Schrader

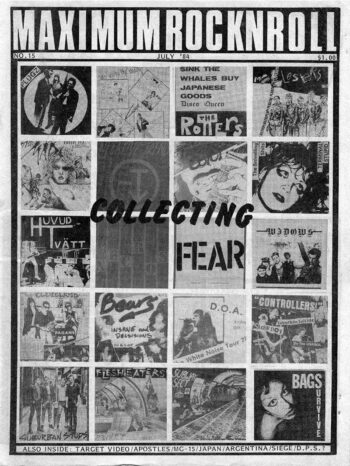

You may have heard the name Stuart Schrader before, as he did Game of the Arseholes zine. This was a highly respected zine in the “rawer” punk scene which you may have inferred from the title which references ANTI-CIMEX. He has done countless interviews, some of which have appeared in MRR such as MISSBRUKARNA and MELLAKKA. Oh, and don’t forget the ANTI-CIMEX archive! I am hoping for a re-issue of his zine, but for now here is an interview (by Amelia ANOK4U2):

How’d you discover punk?

First, thanks for the interview. I appreciate the Create to Destroy! feature because I think it is really important to recognize the blood, sweat, tears, and labor put into the punk scene that goes beyond just playing in bands. It would be incredible if we rewrote punk history not from the perspective of bands only but from a more holistic perspective of everyone who contributes, including those whose idea of “do it yourself” is to do nothing but just be a punk!

Anyway, I came to punk in a way that is almost unimaginable today: with great difficulty. I knew about punk years before I had ever heard it. I learned of the band names MINOR THREAT, BLACK FLAG, and DEAD KENNEDYS through mentions of them by guy named Glen Plake, who was an extreme skier with a giant mohawk who was semi-famous in the early 1990s. But it was before the internet and because I didn’t know any punks, I didn’t really know how to find the music. I discovered a DEAD KENNEDYS badge in a suburban CD shop, but they didn’t, as far as I could tell, have any of their CDs or cassettes. I was a pretty disaffected, angry, and lonely kid, and I was listening to mainstream metal and grunge at the time. Eventually, I met some punks, including one with whom I’m still friends: Nick Turner, who played guitar in COLD SWEAT and WALLS. He made some mixtapes for me, and it all began. Nowadays, one can use a search engine to discover so much, but it’s hard to imagine YouTube or downloaded mp3s being as precious to anyone today as those first mixtapes made by Nick and other friends were to me.

Yeah it used to be difficult to get into punk, I miss the hunt. Do you like ANTI-CIMEX?

I would say that I am obsessed with about three years of ANTI-CIMEX’s history. On most days, I think their second 7″ is the finest hardcore record ever produced: just uncontrolled, sheer rage. I am also quite fond of their third 7″, as well as compilation and other tracks recorded circa 1983 and sung in Swedish. I do like their later output, but my life would not be diminished if I never heard it again. The 1983—1984 stuff, though, is essential.

On the Anti-Cimex Archive, I have collected a lot of information and ephemera about ANTI-CIMEX and SKITSLICKERS. I have tried to make the postings interesting and compendious, but it is difficult to be totally accurate, especially because there are lots of competing stories to be found and because I don’t speak Swedish. There is another cool blog in a similar spirit by a Swedish dude that fans should check called Victims of a Bombraid. Members of ANTI-CIMEX are on Facebook, and more ephemera is appearing online. Still, I am proud that I have put a lot of unique material online for free and easy access, stuff that is nearly impossible to find elsewhere. My favorite posts are one with complete info on the eight SKITSLICKERS sleeve variations and one on a few pre-CIMEX bands. I do have a lot more material that I would like to put online someday. It’s a slow process.

You’ve written a lot. Where have you been published?

I’ve written about music mostly in my own fanzines, first Disturbing the Peace, then Game of the Arseholes, and now Shit-Fi, which is only online. I’ve written liner notes and promo materials, too, for my own and friends’ releases. In addition, I’ve contributed columns, articles, interviews, book reviews, and even letters to the editor for MRR. I wrote an extended review of Lipstick Traces by Greil Marcus for The Brooklyn Rail, a monthly broadsheet, a few years ago, which expounds some of the ideas I’m constantly developing and refining on Shit-Fi. These days I’m writing less about music than I used to (though I published a few new things on Shit-Fi this summer, two reviews, of Blast and Fiendens Musik, and one other article on how punk dealt with one manifestation of the extreme Right in the late 1970s/early 1980s).

I recently finished a doctorate in American Studies at New York University, where I wrote a dissertation about the effects of counterinsurgency practices, training, and technologies deployed overseas during the Cold War on the policing of American streets. In short, the book is an analysis of the centrality of policing to US empire and the centrality of US empire to policing. I’m now revising that dissertation into a book. I’ve been writing a lot on this and related topics, some for academic audiences and some for more popular audiences, including in Jacobin.

What’s your connection to MRR?

I started reading MRR in the mid-1990s, when Tim Yohannan was still alive. In the summer of 2000, I was living in Santa Cruz briefly, and WHAT HAPPENS NEXT? played there. I remember talking to Robert Collins and asking if it would be possible for me to visit the MRR house, and he assured me, in his friendly way, that no random kid like me would ever be allowed into the house. Haha. Soon after that I trekked to San Francisco for the KUSF record swap, which was near the MRR compound and full of MRR types, but it wasn’t for a few more years until I visited. I first wrote for MRR in 2001 when a coordinator asked me to contribute scumpit articles. It was an honor. Over the years, a few close friends have been coordinators, and I am really proud to watch the great work they’ve done. And, of course, I’m proud to have contributed

This is actually the third interview with MRR has done with me. The first was part of a roundtable that a few buddies and I contributed concerning music-focused fanzines (as opposed to more lifestyle, political, or personal fanzines) and another was in 2009 about Shit-Fi. One thing I would say is that some writers write something and then move on and that’s it. For me, writing about music, I feel like I am constantly revising, rethinking, renovating, and elaborating a corpus of ideas, so the latest thing I write about ANTI-CIMEX is strongly connected to things I wrote about the band 15 or more years ago.

How many issues of Game of the Arseholes were there?

Game of the Arseholes had an idiosyncratic numbering system. It went 1, 2, 3, 4, 4.5, 4.6, 5, 6, 7, 7.5. So that is a total of ten issues. Sam of Crazy Spirit/Dripper World and I have talked about reprinting either the whole run or selections as a new fanzine, perhaps accompanied by a cassette. It could happen.

That would be amazing- I really hope the Game of the Arseholes series gets reissued. What was your formatting like?

Basic. It was a combination of utilitarian word-processing output for text and simple cut-and-paste. Nothing too exciting but I like to think it was a pure expression of the form.

Where did you print your copies? Did you have friends at Kinkos? Postal scams?

Issues 1 through 5, though not 4.5 or 4.6, were all offset printed by my friend Josh, a punk and professional printer who was running Upstart Productions, a streetpunk label and distro at the time. The others were photocopied. As far as scams go, I follow the CIRCLE JERKS: deny everything.

How extensive was your distribution? What were the trades like?

I tried to distribute the zine for free as much as I could. I would send bulk copies to distributors like Havoc or Vacuum or whatever and ask them to send out one issue with each order they received. As the zine grew in size, it became more difficult to send them out for free, but I tried. When I ran my own record distro, I sent copies with orders. And, yeah, I traded too. Overall, copies circulated widely, across the globe. A few issues were part of something called the Fanzine Underground Committee on Knowledge (FUCK), which Dave Hyde and I created. It was basically a way to distribute a group of fanzines by a group of friends (or frenemies) all together in one. Some fanzines included were created more or less exclusively for the FUCK Packet, and others, like mine, were distributed outside the Packets. I thought these were really cool, and they included some of the best fanzines of the early 2000s. Ultimately, though, Shit-Fi reaches many more people than a printed fanzine could.

Are you still in touch with punks you traded with and people who read Game of the Arseholes?

To some degree, yes. I met so many of my friends because of the zine and record/tape trading, but our friendships then have extended far beyond that initial connection. Now, every so often when I travel to other cities I’ll meet people whom I knew only from fanzine or distro orders, which is really cool. And many people who read GOTA read Shit-Fi now.

What was the “Disclose era” like? Do you feel like that time for a certain type of noisy punk is dead and gone?

Well, I’m the first to admit that I was not an instant fan of DISCLOSE. I had heard them and owned some of the records in the late 90s, but the sound didn’t really click for me until I heard the track on the “Iron Columns” compilation, released in 1999. From then on, I was hooked. So I’m grateful to Jack Control for having included DISCLOSE on that comp. For a few years from 2001 to 2005 or so, nothing seemed more exciting than the Japanese crust scene, with FRAMTID, DISCLOSE, DEFECTOR, EFFIGY, etc., putting out amazing records. I am really happy that I was able to be a part of it, exposing folks to the music through my zine, putting out some records myself, and helping get Crust War Records and Overthrow Records in people’s hands outside Japan for reasonable prices.

The crazy thing about the “Disclose Era”, as you call it, is that the band is way more popular now than while it was around. Even the US tour was less of an event than I think it would be now. Today, DISCLOSE patches and shirts are ubiquitous. Even 10 years ago, I think a lot of punks thought of the band as a joke. So today might be the real DISCLOSE era. Of course Kawakami’s unexpected death increased their legendary status, but all of us who knew him would give all of that back to have him still alive. I’ve written extensively about Kawakami after his death, both in his obituary published in MRR and in liner notes in the recent reissue of the “Yesterday’s Fairytale, Tomorrow’s Nightmare” LP, released by La Vida Es Un Mus. As for today’s noisy punk: it does almost nothing for me. It strikes me as stale, but that’s just me.

What times do you feel the most nostalgic about in punk in your lifetime?

The worst times: I feel nostalgic for the late 1990s, when there was a low-intensity war on the streets of New York City between various factions of skinheads and/or skinheads and punks. Going to shows was often terrifying. It was awful, but it was also when I was introduced to punk and to New York City’s streets, after growing up in the suburbs. Because the battles were on some level about politics, even if in an incredibly stupid way, it seemed like punk meant something. People’s lives were being endangered by right-wing violence (shortly before my time, punks had been killed, and skinheads you’d see at shows were engaging in gaybashing afterward). To fight back physically, something I never personally had the courage or wherewithal to do—though I aligned myself with RASH and occasionally played the role of scout to warn people of lurking dangers—seemed so important. At the same time, those years were the end of a long era that extended far beyond subcultural battles in New York City. Little did we know that all sides of the political battle would lose. The Lower East Side was effectively destroyed by massive gentrification, quality-of-life policing, etc. It’s unrecognizable today (with the exception of ABC No Rio’s continued existence). I’ve written about these feelings a bit here.

I also feel nostalgic for the period that came after. If the mid-1990s in NYC were marked by the explosion of streetpunk, the early 2000s were marked by the almost complete disappearance of DIY hc punk in New York. Those of us who put on shows had a really hard time finding spaces and ensuring that people would attend. There were a few bands (INSURRECTION, SANGRE DE LOS PUERCOS, FALSE SECURITY, etc.). They weren’t even necessarily very good, but they were OUR bands and OUR friends. Relatively big touring bands would barely garner fifty heads at a gig. Now, the tiniest show in NYC for an obscure but bad band will have hundreds of punks show up. The punk scene in NYC is huge now, with amazing stuff happening. But I miss when it sucked. Haha. There was some ineffable quality that is now gone, now that the bands are good, there are cool and stable show spaces, etc. So I guess I’m nostalgic for basically the mid-90s to the mid-2000s, the first decade of my punk life, but two very different scenes.

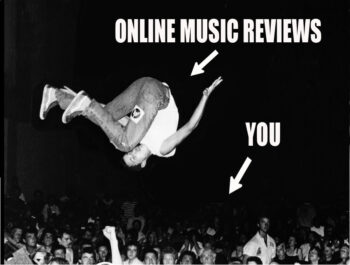

It’s amazing what the scene is like now in NYC compared to what it was like then. And I came up in that scene that “sucked” but I thought it was pure magic and still do. How do you feel that the internet has changed punk?

In good ways and bad ways, of course. But even though I’m terribly impatient I miss the old ways, when it wasn’t so easy to find artifacts and information. The chase really is better than the catch, and the internet has made the chase too easy.

I second that. Tell us about the Shit-Fi website.

I talked a good deal about my thinking behind the site here. Basically, the idea behind the site was to give really in-depth coverage to music that seemed on the surface utterly unworthy of such coverage. I wanted to highlight the bad, the worse, and the worst (and some very obscure stuff that fell through the cracks because it never quite fit with trends). It’s since grown to encompass a lot more than simply the most primitive, lo-fi, and ugly music out there, but in a sense that is at the core of the project. Still, times have changed even in the short period since I started the site (it went live in January 2007). Now, I would argue that lo-fi music is among the most popular forms of pop music. Listen to a lot of current hip-hop (like BOBBY SHMURDA): it’s super simple, super primitive, unadorned, almost live-to-tape, etc. Similarly, a lot of rock is now unconsciously or semi-consciously replicating very simple 80s/90s indie music in the penumbra of punk. So due to the massive democratization of recording technology, it’s clear that the hierarchies that structured the possibility and necessity for punk and shit-fi variants of punk and other forms of underground music no longer exist. It’s all scrambled. Does the underground as such even exist anymore? Arguably, it doesn’t. So I guess the project today is about evaluating these contexts and their shifts over time. In total, I’ve published almost 60 articles of varying length (some several thousand words long) on the site, with another dozen or so contributed by others, not including the Anti-Cimex Archive.

How do you feel about message board culture?

To stop reading message boards, after spending a lot of time on them for many years, was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.

Why are you political?

Well, we all are, some more conscious of it than others. But I think you’re asking about why I write about politics in my music writing, from an explicitly left-wing perspective. In a sense, I don’t know how not to; this is how I approach every aspect of my life, by trying to carefully consider and perhaps shape the politics of it all. My music writing, since I was an adolescent, has unintentionally chronicled my political shifts. I recently stumbled across an early issue of Disturbing the Peace, my fanzine from high school. In it, I referred to myself as a liberal. Ha! I guess because it was the Clinton years, the word was an epithet, so I wanted to adopt it. For about ten years after I turned 18, I would’ve referred to myself as an anarchist or ultraleftist. Now I’m less certain what to call myself. I’m not an ultraleftist but I’m on the far left, though unaffiliated. Anyway, everything I write is a political intervention—obviously a small one. I think it is important to see music itself and writing itself both, in different ways, as inherently political. The best thing to do is to be reflexive about what our political contexts and choices are in any given situation.

Do you think punk is still political?

Of course. Even the choice to avoid or ignore politics in punk lyrics is political. I think that today, if you look at MRR, which of course is not fully representative, punk is realizing a lot of its possibilities that seemed out of reach years ago in terms of being more inclusive and less reactionary. Many of the primary voices in punk in the United States today are women, queer folks, people of color, recent immigrants. This is a different politics from the politics of punk in the 1980s, though. Bands like Conflict saw punk as, or wanted punk to be, an adjunct to a broader antiwar, anti-nuclear, etc., movement, which was in some ways on its heels then. An argument could be made that the rise of punk was a kind of symbol of the impending exhaustion and defeat of the left in the US and the UK. In contrast, I think it would be a stretch to say that punk is an adjunct to the emergent social movements today like Black Lives Matter or Occupy Wall Street of a few years ago. At the same time, some punks are participants in the movements (and the anarcho-punk lineage of the global justice movement, the antecedent to OWS, deserves recognition). Today, nevertheless, the lessons of these movements are enacted increasingly within punk. Exchanges are a bit more fluid, and even people’s self-identification as punk or politically radical or whatever might be more fluid today than it used to be. The acceleration of all of that is enabled by digital technologies. But it is also a symptom of neoliberalization, insofar as neoliberalism entails the heightened entrepreneurial fabrication of self as market commodity and the destruction of democratic political structures. Although participation in a collectively organized movement remains a possibility, the reality is that sustained collective political organization is almost entirely absent from US social life. Occasional and attenuated participation then becomes a notch in the head-board of the entrepreneurialized self. “Been there, done that” is the credo of neoliberalism’s reaction formation against the collective, and the occasionally extreme lifestyle choices of punk fit in perfectly. Overall, we’re more likely to Instagram our bad haircuts than our participation in left-oriented political organizing on #flashbackfriday, but the two can function similarly.