Politics and Punk in Hawaii: Steve Hart talks with Keli’i Beyer

I first met Keli’i Beyer when my band flew to Oahu for a weekend of shows. He welcomed me, along with his roommates, into his home. I was struck by his intellect and passion towards Hawai’i. We spent a couple afternoons arguing and passionately debating ideas and we’ve become friends since then. When I was reminded that I should contribute some things to MRR’s website, I thought of Keli’i, and this is the conversation that took place over a few days.

—Steve Hart

MRR: I know that you have been involved in a lot of different groups — especially working with domestic violence. How did you get involved with that and when did you start?

Keli’i: I’ve been a domestic violence educator now for about six years, working with the Domestic Violence Action Center here in Honolulu. My job is to talk with intermediate, high school, and sometimes college, students about the aspects of violent relationships, and how to help friends/family stay safe or get out of these dangerous situations. Initially, through my work with various community activism (i.e., anti-war protests, environmental issues, human rights campaigns, Cultural Native Hawaiian activism, promotion of gay/LGBT rights, as well as the issue of pro-choice and women’s reproductive rights), I was introduced to the appropriate networks and landed a job as an educator in the DV field (domestic violence). I try to use my experiences working with community organizations and activism as a way to connect the various issues of oppression evident here in Hawaii, and connect the dots about why these issues occur in the first place. This includes, but is not limited to, the overt militarism and history of land stewardship in Hawaii; having an economy that relies solely on tourism and the military (and how that keeps us reliant on the US for resources, food and energy, rather than a “homegrown,” sustainable and uniquely cultural approach); the sense of heightened nationalism post-9/11 (and how this influences our attitude towards American interaction with the rest of the world), and importantly, understanding how the collective cultures here in Hawaii can affect our relationships with one another, especially around ideas of race, gender, and overall identity…

MRR: Did you go to school (college) in order to do this?

Keli’i: I was actually raised in Chicago, and moved to Hawaii in 1998 to attend the University of Hawaii (and because this is the only place i ever wanted to live, even growing up). I always knew that I’d like to study art in college, but really had no idea what I would do with it. Since both my parents are teachers, I always kinda figured I’d end up doing something similar, though really had no idea until I graduated from UH in 2005 and got my job at the Domestic Violence Action Center (at which point I had already been working as an art educator with the Honolulu Academy of Arts, so that was putting my art education background to use). I think being educated in a creative field such as art has given me the mentality that it’s more important to gain awareness and experience through life, than to seek making a quick buck at the expense of those around me (including my friends and family, the larger community, and globally, through limiting the detrimental impact I might have on the planet).

MRR: How has being kanaka (Native Hawaiian) affected you growing up here and what advice would you give young kids who are kanaka and have a hard time struggling with identity?

Keli’i: I am a part Hawaiian, and have always identified more with my Hawaiian heritage growing up (since my dad was a proud Hawaiian, and my mom died when I was a little kid, therefore cutting off most ties to that side of my family). Living on the mainland and feeling really connected to the island culture is hard, as there’s not only a physical disconnect living way in the Midwest, but there’s also a major cultural disconnect as well. It’s really difficult being a kid who’s interested in Hawaiian cultural identity, being surrounded by a society that simply views Hawaii as that “magical tourist destination,” where all Hawaiians live in grass huts on the beach, husk coconuts for a living, and surf and do hula all day long (even more annoying when I hear that from tourists coming here for the first time, expecting all locals to cater to their beck and command). It was important to have this identity, but also discomforting to move to Hawaii and realize how little I actually knew about my heritage. As well, it was kinda sad to see how kids here in the islands take for granted what a truly special and unique culture they have here. I was also really surprised how little the majority of “locals” actually knew about their host culture, the Kanaka Maoli. If anything, there seems to be this idea that if you live in Hawaii, then you’re a Hawaiian. Whenever I hear that type of mentality, it always makes me cringe, for it’s almost like saying a whole group of people that lived here for centuries matter very little in the larger scheme of things (even though, ironically, these indigenous “Hawaiians” got to these islands through a series of Polynesian and Micronesian migrations over a couple thousand years).

It’s definitely helped me understand more about my role as an activist and educator, to see what struggles face our people, and where the majority of these troubles are coming from. But it’s dually important that I can educate others about the history of the Hawaiian Islands, and how that history continues to affect us today (through economics, religious disparity, loss of culture and the struggle to regain access to the past; drugs/alcohol/crime/poverty/homelessness, land issues, and a whole slew of other issues). Any advice I have for fellow Hawaiians is to understand more about where we came from, so we can begin the healing process, move forward and grow from the mistakes and lessons the past has taught us. I absolutely love the fact that spoken Hawaiian language has seen a resurgence, and I would definitely advocate that more Kanaka Maoli take part in learning and teaching their language, as well as the other aspects of Hawaiian culture that will help us move ahead.

For me, a lot of this has come from taking part biannually in a religious ceremony called makahiki, which I attend on the island of Kaho’olawe. For those that don’t know, this is a small island that was used by the US military as a bombing range for over 60 years. In ancient times, this island was seen as the center of the Hawaiian island chain, and was the most important place for young Hawaiians to learn about navigation and the celestial “map” they used to guide their travels throughout the Pacific. To see an island as culturally significant as Kaho’olawe relegated to target practice by an institution like the US military is a constant source of pain for me (and many other Hawaiians), and I utilize this pain as a source of inspiration to maintain diligence in my pursuit to teach others about our struggle, and as a source of hope for the future. To continue the healing process that has begun on Kaho’olawe and elsewhere throughout Hawaii, there is much work still to be done.

MRR: It’s important to me that people hear the truth from the kanaka and it’s very rare that this is told in punk rock circles. A follow up question, do you think that it’s hard to be kanaka and be involved in punk rock? Do you get shit from the other side of that? Do you see a connection between the Hawaiian sovereignty movement and punk rock anarcho-type politics?

Keli’i: Is it hard to be kanaka and a punk rocker? Well, in some ways yes, and in other ways no. In many ways I am forced to separate those two sides of myself, as the punk rock world (small as it is here in the islands) and the world of being a Hawaiian rarely seem to intersect. There are many differences, whether it’s appearance or musical preference, that forces a divide between these two communities I associate with, sometimes making it difficult to find full acceptance in either.

For example, most Hawaiians I know that represent being a Kanaka Maoli (i.e., by taking part in cultural ceremonies, speaking the language, dancing hula, etc.) listen to island music, slack key guitar or Hawaiiana, and roots reggae. They will take one look at me, with my non-tribal, punk tattoos and plethora of piercings, and think I must be some kind of freak, because that’s not what Hawaiians tend to look like. Granted, there are many Hawaiians who sport piercings and tattoos (especially given the historical significance of tattoo throughout the Pacific), but most Kanaka Maoli would associate punk music as being too “mainland” or “haole” (lit. meaning “without breath,” but used as a term to imply Caucasian). Hawaiians involved in the punk scene are a rare sight. And though there are some of us, I can’t think of any band that sings in Hawaiian and plays punk rock. I could be wrong, since I’ve only been living here since 1998 (and there was a pretty thriving ’80s Hawaii punk scene). And, as far as most of my punk friends go, I can’t think of many that would be interested in attending Native Hawaiian ceremonies (other than devouring the delicious Hawaiian food; which, for many people, is all it takes to celebrate being Hawaiian!)

As well, there are certain restrictions to living a punk rock lifestyle to its fullest potential here in Hawaii, which could be why it’s not something found much amongst NÄ Kanaka. Given the high cost of living and the ideal of Hawaii being a tourist destination (i.e., sweep the streets clean of any unsightliness, especially uppity youth and vagrants), makes it really difficult to associate as a punk, per the squatter/anarcho lifestyle. Kids on the continent and globally are able to achieve this more easily, with access to squats, anarcho community centers, and a much better organized network of venues that can connect the various punk rock communities together. In Hawaii, there are very few venues, the cost of land makes it utterly impossible to find a long lasting house or factory to squat, we’re an island chain (adding further restrictions to travel), and basically, the idea of “punk” seems very unnatural to most people here, who look at the punk community with the same light as drug users and criminals. Even with the punks here, very few of them associate with anarchist politics, let alone work towards creating that type of community here.

Culturally, there are also values that conflict heavily with those of punk rock. Local kids from Hawaii tend be raised under very Confucianist tones (with the large influx of Asians to work the plantations for the wealthy haole land owners) and a heavily isolated and largely religious worldview. The history of missionary influence on these islands, coupled with the nationalistic fervor that is so commonplace (due to the attack on Pearl Harbor and the concurrent militarism), has created the perfect situation for complacency and acquiescence. Unlike my upbringing in Chicago, where I was encouraged to ask questions and think freely; in Hawaii, we’re taught to suppress our desire to question, speak out against authority, and stand out from the crowd; all values that punk rock strongly defends. This makes for glaring limitations to someone like me, who is dually defined by punk rock values and those of a Native Hawaiian.

As far as whether I see a connection between the Hawaiian sovereignty movement and anarchism, unfortunately, my answer is a resounding no. And this exists for a variety of reasons. First off, I don’t think that many Hawaiians understand what anarchism truly is, associating it as chaos and destruction, rather than a viable system for liberty, justice and equality for all. This is understandable, given that the history of politics here was tarnished over 100-years-plus with the illegal overthrow of Queen Liliu’okalani, which transformed their monarchal society of island fiefdoms into a consumerist, military-run territory (in the interest of profit gain for corrupt businessmen). And though a change is essential for the political climate of Hawaii, especially with our reliance on the military and tourism to sustain ourselves, I can’t see Hawaii returning to an antiquated political structure based on a monarchial rule of bloodlines and royal ascension.

In many ways, the system of politics that some Hawaiian sovereignty activists claim to desire is based on feudal values of tributes and serfdom, royal powers, and classes of citizenry. This existed in Hawaii long before Western contact, beginning with the arrival of Tahitians in Hawaii around 1000 AD. Their mighty armies overthrew the indigenous people inhabiting these shores and set up a hierarchical system, complete with gods, rulers, workers, and slaves. Their kapu system necessitated a distinction between man and woman, and initiated a very regimented society. With chiefs fighting other chiefs for land and power, this would eventually equate into stature and historical significance. The fact that some modern day Hawaiians can trace back their lineage many generations is amazing, and something to be valued and recognized. But I don’t think that we should claim that one Hawaiian is more deserving of power than another, just because he/she happens to have royal ancestry.

To the benefit of the Kanaka Maoli, however, there are certain communal aspects within the Hawaiian culture that have existed long before the Kapu system was set up by the Tahitians. I have read texts saying that the original Hawaiians to these islands (known as the People of Mu, who likely voyaged from the Marquesas islands sometime around 200 AD), were a classless society that lived a sustainable existence with the Aina (land). They worked as communities and lived together, without the need for war or conquering each other, and lived in harmony with the world around them. To me, this forgotten society stands as a much better representation of anarchist values and beliefs than the proffered political structure of the sovereignty movement.

MRR: Do you see a way that punk rockers can get involved and support the Hawaiian independence movement? Is there a way that people from all over the world can get involved? Is there a role that punk rock can play?

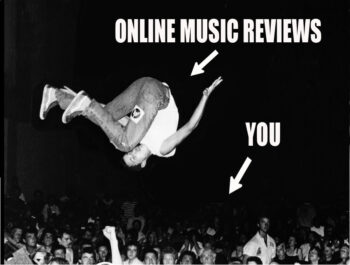

Keli’i: I think for the worlds of punk rock and Hawaiian Independence to intersect in a beneficial way, there needs to be a serious debate about the politics behind both. Punk rock, in many ways, tends to lack a political stance here in Hawaii, with a scene too PC to truly confront the issues affecting us. Overall, I’d have to say the majority of bands playing punk rock in Hawaii today tend to shy away from discussing politics at their shows or in their lyrics, preferring to dumb down the music in favor of making fans and having fun. And yet, lack of substance or not, we can’t place all the responsibility on the bands, who are working hard enough just to keep the scene functioning as a working unit. The punks that go to shows are just as guilty of using the “scene” as a means to simply find fun, get drunk and mosh, while rarely considering the historical potential of punk rock for political mobilization. But it’s understandable that most scenesters lack a political edge, given our extreme isolation, the absence of a heavy touring scene (which could expose more punks to radical politics) and especially the fact that they’re surrounded by a world that denigrates free thought, asking questions and rocking the boat. And who wants to be Buzz Killington at a show and talk about the atrocities our government is guilty of here and abroad; or how about how our military is intent on sending off our friends to fight and die in wars that never end; or better yet, addressing the inconsistencies with the ways the Kanaka Maoli are treated in their own homeland (plagued with poverty, crime, high rates of drug use, alcoholism, domestic violence, diabetes and heart diseases, suicide, teen pregnancy, etc.)? With the realities of surviving the high cost of living in Hawaii during a recessed economy, who doesn’t want to hit the bars on the weekend, listen to some good music, and try to forget about their struggles?

And, truthfully, the only organization that remotely discusses radical, leftist (but not anarchist) politics in Hawaii is the RCP, which tends to be a little too hardline for many of the punk scene kids. Perhaps there is the need for an intro to politics and being politicized before our scene can move towards action or momentum in making real change. Most of the punks I know here that do touch on politics tend to come at it more from a reformist, need-to-get-out-and-vote, Obama-is-the-man kind of perspective. In my opinions, this is all just malarkey; electoral politics are mostly a band-aid solution set up to keep the power in the hands of a select few, who also happen to be those wealthy enough to convince the general masses to buy their bullshit at the ballot box

If kids in the Hawaii punk scene are to get more involved in making real changes, with the hope of utilizing their uppity, youthful energy and bring about positive, social change; I think more punks need to pull their heads out of their asses and take a good look at the world around them.

That being said, there are many ways already that punk rock ethics are involved in making social change here in Honolulu. Shows and concerts are thrown frequently where the funds raised go to an important issue, such as the recent tragedy in Japan after the March 2011 earthquake. Very often, these events call upon a dedicated group of individuals to donate their time and energy to a cause bigger than themselves, for an issue that is pertinent to their lives. Another way that punks have been able to raise community awareness in Honolulu is through the vibrant bike scene, complete with infrequent Critical Mass rides and other events to show solidarity for the two-wheeled folk. And while the bike scene tends to wax and wane in popularity (largely dependent on the trendiness and cool-factor amongst the scenester kids, rather than its viability as an alternate mode of transportation); it’s still an important step into getting more punks politicized. At the very least, by promoting biking, there’s the hope that our community can gain a better understanding of class issues, as well as address the detriments of Hawaii’s reliance on big oil (number one in the nation) and a lack of options.

Another venue where politics have trickled in is with the Chinatown art scene, which hosts a monthly First Friday event in the streets, bringing out the masses for a night of drunkenness and decadence. And though most attendees to this monthly soiree would not associate themselves with the punk rock scene (which, by any means, is still the minority scene throughout the islands); and there’s an overwhelming sense that most people attend the event to be “seen” (as though this is LA and they’re on the red carpet); there is still a resurgence of politics to the world of art in general. Some pieces I’ve seen here have addressed subjects such as human and civil rights, environmental problems, gender inequality, and raising cultural awareness. Granted, most of the art is pretty abstract and apolitical, but it begins with baby steps, and getting more people to think outside of the box is always a positive step. There’s also been a resurfacing of graffiti artists in the islands over the past few years, which has sought to legitimize graffiti as a viable form of artistic expression. And while this subversive art form is typically more aligned with the hip-hop scene (which can be just as guilty as punk of placing ego before substance); we must support every venue that promotes a revolutionary stance, regardless of whether it’s punk rock or another scene. These are all positive steps, and I’d like to see them surface more regularly in the punk scene.

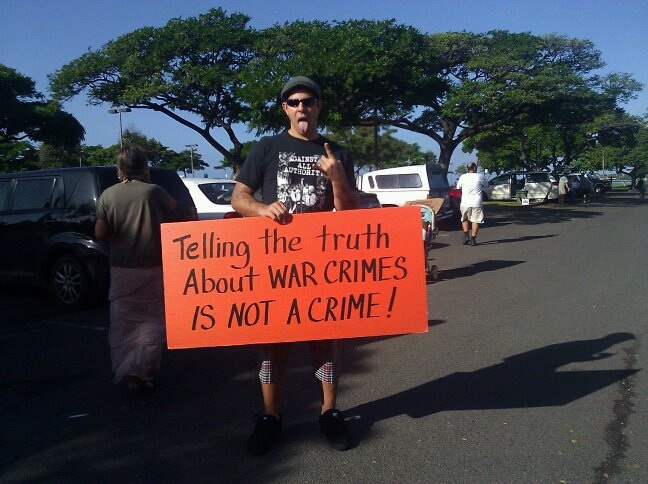

It’s my hope that the scene’ can return to the days of punk shows being available to all ages (as too often the majority of shows occur at bars, where the music is secondary to getting drunk with friends). How are the kids supposed to learn about punk rock and the ethics involved (i.e., DIY, free thought, abhorrence to authority, etc) and build a stronger community, if there’s never a venue for them to join together? Social networking and access to online resources can only go so far when you’re an estranged teen full of angst with no outlet to express your rage and frustration at the world. We need a revival of political involvement within the scene, complete with zines and groups organizing the punk rockers to become active in speaking out in protest. There was a day when Food Not Bombs, Refuse and Resist, and the Radical Cheerleaders were regular faces at the shows. Encouraging the dissemination of radical thought used to be a regular aspect of going to shows. It was a common thing to see the same kids from a punk show the night before waking up early to attend an anti-war rally the next morning at 8 a.m. (still hanging or drunk from the nighttime debauchery), ready to give the world a middle finger salute. I believe that before the punk scene in Hawaii can begin working with the Hawaiian community towards Independence and reciprocity, there needs to be a major redefining of our priorities and the goals behind our music. In my opinion, what is the point of making punk music collectively as a scene, when there’s no momentum behind it as a community?

Globally, I believe there is much that can be done to support the Hawaiian movement and the Kanaka Maoli as a whole. It begins with recognizing the historical wrongs that have been perpetrated against a race of people, and how that history continues to live on today through economic, cultural, spiritual and political disparities against the indigenous citizens of Hawaii Nei (lit. “Greater Hawaii”). It begins with learning the truth behind what a select group of American businessmen did in 1893, illegally overthrowing a sovereign queen, and implanting a false government with the purport of acquiring rights to resources (i.e., sugar cane, water rights, and land for the US military to test their weapons and host their war games). It begins with becoming akamai (lit. “smart,” “educated”) about the role we have as visitors to the Hawaiian islands, and what ways we can begin to give back to the land, the people, and the culture. It means viewing the indigenous peoples as equals and recognizing their sovereign right to define themselves and the way their lands should be used (whether communally or privately). It begins with tourists visiting our islands making their first stop the lo’i patch (hydroponic garden where taro is grown), and working with the people to heal the land of the past couple centuries of abuse. Education is key; and until we dispel the false belief that Hawaii is a paradise to be enjoyed by all (which it can be, but not at our current rate of consumption and unfettered growth), then we’ll continue to destroy this place that so many love and cherish.

It’s my hope that one day I can play music and participate in a scene that uses its potential to make positive changes for the world. We must start small and make meaningful choices so that future generations can follow in our footsteps, and continue the changes we have initiated. More concerned citizens looking out for each other in sustainable and real ways (rather than the rugged individualism expressed through American ideology) will bring about such an important sense of solidarity as a community. And then, we can begin to heal the damage that has been done against this island nation and its people.

I’d like to take a second to validate and showcase some of the positive elements I do see in the Hawaii punk scene. From year to year, I’m continually amazed at how the much the punk scene has changed, from new bands playing on the scene (after most of last year’s bands have already called it quits); new venues hosting shows (like the once-a-month punk show at the Waikiki Sandbox); newly dedicated groups of individuals working together to keep the scene alive (e.g., the No Suck Fest crew for getting Honolulu more interested in DIY punk rock); or old hands dishing out their own time and money to host and promote shows (like Jason Miller and Hawaiian Express). In a city largely averse to punk music and the culture it propagates, the finely tuned intricacies of maintaining this scene too often falls on the shoulders of those behind the scenes, out of the limelight and recognition, who do it out of love for punk rock and not for fame or fortune. This also includes those punks actively searching out venues to host shows; those that bring bands to the islands (usually at a disadvantage to their wallets, especially with the high cost of travel, reimbursements, promotion, etc.); those that rent and operate practice spaces to support a host of bands; and many other ways that fellow Hawaii punks give back to their scene. These actions, while not overtly political, are integral in maintaining a healthy and functioning punk rock scene, and should be highlighted for their importance and necessity.

And while my previous views expressed a certain contention towards the lack of politicization within the current incarnation of punk rock Hawaii, there have definitely been individuals and bands that maintain a strong connection to the issues in Hawaii Nei. There’s bands like White Rose from Maui, who combines political ideology with the old school sounds of hardcore punk to make a powerful addition to the Hawaii punk scene. Others, like the 86 List and Black Square (shameless self-promotion), led by Josh 86 of Unity Crayons fame and now the Downbeat Diner (a thriving late-night café where starving punks and Chinatown scenesters can grab a bite to eat), continue to discuss a variety of issues; from the War on Terrorism, to gay rights and other civil rights abuses. And though these two bands may have traded in a bit of their former political aggressiveness for a more “unity-based perspective” (critical, while maintaining a positive, upbeat and hopeful outlook); it’s important that I can participate in a band which poses an alternative viewpoint to the mainstream ideals. An additional band (who no longer plays, but which supplied the scene with a few years of social consciousness and teenage angst) was the ska band Golfcart Rebellion, whose Less Than Jake-influenced sound allowed the all-ages scene to dance and shout, while lending voice to a variety of issues. I find it especially important that punks can make political and socially-conscious music, with the hope that their words and actions will inspire future generations of disenfranchised youth to become active themselves.

Another venue that I personally have sought to promote a degree of awareness to the issues (especially a place where I attempt to expose the masses to a wider variety of punk rock music) is through my weekly radio show called The Radical Noise Addiction. This radio show, hosted through the college station KTUH (one of the last remaining all student-run radio stations in the country) has given me the weekly opportunity to play punk and hardcore music on the radio in Hawaii since 2001. The fact that this show occurs from 12 to 3 a.m. every Sunday night (during safe harbor hours, which means I can play swear words without having to edit the songs) is extremely important to me, as it allows listeners to hear punk rock in its rawest and truest form, without sugar-coating or diluting its true content. Much of the punk music I play articulates a level of political thought rarely heard on the radio these days (and especially not on the top-40 dominated, Clear Channel-owned commercial stations). It also gives me the opportunity to discuss revolutionary actions that have occurred globally, such as the recent successes and failures of worldwide riots and protests; government corruption and other inequalities; as well as upcoming events here in Hawaii. The fact that we have a major banking conference occurring here in November 2011 (the ever-contentious APEC) is definitely an event that deserves publicity, with the hope of rousting Hawaii’s youth to become aware and motivated to protest. In this way, I attempt to link up the Hawaii punk scene with a more radical perspective on the world, while giving the punks a source of inspiration to become active locally.

Truthfully, it’s not easy being outspoken about politics here in Hawaii, and even less so in a scene that’s as separated from politics as our punk scene tends to be. It’s disheartening to be involved in a social movement for change when those around you are so wrapped up in the eternally superficial and overtly narcissistic tendencies of self-promotion. These trendy hipsters seem to care more about their clothes, hairstyle and shoes than anything relevant to making positive changes to their world (and they’re also the ones that others look to for validation of their own egotistical endeavors). It’s sad to think how difficult it is to be politicized and get others encouraged to mobilize, and then finding yourself confronted with a wall of close-mindedness and outright ignorance. If anything, this alone is a just cause for confronting the apolitical habits of Hawaii’s punk scene.

Ironically, the place where I see issues such as Hawaiian sovereignty and cultural rights showing face is not amongst the punk rock crowd; but rather, within the roots reggae scene (which, historically, tends to focus more on idolizing Bob Marley, smoking weed, and sporting the red/yellow/green reggae logo, than educating the masses towards political and social action and change). However, on the rare occasions when I am pulled away from the punk scene in favor of some local flavor, I have been pleasantly surprised to see an element of awareness scattered amongst the usual proclamations of smoking weed, praising Jah, and preaching the word of Rastafarianism. This includes a handful of individuals actively working towards healing the Aina, replanting the forests with indigenous species (and fighting the spread of invasive, non-native plant and animals species), propagating the ‘Ålelo Hawai’i (lit. “speaking Hawaiian”) through cultural charter schools, rebuilding the ancient fishponds and heiau (Hawaiian temples), and more. I’d have to say, from personal experience, most of the folks I know involved with the clean up of Kaho’olawe would never be caught dead at a punk show. But, throw some roots reggae beats into the mix, and these kids are ready to rage. Now, we just need to find a way to bring these two very contrasting genres of music together to maximize our capabilities for making change in Hawaii.

As far as my involvement in the scene, I continue to play with local ska band Black Square, of which I have been an active member since 2004. We are currently working on the release of our fourth official album, most likely to be self-titled, which is set to hit the streets mid-June. It is, in my opinion, our most dynamic album yet, and a release that we’re all very proud about. I will be joining my Black Square brethren for our first cross-country tour this summer, as we embark on two weeks of the Vans Warped Tour. Our portion of the concert series will take Black Square from Orlando, FL,through the Midwest and Rockies, before ending on the West Coast in Portland, OR. This will be our eighth official mainland tour, and I hope it will be our most successful one yet. We can be found on Facebook, or check out our web page at www.blacksquareband.com.

[Editor’s note: Lots of videos from Black Square are available on YouTube but if you watch only one, let it be this one.]