Looking back at Tim Yohannan, 20 years later

We still can’t believe that it has been twenty whole years since our founder Tim Yohannan left us for good. We miss him dearly. His work, both in Maximum Rocknroll and elsewhere, has permanently altered the world of punk, and has affected millions of people worldwide. Instead of writing an essay about his work or creating another eulogy about him, we asked people to send in some of their memories of Tim Yohannan. Here are some of our favorites…

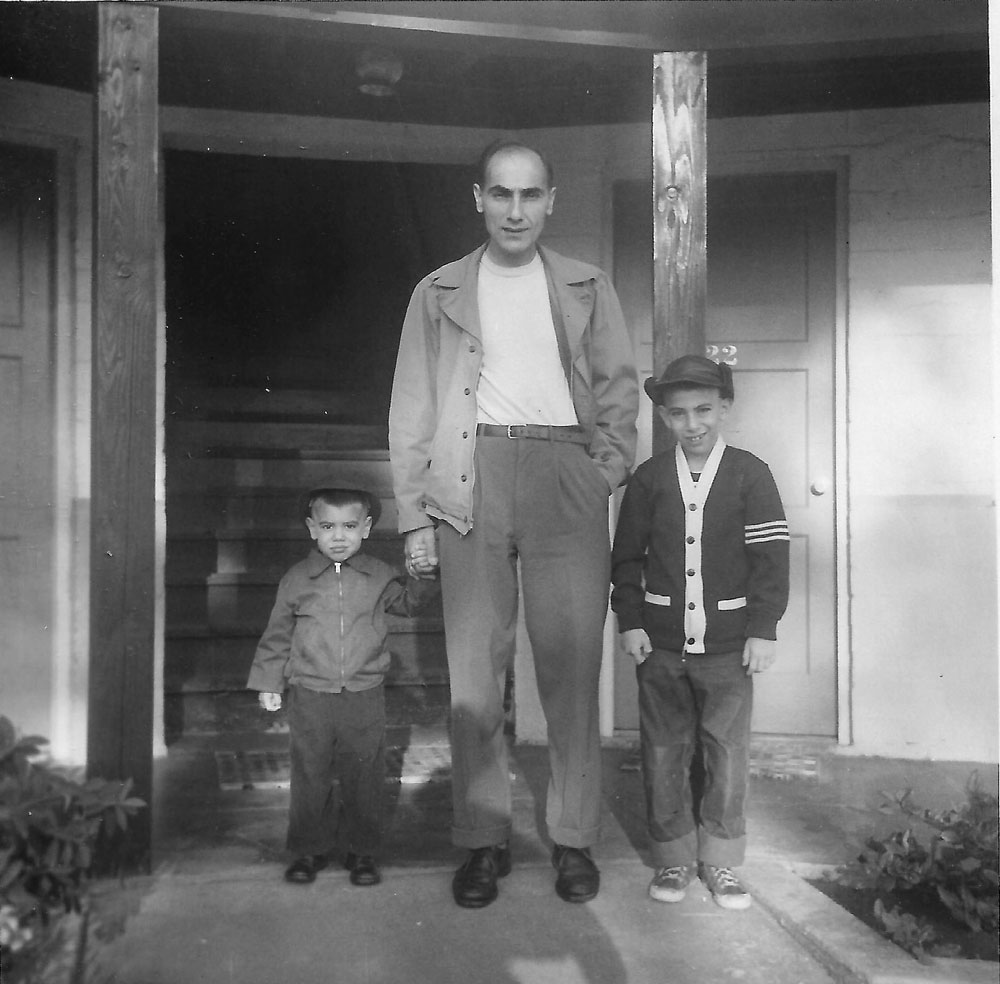

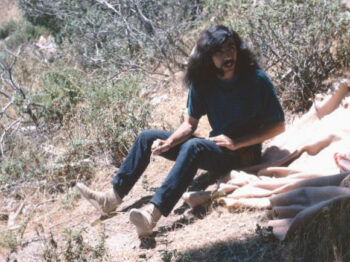

We are thankful of Tom Yohannan, Tim’s brother, for providing these pictures of Tim during his youth, as he was developing into the figure that he became known for. We hope this provides a more complete glimpse into the life of Tim Yohannan than what you may have known in the past.

I started reading Maximum Rocknroll in the late ’80s and moved to SF in the summer of ’95. By August I was at MRR doing new issue day and zine reviews. Tim had already announced he had cancer, and jobs he had monopolized were being spread out among shitworkers. I took the opportunity to grab a mail day and edit the letters section. As a reader, I liked Tim’s strident and straightforward approach. I felt a strong responsibility to try to match Tim’s hard line and not let bullshit slip by.

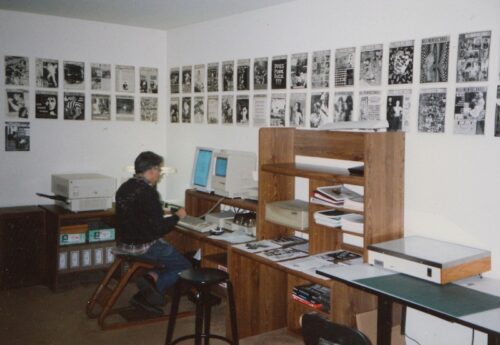

It was Tim who showed me how to use a mouse and a Mac. I found him an effective but not patient teacher. I happened to be there when Tim signed his will, and said, “Lemme get my camera.” I knew Tim hated being photographed, and would especially object here. But Tim’s style was to playfully fuck with you, and I didn’t mind giving it back. Of course he got pissed and said, “Don’t fucking dare,” so I didn’t.

Like most, especially newer, shitworkers, I deferred to Tim. The slogan was “whoever does the work gets to decide,” and Tim, even with fewer duties, did by far the most. But for sure he was a forceful personality. Once, pre-email, a columnist was traveling and submitted their work hand-written. Tim said, “Who’s gonna type this?” in a way that sounded to me like, “No one’s gonna type this.” I thought it would be easy and worthwhile, but I wasn’t gonna contradict him, and the column never ran. At new issue day, he argued with/yelled at a guy for being friends with a local band who’d recently signed with a major. The way he talked to him, I assumed Tim had known the guy a while, but he was new like me. The way I remember it, after venting, Tim softened and said he wasn’t attacking the guy personally. Like Tim, I’m from the East Coast/Northeast US, so I thought it was a reasonable way to act. From reading the magazine, I didn’t expect much different.

In my experience, if Tim thought something wasn’t right, he’d lean on you about it, quite directly. But also he was serious that probably he wasn’t gonna be there much longer, and other folks would have to use their own judgment to run the magazine. I was part of a group that fucked up a new issue day task. Tim was in a state, and tried to fire me from doing the mail in the aftermath. I told him I wasn’t fucking up the mail like I helped fuck up new issue day, and he relented.

As part of doing the mail, I would enter record label or band addresses into the database. Some folks wouldn’t put their address on the letter or the record, which was a bigger issue back then than it is now. I didn’t give a fuck if there was no contact info, as I saw it as the band’s or label’s responsibility to make it available if they wanted to hear from people. What I didn’t fully appreciate was how different Tim’s attitude was from mine, giving his record collecting obsession. He would hunt down any clue he could find. He asked me how come this one band has no address. I said it wasn’t on the record or the letter. He said, “What about the return address on the package?” I told him, “That shit’s in the recycling.” He said I should get the address there if it wasn’t another spot. I said, “Next time I will.” He was like, “What about this one?” I said, “You know where the recycling is.” He gave me a look, stormed out there, and came back in the with cardboard mailer. He shook it at me and yelled, “It’s the mail person’s job to do this!!!” I said, definitely, from now on, that’s what I’ll do. I call this story, “The Time I Told Off Tim Yo.” It’s the only time it happened. Another time, I did some stupid shit regarding the letters column and got called out on it. Tim just said, regarding my initial fuck-up, “I wouldn’t have done it that way,” and let me handle fixing it how I saw best.

I only ever saw him put on two records, the Jam LP and the Rolling Stones, England’s Newest Hitmakers. I told him I got the J Church Nostalgia For Nothing double LP singles comp for six bucks. He didn’t seem impressed and offered drily, “Must be your lucky day.” Once, the subject of old hippies came up, and Martin Sprouse asked him when was the last time he spilled the bong water. “Probably twenty years ago to the day.” The thing about his laugh was true. I read Tim as being tense, and thought it powered his hearty laugh.

Years later, while I was still a reviewer, an ex-shitworker asked me how I felt about Tim Yo being a Stalinist. I’d had a while to think about it. At first, I’d gone through disbelief and denial. It was MRR that had a lot to do with me thinking society is bullshit, and I regard Stalinism as actually worse than the current American system. Working with Tim, I never got the impression he was down with that shit. Eventually, I came around to acceptance. Tim’s life’s work of herding a bunch of (mainly) anti-authoritarian radicals didn’t leave much space for state communism, thankfully. In hindsight, it seems to me that nobody thought Stalinism was cool from reading MRR, while other (more righteous) political tendencies were amplified. I do remember a time when the editor of another, supposedly “punk” magazine was in town and called up to see if they could stop by and visit. Tim had read in the magazine the editor saying they wanted MRR to stop publishing and asked about it. The editor allowed they did feel that way, so Tim said, “Hell no, you can’t come here.” I was there when Tim was asked, about this or some similar topic, “Is this Risk (Tim’s favorite board game, in which armies fight to conquer the world) or real life?” Tim made a face like, “Is there really a difference?”

—Jeff Mason

The last time I saw Tim he made me sign his “do not resuscitate” order as a witness. I laid out the scene reports or the letters, fighting hard to get fucking PageMaker to behave more like Quark Xpress, while Tim and his crew of old commie pals played Risk on a handmade board in the living space of the MRR house. I was young, beyond socially awkward, and always in awe/intimidated by Tim.

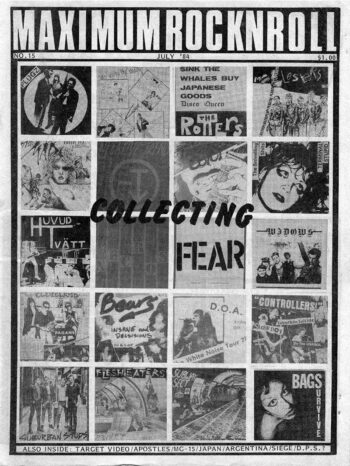

Every time I walked in the house, I was like “I am actually at MRR, working on MRR. I have a key to the MRR house.” I was a dumb weirdo from oppressive, pre-Internet, ’80s, Republican, suburban Michigan, for whom discovering MRR (#57!) was like the…the most liberating thing that had ever happened to them. Like, holy shit, I don’t have to live here and try to act like these people and be miserable? I can be myself and fight for what I believe in and do stuff to make things better? And there’s an entire soundtrack to this movement and it’s fucking incredible? It’s obvious, but it was a revelation to 13-year-old me.

And the fact that I was actually living in California, going to punk shows every week, and working at actual fucking Maximum Rocknroll…it was sort of unbelievable. I’d hear people talk shit about Tim at Gilman and be like, “But…but…he’s Tim” It was like they didn’t get it. Sure he was a pain in the ass. Sure he was didactic. But his single-minded force of will gave the world MRR and Gilman and everything those two institutions gave to the world. It’s easy to sit in California and complain—legitimately—about problems these institutions have, but you have no idea how much MRR and Tim saved lives of weirdos and outcast and marginalized kids all over the planet. To me that’s his legacy. And that record collection… People say you should never meet your heroes, but actually, Tim was both super cool and exactly what I expected him to be. Crazy cackling laugh, eager to talk about baseball (I remember talking to him a lot about the interview he did with Scott Radzinsky from Scared Straight and Steel Pole Bathtub, and how bummed he was that Scott only wanted to talk about punk rock, and not his day job of pitching in the MLB) and capital-P Punk rock (I was like, “Oh, you’re rehabilitating Ben Weasel” after the Lookout Crucifixion cover and he died laughing, because we both knew the Stalinist reference to his editorial management style was accurate).

Anyway, to finish my story, that night I witnessed the DNR order, I finished my layout and paste-up and tried to slip out the door without bothering anyone. Tim stopped me. He was like, “Don’t leave without saying goodbye. You need to say goodbye.” I was like, “Oh, yeah, bye Tim.” And that was it. Within a few years, a kid and jobs meant I drifted away from active involvement in the scene. My fanzine editing tastes turned from dumb punk zines to dumb video game zines (and now skate zines). My music tastes calcified—I probably own fewer than ten records recorded this century. It happens. I still buy every issue of MRR, though, and I still am incredibly thankful to Tim and the crew he established for saving me from a life of misery and showing me what could be done with your life. The punk world has no end of problems and bullshit but Tim kicked it into gear in a way that still pays benefits to weirdo kids—and adults—all over the planet. I think about him all the time and I miss him a lot.

—Chris Snak Fud

In the early/mid ’90s I was living in San Francisco and dating an MRR columnist. One night we were out and she needed to grab something she’d left at MRR HQ so we went over and went in (she had keys). It was kind of late at night, so we tried to be quiet, but a bleary-eyed Tim came staggering out of his room and took one look at us and called her over. He was sort of whispering, but I could clearly hear him ask her, “What’s going on and who is that thug you brought into my place?!?” I was always proud of being described as a thug by Tim Yo!

—Anthony Begnal

I grew up in DC in the ’80s. I bought my first issue of MRR at the campus record store at the University of Maryland College Park, I think it was issue 9, with the Stalin on the Cover. I have been a subscriber pretty much ever since. I grew to admire Tim’s steadfast position on a lot of issues, especially relating to commercialism and the introduction of right wing political views into hardcore. While I did not agree with many of Tim’s political views outside of hardcore, I did agree with most of his positions about the hardcore scene. I often wish Tim was still around to inject some venom into the discussion, or lack thereof, of these issues today. In the summer of 1987, I sublet my room in a DC area punk house, threw some belongings into a backpack, and hit the road. I wound up in the Bay Area and of course went to the newly opened Gilman Street Project to check it out. Back then, you had to buy a membership card, and it was Tim who sold me my card and explained the rules to me. I saw a lot of bands there that summer, like MDC, Fang, Christ on Parade, and I was at the infamous Feederz show where they threw dead animals into the audience. I’m pretty sure it was Tim who barred me and a crew of vigilantes from coming back into the show and storming the stage. In retrospect, we would have been playing into the Feederz’ game, but I was pretty outraged at the time and still think whole stunt was in very poor taste. Tim wrote to me a few times, once or twice about records for review, once to ask about an interview for Code 13, and once to ask me if I wanted to do a regular column. Since I had grown up reading MRR, I was thrilled at the opportunity, and I’ve been on board ever since. As noted above, I really wish Tim was still around to hold people’s feet to the fire and speak with authority about the current state of the hardcore scene.

—Felix Havoc