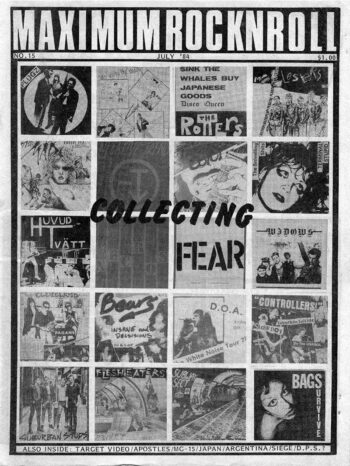

MRR archives: Maximum Rocknroll #5 “¢ Mar—Apr 1983

Hiya, punx! This one took a little extra time to get posted but I hope it’s worth the wait. Continuing with the MRR Archives Series in celebration of our 30th Anniversary, Maximum Rocknroll issue #5 features some totally classic shit, like interviews with Social Unrest, Bastards, DRI, FU’s, Die Kreuzen, No Labels, Subhumans (UK), our first scene reports from Holland, Brazilian and NE Ohio, and a MDC European tour diary…. Not only that, but we have a very special intro for this issue…

Ruth Schwartz was one of the first people I met at Maximum. I remember, as a nervous 13-year-old guest DJ on the MRR Radio show at KPFA in Berkeley, how I was treated not like little kid but as a comrade, of sorts, by Tim and Ruth. An early introduction to the Ways of Punk that I would come to know and try to uphold myself. Although I never got to know Ruth very well, she has always been someone I hold in great esteem. Her resume includes being the original “co-owner” of Maximum Rocknroll, owner of Mordam Records, the person who spearheaded Blacklist Mailorder, and now the operator of High Performance Advocates and author of The Key to the Golden Handcuffs, a book about business which features a chapter on MRR’s Tim Yohannan.

During our conversation I was taken aback to learn how little involvement Ruth actually had in starting Maximum Rocknroll magazine. (And by “little” I mean none!) But I was equally stoked to learn more about her pre-Maximum days as a college radio DJ, and about MRR’s early crusades against the thuggery of skinheads and the local rock music establishment.

—Paul

How did you get into punk, and how did you meet Tim and get involved in MRR Radio?

I grew up in Huntington Beach. I migrated to Santa Rosa, CA, for junior college when I was 17, and then the Sex Pistols played in San Francisco. That was my first punk rock show. Right after that there were punk rock bands in Santa Rosa, including the Breakouts. There was a crew of us who were like our own little music scene, like 12 of us. But I moved to San Francisco as quickly as I could.

I was doing the Harmful Emissions radio program at KUSF. I had never met Tim Yohannan. I knew of him, but I don’t think I had met him until he walked into the KUSF studio one night to meet me. He walked in and said, “Do you want to be on our radio program?” I knew the Maximum Rock & Roll show (MRR Radio). I was a broadcasting student at San Francisco State. I was a music director at that station out there. I had done some shows at KALX (UC Berkeley’s station) and I had finally finagled my way onto Harmful Emissions. Tim came in and asked me to come be on Maximum Rock n’ Roll. That’s how I met him.

Why did Tim want you on MRR Radio?

Because I did a kick-ass radio program! When I started at MRR, Rick Scott was behind the board — Tim had another partner before that, Al Ennis — and I think he was just looking for more people. He was just out going, “I need a gang.” I think at that point he had just gotten Ray Farrell to come on, a little bit before me, and he started pursuing Jeff Bale at the same time.

Tell me about Harmful Emissions…

On KUSF, the Vietnamese news was on until 9 or 10 o’clock, and then they would shut down the station. The Harmful Emissions guys would show up at 11 or so and turn on the transmitter — they got permission from the school. Nobody else came back in the station until 7 or 8 in the morning, so they’d just do it… It was awesome, and it was always amazing that the Jesuits let them get away with what they were doing. (The University of San Francisco, where KUSF was, is a Jesuit college.)

The original three Harmful Emissions people were George Epsilante, Steven Spinali, and Tim Maloney, and they were killing it, they were just slaying it. They were awesome because they were going all night — they would just fire up the transmitter and take it until they can’t see straight. Everybody was listening to them cause they were nuts. So, I met George at a party and I just begged him, “I need to be on your program.” That was around 1980.

Basically what would happen is, when the clubs would close everybody was listening to that radio show, and all the bands would go over there and be interviewed and stuff like that. It was mayhem; it was absolute mayhem. If you look at the early ’80s it was Social Unrest, Dead Kennedys… I was a Flipper-aholic. They showed up sometimes. I was like Flipper’s house historian. Later on, I remember when MDC was there, and DRI, and the Fuck-Ups…

And then it all took off when the show hit the Arbitron ratings. Arbitron is the radio equivalent of the Neilson ratings. Harmful Emissions was way underground and all of a sudden it came above ground, and that’s when people at KUSF came in. There was this bunch of guys, and they were like, “Oh, we’re really going to make something of this. We’re gonna make this into a big station. We’re going to regulate the programming,” and that’s when they destroyed it. They standardized their programming and they put in a music director and they put in a program director and they started to can it. So I would show up at night and they would give me play list, and I’m like, “I don’t think so.”

What was your role at MRR Radio and how were you involved in the creation of Maximum Rocknroll magazine?

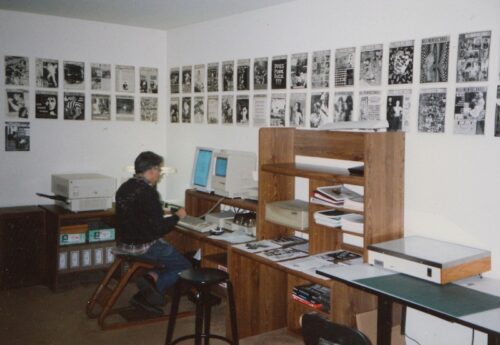

I was totally on syndicating the radio program — that was my baby. Tim gave me that because I was all about radio. So, I came to MRR Radio and I became the board-op when Rick left, and then I started syndicating it. I did it for years and years, editing it with an Xacto knife — I had reels of tape, you know — and getting tapes duplicated and sending the show to radio stations all over the world.

I don’t even remember Tim making that first magazine because I didn’t have anything to do with it. I was still in school, I was working with three radio stations, I was working with Damage magazine as well, and I don’t even remember them doing the comp. Tim and Jeff decided to do the Not So Quiet on the Western Front compilation. I literally had nothing to do with that. They put the whole comp together and they produced that first magazine to go in it because they wanted there to be all the lyrics and the band information and all that inside. It turned pretty thick. There’s 47 bands are on Not So Quiet on the Western Front, so now you’ve got at least that many pages… so that was the first issue of Maximum Rocknroll.

That’s all they intended to do, and they just left it at that for a while. I started working for Rough Trade when I graduated. I remember Not So Quiet coming out, but the only time I ever touched it was selling it at Rough Trade. And then they were like, “That was fun. Let’s do it again.”

My biggest memory of starting the magazine was they said, “Would you write record reviews?” and I said, “Yeah.” I wrote record reviews and they sent them back to me and they said, “We don’t even understand why you’re a college graduate, this writing is so terrible.” I said, “Huh… Well, would you help me?” and they said “Yes,” and I said, “Well, you’re going to have to actually edit me,” and they say “Yes.” I said, “OK,” and I kept writing, and they kept editing… and that’s how I learned to write! So I credit those two guys for that — they taught me how to write. Jeff’s a professor, they were both really decent writers, and I wasn’t.

Tim Yo bankrolled the whole thing. I mean, he had nothing else to spend his money on. The whole capitalization of MRR magazine was Tim putting up the money for Not So Quiet. That thing sold like crazy, so that bankrolled the next project. I became his business partner at that stage, for about eight years. Maximum Rock & Roll was a partnership — Tim and I partnered right after Not So Quiet came out, because all of a sudden there was money. So when he said, “Okay, we’ve got to get a bank account, and we’ve got to put this money somewhere… Would you do this with me?” I said, “Yes.” But Tim had very specific idea about how he wanted to run a business, as you know.

[Oh yes, I know! We talked more about the business side of the magazine and Mordam records, and Ruth finally divesting from MRR, but I wanted to know more about the early days — especially this…]

Can you tell me about the famous on-air debate with Bill Graham on MRR Radio?

That was sort of the beginning of the politicizing of MRR. I think it was one of the first causes that Tim and Jeff took up.

There were all these really great venues in town. Paul Rat was doing the 10th Street Hall and he was going really heavily into promoting. He’s a great guy and he treated all the bands well. Dirk was doing the Mab, and he was also doing On Broadway at that point. There were a lot great venues, a lot of indie stuff going on, and it started getting big. You could fill the 10th Street Hall every weekend… Thousands of people.

Bill Graham didn’t care about Target putting on a show, but when these big halls started filling up for a Dead Kennedys show, or when all the bands started coming up from L.A., it was a really big deal. So, BGP (Bill Graham Presents) was like, “We want a piece of that.” Somebody was putting on a show and BGP sent out thugs and basically said, “We’re gonna shut you down. We’re gonna get you on fire violation, or we’re gonna get you on something…” So Tim just…went to war. Tim went Michael Moore on Bill Graham.

Quite honestly, I think that was one of the first real political things that Tim did. He got that little pointy finger of his out and went for it. That was the first time I saw Tim go aggro. Of course, the picture is of Jeff, right, pointing the finger? But it was always Tim’s finger — he had that evil finger…

From there we went onto skinheads. We had this whole series where we were bringing the skinheads into the studio. And these were our friends. These were people we saw every week at shows, for better or worse. That was really something, I thought. Like, the Bill Graham thing was really great — that Tim was willing to muckrake on that — but the skinhead thing, you know, bringing them up to the station and… I mean, Tim kinda out-talked them.

I knew all those guys — and we were all really impassioned — but I wanted to keep a good scene. I didn’t want these guys to come in and wreck the scene. Cause they were freakin’ idiots, right? So if any of them were willing to come to the table and talk about, “What’s up with this? What are you doin’? Can we, like, stop it?”

What it did was it took those guys who were really nice guys but just kind of a little… misguided, for lack of a better term, and it kind of gave them a new perspective. It really segregated out all these little white supremacist guys. I think it had a tremendous impact because those guys that realized they didn’t want to be little white supremacist assholes, they started holding the space, basically, at these shows.

If you go back to the days of the Farm, nobody was standing up to these guys. Everybody was, like, cowering, and Tim was like, “I’m not going to cower. That’s ridiculous.” Which was good, which was really great leadership. The outcome of that was to get the guys who didn’t want to be assholes to be working toward creating a good environment for shows. I thought that was critical. I didn’t want to stop going to shows because of these guys. I couldn’t imagine a couple of guys wrecking it for hundreds and hundreds of people. So I thought it was really powerful.

I think it’s interesting that you stuck around. When you read some people’s accounts of the early punk scene, it’s like, “And then hardcore came, and the violence came and that was the end of it.” For them, punk rock was over and it doesn’t exist beyond 1981, 1982…

Yeah, but think of all the other things that happened during that time. The whole DC scene happened, then the Chicago scene popped and there was a really vibrant New York scene, Texas was on overload… there was so much good stuff going on.

Why do you think that so many people dropped out of punk at that time?

I think there was a certain amount of people who “grew up,” you know what I mean? “This is not that important to me.” And then there were people who were just what we called the weekenders — they weren’t really into it. They liked the music and they were just looking for something to do. It didn’t really speak to them. And then there were people like us. We were kinda leaders, we weren’t going to let it lie. We were going to stay there, no matter what, and go, “Here’s the really cool stuff that’s going on, that you should know about. People who are doing things right. And there’s a lot more of them than people doing it wrong.”

That whole mentality about creating an alternative and creating an alternative lifestyle and staying independent and all that, that’s a driving force. And one thing I’ve learned about my life, even now — and I’m not of these people who runs around going, “I’ll always be a punk.” But the other side is that I realize now, even in the work I’m doing now, which is completely different, I still feel like the disc jockey. I still feel like I’m going through all of this material and I just searching for the great stuff. And even though there’s all this stuff that sucks and doesn’t work, it’s like, “Yeah, but there is this other really great thing over here. So let’s use that!” I always felt that way, you know? There’s a thousand records out there but I’m going to play you the really cool ones.

PDF download of MRR #5 will be available soon in the MRR Webstore!

Read more of our MRR Archives series here.