Murray Bowles interview from MRR #321: The Photo Issue

Interview by Aaron Cometbus and Anna Brown, from MRR #321: The Photo Issue

Murray Bowles has been a ubiquitous presence at punk shows for 25 years. You will know him as the bearded and bespectacled man behind the camera in the middle of the dance floor, shooting pictures of the crowd, the band, and the scene around him by holding his camera over his head and pressing the shutter. In this unlikely manner Murray has documented the Bay Area punk scene like no one else. His pictures capture the spontaneous energy that makes punk so unique. No one is ever depicted lying in the gutter covered in her own puke—or throwing punches in the pit.

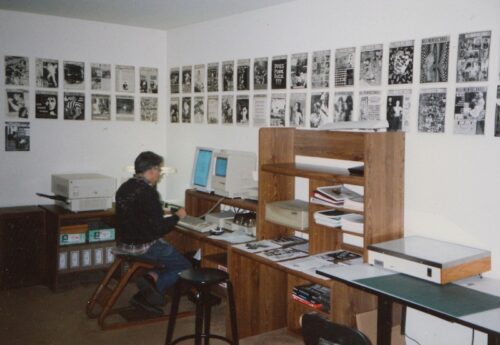

Murray is not a voyeur. Rather, as an insider, Murray is privy to the intimate moments of fun, freedom, and release: stolen glances, toothy grins, and uninhibited dance moves. When he isn’t in the pit, Murray works as a computer programmer in Silicon Valley, and plays the viola in the Peninsula Symphony and with the country punk band the Shitkickers. Aaron Cometbus and Anna Brown sat down with Murray in November 2009 over Vietnamese sandwiches and Anchor Steam.

Murray Bowles: I got started as a backpacker, taking pictures of nature. I moved to the Bay Area as a student at Berkeley from 1973 to 1976. Then I began working as a computer programmer in San Jose and some of the people who worked with me were into the punk scene. Tim Tonooka from Ripper enlisted me to write reviews for the magazine in 1982. Some other people at my job volunteered at Target Video. Tim used to take all the pictures for Ripper, but one day he asked me to do it when he couldn’t make it to a show. I had fun and I started bringing my camera to every show I went to. It was addictive.

MRR: How did you learn photography? Didn’t you have a darkroom in your kitchen for 25 years?

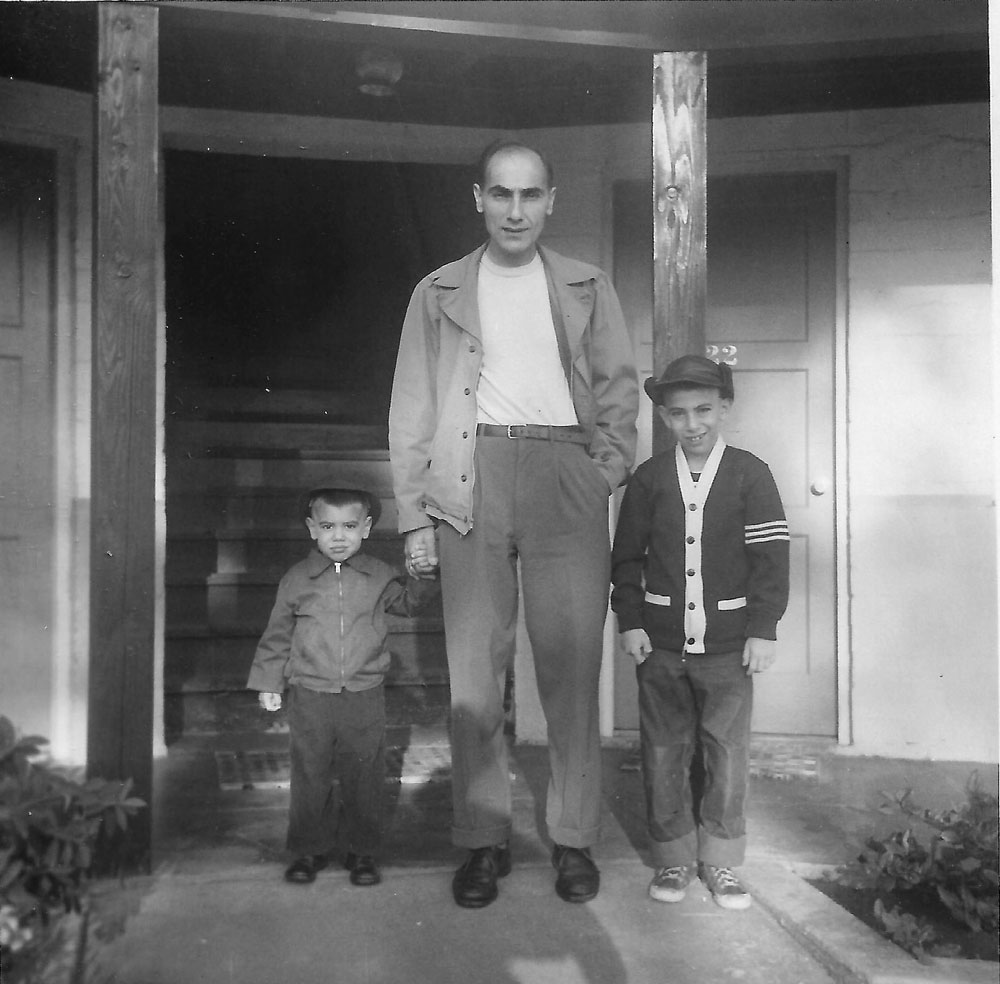

My grandfather taught me the kitchen developing technique. He used to do amazing trick photography, like making us look like midgets, peering around coffee cans.

How many cameras have been destroyed at shows?

No cameras have been destroyed, but lots of flashes. They get smashed, and the batteries tend to fall out and fly all over the place.

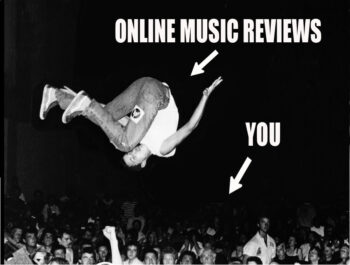

Stage divers must know to avoid hitting you by now.

I learned some things. Like never to hang the camera strap around your neck, ’cause stage divers feet get caught in it. And how to protect my face. That’s how the point and shoot method evolved—you have to avoid holding the camera up to your face.

You are always in the audience, never on the side of the stage or in the front row and so your pictures capture the audience perspective, in the middle of the action.

Yeah, I have never liked those guys who shoot metal with the ultra wide-angle lenses and a huge flash taking dozens of the same shot.

How did your style evolve? Was it a moral or aesthetic choice?

Tim Tonooka taught me to move around a lot, to go for variety. I try to get shots of everybody. Drummers are hard because if you’re in the audience lots of things get in the way. I have gotten good at shooting the singer without the microphone in their mouth.

At a certain point you switched from a manual camera with black and white film to a digital camera, in color. The pictures separate the olden times from the modern times for me. Murray BCE—before the color era.

I tried to hold off switching to digital until they made a full frame camera. I bought a digital point and shoot but they have an intolerable delay. I switched to color in 2000 when I got the point and shoot. Now I use a Nikon D300. When I started I bought the same camera as Tim Tonooka—a Canonet Rangefinder. The first shows I went to were at places like the Mab. I went with the Target Video guys to all sorts of obscure shows at strange venues. Al Flipside was very influential, too. He encouraged everyone to be more than just a witness to the scene. To do something useful. Taking pictures got me more into things. I wasn’t just a record collector that went to shows anymore.

How was it seeing your work published?

My pictures moved from Ripper to MRR. I did guest DJ spots on MRR Radio, and bands started contacting me for pictures. Tim Yohannan was often looking for something specific, and he would go through my pictures. I also started printing 4x5s and selling them for 15 cents at shows—the cost of a sheet of paper divided by four.

How did people respond? What surprised you about their reactions?

Well, it always surprises me when people want copies of crummy photos. They don’t care if it’s barely in focus if it’s of the right people. Bands always want pictures with all the members showing, but it’s really hard. It never even looks like they’re all playing. I tend to take pictures of one to two people. People bought a lot of pictures of crowd shots, depending on who was there that night.

You must have learned a lot of secrets—the secret social life of the scene.

I don’t know about that, but you do begin to notice who reacts in what way to other people in pictures. I sold multiple copies of certain people. Over time I moved off the stage and started focusing more on individual people and less on the stage. Stages are still kind of ideal, though. They are usually elevated, wide, and provide a natural view. But pictures of people playing pool in the back of the club, for example, can be as interesting as a band playing.

Whatever the subject is you always give the impression that you’re right there, involved in the action.

Yeah, well that’s the punk party line: “No boundaries between the band and the crowd.” It’s nice to be able to show that. At this punk house in San Jose last year there were shows where the whole scene was crowded into this tiny basement. Sometimes the bands were good; always the people were fun.

Your photos are on tons of albums, how did that happen? There’s the Crimpshrine record, Fang, the Minutemen, Schlong’s Tumors EP, Neurosis.

It just happened. The Raw Power album was put out by someone from LA who contacted me. I think I ran into Mike Watt at Al’s Bar when they were screening the world premiere of Desperate Teenage Love Dolls and I happened to have some pictures with me. Nowadays you just post the pictures online and send a link to the band’s MySpace page.

When your photos appeared on albums, people really started to know you and your work. How did If Life Is a Bowl of Cherries, What Am I doing in the Pit? come about?

When your photos appeared on albums, people really started to know you and your work. How did If Life Is a Bowl of Cherries, What Am I doing in the Pit? come about?

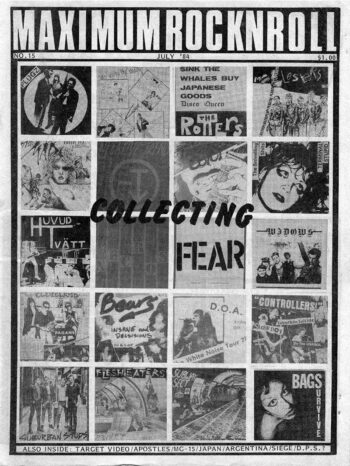

Maximum RocknRoll published my book/zine If Life Is a Bowl of Cherries, What Am I doing in the Pit? in 1987 or so. Glen Friedman was making a zine at the time and Maximum was probably influenced by that. It was Tim’s idea. We edited it together, Tim, me, and some other people. There was a certain amount of negotiation that went into the selection process

What were the criteria for inclusion?

All the shows were in the Bay Area. We tried to give equal representation to bands. Some pages were collages. I think there were 10,000 copies printed. But in MRR’s effort to economize, they used cheap paper that turned yellow. I heard they ended up scrapping a whole bunch of them.

It was a great zine though, weren’t you proud?

Yeah, I was proud.

Any more plans for books?

Yeah, there are plans.

So who are your favorite subjects to shoot? Orlando comes to mind…

Yeah, Orlando is reliable. Bob Noxious, Mark Dagger, Jello…

Who was an impossible subject?

Well, Capitol Punishment was surprisingly hard. They always came out overexposed. Agent Orange was hard, so was Naked Raygun. With some bands there is just always more action in the music than on stage. Grimple was the ideal band to take pictures of.

Your pictures are characterized by a sense of playfulness and lack of pretense. There’s something so charming about that.

Capturing people having fun is always fun. There was this real public perception of punk violence, moshing, and danger. It’s nice to show it can be both ways. It can be fun to be violent.

So what are you actually taking pictures of?

The energy and interactions. The crowd as much as the band.

So shows that lack certain things aren’t good.

Yeah, I don’t want to take pictures of people standing around, holding cigarettes in the air. There have to be good vibes, but not mindless happiness. Emo shows are unsatisfactory.

For so many reasons.

There has to be happiness and energy.

How does that mesh with your more recent subjects of arm wrestling competitions?

In a way, arm wrestling is more underground than punk.

What about other sporting events?

When the drummer of the Reckless Rebels was on his school team I took some pictures for them. Wrestling compared to punk captures some of the same intensity. Faces and motion—the physical expression of drama.

Like photographing drummers?

Kind of like that.

Talk about transitioning from photographer to musician on stage.

Well, even before I started playing with Ding Dang, two co-workers—Randy, the Target Video guy, and Rich, a record collector—and I were in the Clots. Rich and I sang. This was like 1980. Later various people heard I played viola in the symphony. So that led to collaborations with Grinch, Brian Stern, 23 More Minutes, and others. I ended up playing fiddle in Ding Dang.

How was it going from private to public? It’s nice to see background people on the stage, like Marshall going from doing sound to playing in Blatz…

I’m not prone to stage fright, but being on a stage is different than playing in an orchestra. Like, making mistakes is no big deal when you’re in a huge orchestra. But I guess it’s not in punk, either. I got used to being a spectacle—the photo guy playing fiddle. For a while I was the new guy in the Shitkickers, but now people know me as a musician, too. It’s kind of fun to play and tour and let other people take the pictures, but I still take pictures from the stage, sometimes.

You know the names of many obscure bands. San Jose in general would have been an unknown scene if not for you.

For a longtime I was an East Bay and SF “snob.” Then I started going to more South Bay shows. In any scene, good venues come and go.

You must be the only person with pictures of Los Olvidados, Living Abortions, Ribzy, Mock, and Bl’ast.

Apeface… It’s funny now, how even short-lived, long-defunct bands have a Facebook or MySpace page and new bands have 1980s hardcore bands in their top ten.

San Jose is much more suburban than San Francisco or the East Bay.

Yeah, and they have much less strict notions of what’s cool. Maybe it’s the sprawling landscape; the cliques are more spread out.

What’s the deal with 8×10 glossies? How come they are never ever good?

I think it’s that the band managers of the world don’t realize they are so uncool. No one ever looks comfortable, just badly posed.

Do you think you were able to take such amazing candid pictures because everyone knew you and was comfortable with you?

It probably helped a lot. It’s hard taking pictures where you don’t know anyone. Or at a show at a teen center where everyone is really young—that’s not right either. I’m not sure why people are so comfortable with me. I don’t spend a lot of time looking through the viewfinder or arranging a shot.

So did taking pictures at shows change how you interacted with people?

Yeah, it kept me in the scene. It’s a good way to meet people, and it gave me something to do. Now it seems pointless to go to a show without my camera, just a drink in my hand.

You must have amazing archives.

It’s almost like my photos are more important to individual people than to the scene. People say to me all the time, “You have documented my life.”

Did you ever accidentally capture something on film? Like in Blowup?

There’s the heroic beer truck robbery at Eastern Front.

When I see Glen Friedman or Bob Gruen’s work I think, “Where were you during the ’90s? Did you still take pictures, but only of lousy bands no one wants to see?”

Maybe they didn’t stick with the underground stuff very long.

Roberta Bayley did the same thing, Ed Colver…but you seem to have an enduring love for small, crappy bands?

All bands are better before they have an audience, before they are bound by them. Once the band gets bigger, the crowd gets diluted and the music gets watered down. Also the venues get bigger, and really annoying. They require special agreements to take pictures.

What would you like to see happen to your work?

I did a show in Oakland a few years back that was fun. The show was cool after it was done, but collecting all the pictures was a hassle. The digital age has spoiled me. I recently did two photos in a show at the San Jose Metro—the theme was on dive bars. And a book is in the back of my mind. It would be easier to do new stuff, but the old stuff is more interesting to the people who can afford a coffee table book. And it would be nice to see the pictures printed on really good paper. I think it is important to document the Bay Area. Other scenes have been documented pretty well.